American scientists are developing and testing a gene-modifying vaccine for the malaria-causing parasite, helping humans avoid infection from this disease when bitten by mosquitoes.

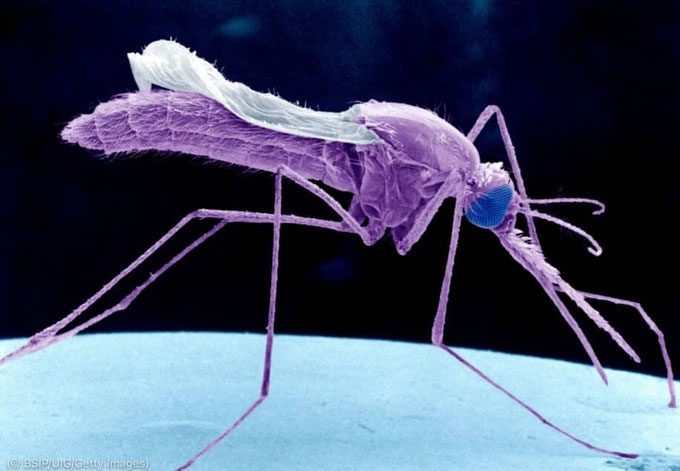

Malaria is one of the deadliest diseases today. It is transmitted through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes (the vectors for malaria).

The mosquitoes inject parasites from their saliva into the human bloodstream, causing fever, headaches, chills, and can even lead to coma and death if left untreated.

According to estimates by scientists based on a 2021 WHO report on this disease, approximately one person dies from malaria every 60 seconds.

Removing certain genes in the virus may help humans avoid malaria infection when bitten by mosquitoes. (Image: Getty).

Recognizing this danger, a team of scientists from the Seattle Children’s Research Institute in Washington and the U.S. National Institutes of Health has been researching an experimental vaccine called PfGAP3KO, which uses the CRISPR gene-editing system that acts like molecular scissors to cut out DNA segments that encode dysfunctional and disease-causing genes.

The Vaccine Induces Early Immune Response

The researchers believe that gene-modified malaria parasites represent a potential platform for creating a malaria vaccine by removing disease-causing genes from the virus.

When the vector (mosquito) transmits the disease-causing virus to humans, the parasite (Plasmodium falciparum) moves to the liver and multiplies there.

At this stage, the human host shows no symptoms; symptoms are only felt once the virus escapes from the liver and infects red blood cells.

Identifying the issue, the scientists have attempted to act before this stage, using CRISPR to cut out DNA encoding dysfunctional or disease-causing genes.

The research team has successfully removed three genes, including gene P52, P36, and SAP1 from the parasite. The results showed that the virus could not reproduce in the liver and invade the red blood cells.

Volunteers participated in the experiment by allowing mosquitoes carrying the modified virus to bite their arms to monitor the potential for malaria infection in these individuals (Image: NPR).

The researchers believe that this type of vaccine will provide better protection than vaccines based on single proteins, such as the RTS,S malaria vaccine approved by the World Health Organization in 2021, which has an efficacy rate of only 30-40%.

The PfGAP3KO vaccine could stimulate broader protective immune responses, and its duration of effectiveness may be longer.

Dr. Ashley Vaughan, from Washington University School of Medicine and a co-author of the study, concluded: “We hope to begin clinical trials with this new vaccination vaccine in 2023.”

According to the WHO’s 2021 report, an estimated 241 million cases of malaria occurred globally, with 627,000 deaths from the disease, an increase of 14 million cases and 69,000 deaths compared to the previous year.

Notably, pregnant women and children under five years old account for 80% of these deaths.

To date, malaria remains prevalent in 91 countries and territories. More than 1.3 billion people live in malaria-endemic areas.

In Vietnam, approximately 12 million people live in malaria-endemic regions, with the majority being poor and from ethnic minorities.

Particularly, our country lies in a tropical climate, creating favorable conditions for malaria vectors like mosquitoes, posing a risk of disease outbreaks.