In the 10th century, the concept of the world was unfamiliar and mysterious to most people.

Even the most powerful empires had limited knowledge of distant lands. Driven by a passion for geography and culture, Ibn Hawqal (?-after 978) set out to explore and validate life in areas deemed “uninhabitable,” ultimately sketching a map of the world.

The Adventurous Writer

Muhammad Abū’l-Qāsim Ibn Hawqal was born in the town of Nisibis, Upper Mesopotamia (present-day Nusaybin, Turkey), with the birth name Alī Ibn Hawqal al-Nasībī. Apart from his full name, historical records offer no insights into his childhood.

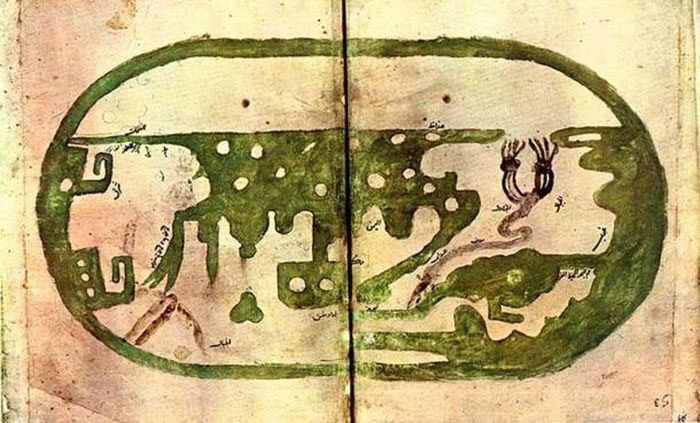

Ibn Hawqal’s primitive world map. (Image: Ancient-origins).

During Hawqal’s lifetime, both he and the various kingdoms and empires were largely ignorant of the surrounding world and lacked a global map. People could only speculate about other countries and strange cultures in far-off places without any understanding of the realities there. Even residents of the Eastern Roman Empire had little knowledge of the neighboring Scandinavian Peninsula.

In the 10th century, two Arab scholars, Istakhri (850 – 957) and Ahmed ibn Sahl al-Balkhi (850 – 934), dissatisfied with their limited knowledge, embarked on journeys to explore the world, aspiring to uncover every corner of the globe.

They traveled extensively, writing numerous Arabic texts about the lands they visited. It is likely that Hawqal was inspired by their writings. Around 943, he began his journey south of the equator along the East African coast.

Prior to Hawqal, some Greek writers who had never been to Africa speculated that it was a barren land unfit for habitation. Contrary to their beliefs, Hawqal witnessed thriving tribes. However, influenced by Islamic beliefs in an era of pagan discrimination, he dismissed the inhabitants of the African continent as “kafir” (infidels), barbaric, and uncivilized.

After leaving Africa, Hawqal crossed the Mediterranean, visiting Sicily and Al-Andalus (present-day Spain). He was particularly fond of these two places, as most of the inhabitants were also Muslim, before continuing to the “Islamic holy land” of Fraxinetum (present-day La Garde-Freinet, France).

Notably, Hawqal made an important trip to the “land of rum” – the Byzantine Empire, visiting the capital Constantinople, where he experienced and documented the multicultural life. He then ventured into the Caucasus region, verifying that approximately 360 different languages were spoken there, yet communication was possible due to the common language of Arabic.

Portrait of writer Ibn Hawqal (? – after 978). (Image: Ancient-origins).

The Face of the Earth

For 30 years, Hawqal tirelessly traveled, explored, and meticulously documented the geography and people of the places he visited. In the European steppes, he encountered the Bulgar and Khazar tribes.

In the Balkans, he interacted with the Slavs. In the Kingdom of Kievan Rus – a confederation of tribes in Eastern Europe, he experienced life in the capital city of Kiev. Following the Indus River, he discovered the Sindh people…

The further he traveled, the more lands and peoples he encountered. In every place he visited, he endeavored to map and record cultural and social life. By 969, after traversing Africa, Europe, and Asia, he compiled his sketches into the first world map, titled Sūrat al-‘Arḍ (The Face of the Earth).

Compared to today’s global maps, Hawqal’s The Face of the Earth is undoubtedly rudimentary; however, in the 10th century, it was the most complete and reliable world map available. Many caravans and seafarers relied on this map to navigate accurately to their destinations, thanks to Hawqal’s notes on languages and cultural life which allowed for proper preparations.

It is not an exaggeration to say that The Face of the Earth was a “revolutionary global map.” Hawqal’s extensive knowledge provided invaluable resources for travelers, merchants, and rulers across the globe during this time.

In addition to creating precise, detailed maps, Hawqal maximized his advantage as a writer. Thus, his map collection, The Face of the Earth, also served as a travelogue, recounting his global journeys. With a humorous writing style and exaggerated storytelling, Hawqal captivated readers with his tales and adventures.

In the chapter about Al-Andalus, he describes the fertile agricultural region of Fraxinetum, highlighting innovations made by Muslim farmers and fishermen. In the chapter on the Byzantine Empire, he narrates the astonishing multicultural and multilingual life there. In the chapter about Kiev, he astonishes readers with the trade routes of the Volga Bulgars and Khazars…

The more one reads The Face of the Earth, the more one is drawn into the spirit of adventure. After Hawqal’s passing, many writers and explorers followed in his footsteps, traveling, discovering, and adding to the body of knowledge.

For many centuries afterward, Hawqal’s travelogue and map collection remained a guiding light for many. In the 1870s, it was edited and published by the famous Dutch Orientalist Michael Jan de Goeje (1836 – 1909).

Today, The Face of the Earth continues to serve as a valuable geographical and literary resource. It showcases a passion for knowledge, inspires learning, and opens a window into the medieval perspective of the world.