Tie-dye is a dyeing technique that involves tying sections of fabric to prevent those areas from absorbing color. This method creates a spontaneous effect for the colors displayed on the fabric’s surface.

Various tie-dye techniques and styles have different origins around the world, from Peru to Nigeria, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

Each culture has found unique ways to add to their designs, including tying fabric to sticks, creating patterns with wax, or using rice, stones, or beads to create knots. However, throughout history, tie-dye has been reserved for specific purposes, often reflecting an individual’s status, role, and beliefs.

It is impossible to pinpoint which culture developed tie-dye first and when. Mr. Lee Talbot, curator at the George Washington University Museum and the Textile Museum (USA), states that this is evidenced by the “perfection” in the earliest remaining patterns found.

Experts in textile history agree on the cultural significance behind various tie-dye methods around the world and how they have persisted into modern times.

Bandhani in India

Bandhani is the oldest known form of tie-dye, dating back to 4000 BC in the Indus Valley Civilization, located in what is now northern India. This method is still practiced in India today.

Bandhani patterns are created by tying small bundles of fabric with thread before dyeing. This series of small bundles allows the underlying fabric to remain unaffected by the dye, forming swirls and patterns on garments such as saris (a popular attire for Indian women), scarves, and turbans.

According to Assistant Professor Natalie Nudell from the Fashion Institute of Technology (USA), modern bandana patterns used in the West have developed from bandhani.

Some of the earliest descriptions of bandhani are preserved in records and paintings at the Ajanta Caves in Central India. In northern India, bandhani-dyed fabrics are referenced in songs and poetry as symbols of love.

Mr. Talbot notes that the connection between bandhani-dyed fabric and love persists in India today—bandhani fabric is often used as gifts in weddings.

Amarra in Peru

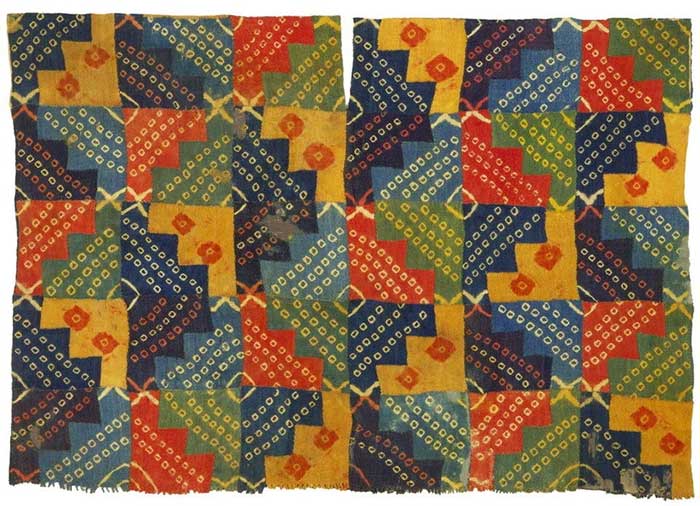

Amarra emerged around 1500 years ago in Peru. This tie-dye form spread across the Americas to as far as the Southwest. Here, some of the earliest amarra-dyed fabrics created by the Pueblo ancestors have been discovered, dating back to the 10th century.

According to scholar Laurie Webster from the University of Arizona (USA), a distinctive feature of amarra is the diamond-shaped grid design with dots in the center, a pattern symbolizing snake skin or cornfields.

Ms. Webster states that these patterns are sacred to indigenous groups in the Americas. They have used this tie-dye technique to create designs on clothing, blankets, and other decorative textiles.

Additionally, Ms. Webster notes that in the remaining murals and other images, deities and religious figures are often depicted wearing amarra-dyed items.

The ancient Wari people of Peru were masters of the amarra technique. (Image: Textile Museum (USA)).

Bandhani-dyed fabric in India. (Image: Adair Group).

Shibori in East Asia

Although the shibori dyeing technique originated in China, it is best known as an art form in Japan for over 1,000 years. The earliest shibori patterns remaining in China date back to the 4th century. This method is still practiced here, particularly by minority groups in Southwest China.

For a shibori dyeing method, artisans place a grain of rice or a small metal piece into each fabric bundle and tie it tightly with thread. After dyeing the fabric, the threads are removed, creating small circles. This tying, dyeing, and untying process takes considerable time to produce intricate patterns.

According to Ms. Nudell, this is an extremely time-consuming and labor-intensive technique that is highly valued in Japan. She believes that farmers used indigo to create shibori patterns on clothing made from hemp fibers. Shibori-dyed silk kimonos are very expensive, and mostly only the upper class can afford them.

Shibori-dyed fabric became popular among nobility, wealthy merchants, and even high-class courtesans. As shibori became a symbol of luxury, the government of the time completely banned it as part of Japan’s luxury laws.

This law dictated how each social class could dress and spend their money. The authorities viewed this as a moral responsibility to maintain the hierarchy. A special edict passed in the late 17th century stated that no one was allowed to make shibori.

However, shibori remained popular even during the ban. The prohibition on shibori was lifted in 1868, and it continues to be a popular traditional practice for kimonos in Japan today.

Adire in Nigeria

In Nigeria, the Yoruba people apply the adire dyeing technique by folding the fabric before tying it with thread or banana leaf fibers and dyeing it. Similar to shibori, the fabrics are often dyed blue using indigo plants.

They also create circular patterns by wrapping stones and large beads inside the fabric, akin to shibori.

For the Yoruba, Ms. Nudell explains that the admired designs on clothing are closely tied to an individual’s identity. Adire often carries symbols of the wearer’s social and cultural status—such as their age or rank in society.

A fabric traditionally dyed by Nigerians. (Image: AP).

“Each culture expresses tie-dye in a slightly different way and interprets it according to their own aesthetics,” Mr. Talbot says.

Adire continues to hold significant economic and social roles for the people of Nigeria, as creating clothing, bedding, and decorative items provides job opportunities for local farmers, weavers, and dyers. According to Mr. Talbot, globally, for centuries, something about tie-dye has captured cultural attention.