Egypt is home to the Giza Pyramids, while Iraq boasts the Ziggurat of Ur – an exceptionally well-preserved technical achievement that has outlasted the ruins of an important ancient city.

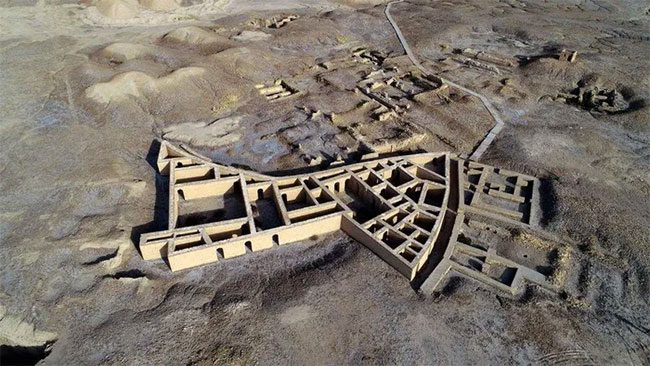

About 4,000 years ago, the barren, pale lands of this Iraqi desert were the center of a thriving civilization. Today, the remnants of the great city of Ur, which once served as the administrative capital of Mesopotamia, lie within a desolate wasteland near one of Iraq’s most notorious prisons.

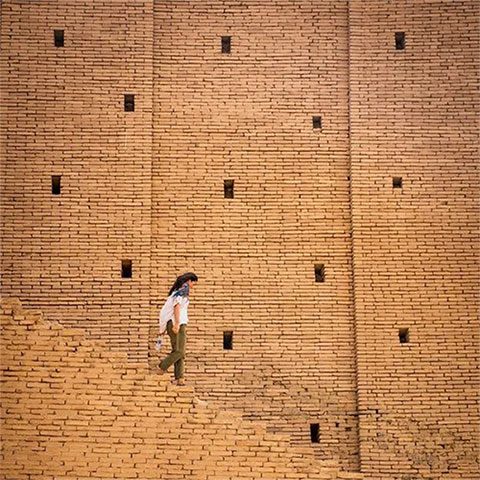

In the shadows of the towering prison walls, Abo Ashraf, who claims to be the caretaker of the archaeological site, along with a handful of tourists, is the only sign of life for miles around. At the end of a long wooden walkway, an impressive ziggurat stands as nearly the sole remnant of the ancient Sumerian metropolis.

Ziggurat of Ur in Iraq. (Photo: BBC).

Ziggurat of Ur – An Ancient Sumerian City

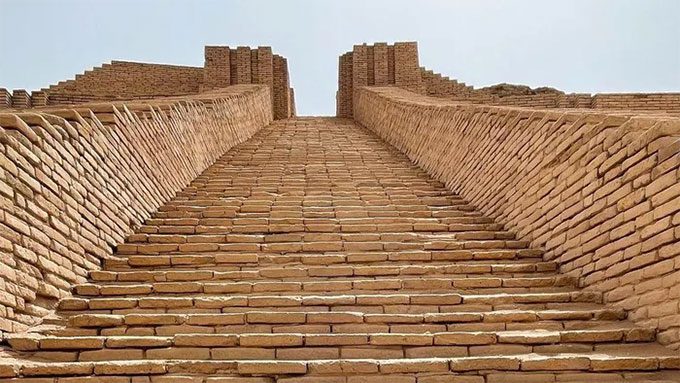

The Ziggurat of Ur, a colossal structure over 4,100 years old, features multiple tiers and grand staircases. A high chain-link fence blocks the entrance, and a stone-paved parking lot is the only hint of the modern world.

The earliest ziggurats predate the Egyptian pyramids, with several monuments still visible in present-day Iraq and Iran. They are as majestic as their Egyptian counterparts and served religious purposes, yet they differ in several ways: ziggurats have steps contrasting with the flat walls of pyramids, they lack internal chambers, and they feature temples at the top instead of burial chambers within.

Maddalena Rumor, an expert in Ancient Near Eastern studies at Case Western Reserve University in the U.S., states: “A ziggurat is a sacred building, essentially a temple on a stepped platform. The earliest temples show simple one-room structures on a small platform. Over time, these temples and platforms were repeatedly reconstructed and expanded, becoming increasingly complex and larger, reaching their most perfect form in the Ziggurat.”

The Ziggurat of Ur was constructed slightly later (about 680 years after the first pyramid), but it is renowned for being one of the best-preserved structures, also due to its significant location in Ur, which holds a prominent place in history.

Accordingly, Mesopotamia is the birthplace of artificial irrigation: the people of Ur dug canals and ditches to regulate water flow and irrigate lands further from the Euphrates River.

The Sumerians carved hundreds of square holes in the outer walls to allow the inner mudbrick core to stay dry. (Source: Geena Truman).

Structure of the Ziggurat of Ur

The lower tiers of the structure still remain today, although the temple and terraces at the top have been lost. To visualize what they looked like, experts have employed various technologies and ancient texts (from historians like Herodotus, as well as the Bible).

In a 2016 paper titled “A Ziggurat and the Moon,” Amelia Sparavigna, an archaeological imaging specialist at the Polytechnic University of Turin, wrote, “A ziggurat is a pyramidal structure with a flat top, with a core made of sun-baked bricks, covered by fired bricks. The exterior surfaces were often glazed in different colors.”

Based on the remnants found at the site, it is widely agreed that the Ziggurat of Ur is a temple made of ceramic tiles situated atop two gigantic tiers of mud bricks. The base alone comprises over 720,000 meticulously stacked mud bricks, each weighing up to 15 kilograms.

Reflecting the Sumerians’ knowledge of lunar and solar cycles, each of the four corners of the ziggurat is aligned precisely with cardinal directions, and a grand staircase leading to the upper tiers is oriented towards the rising sun during the summer solstice.

Each corner of the ziggurat points toward a cardinal direction, and a grand staircase leads towards the rising sun during the summer solstice. (Source: Geena Truman).

King Ur-Nammu laid the first brick of the ziggurat around 2100 BC, and the construction was completed by his son, King Shulgi, during a time when the city was the thriving capital of Mesopotamia.

However, by the 6th century BC, the ziggurat faced devastation due to the harsh desert heat and sand. King Nabonidus of Babylonia began restoring the ziggurat around 550 BC, but instead of recreating the original three tiers, he built seven tiers, aligning with other grand structures of Babylon at that time, such as the Etemenanki ziggurat, which some believe to be the Tower of Babel.

Much of the ziggurat remains intact today, largely due to three brilliant innovations by the original Sumerian engineers.

- The first was ventilation. Like other ziggurats, this structure was built with a core of mud bricks surrounded by sun-baked bricks. Because the core retained moisture that could lead to overall degradation of the structure, the Sumerians drilled hundreds of square holes into the outer walls to allow for rapid moisture escape. Rumor has it that without this detail, “the mudbrick interior could soften during heavy rains, ultimately swelling or collapsing.”

- The second was that the walls were constructed at a slight angle. This allowed water to flow down the sides of the ziggurat, preventing accumulation on the upper tiers; the angle also made the structure appear larger from a distance, intimidating the empire’s enemies.

- Finally, the temple at the top was built entirely of fired bricks bound together with bitumen. This natural tar prevented water from seeping into the unbaked core.

Despite these achievements, by the 6th century AD, the once-thriving city had become materially depleted. The Euphrates River had shifted its course, leaving the city without water and thus uninhabitable. Ur and the ziggurat were abandoned and subsequently buried under a mound of sand by the winds and the passage of time.

Ur is believed to be the birthplace of Abraham in the Bible and the home of the first laws. (Source: Assad Niazi / Getty Images).

The upper stairs and the colorful temple have long been destroyed and lost to time. Yet across the vast, nearly flat desert, small mounds can be seen scattered throughout the area, waiting to be excavated, surely hiding a world of untapped treasures.