Clearly, a chariot needs a horse to pull it. Is there a type of horse small enough to gallop inside our bloodstream?

If you’ve ever played the game “Age of Empires,” known as Đế chế in Vietnam, you’re likely familiar with the “Scythe Chariot,” a military unit inspired by the historical war chariots.

With their compact size and nimble maneuverability, these two-horse chariots can reach speeds of 72 km/h on flat ground, corner almost unchangingly, and conquer various terrains, including battlefields.

Throughout a history spanning 6,500 years—since the invention of the wheel and the domestication of horses—these chariots have represented the fastest and most efficient mode of transport our ancestors could devise, right up until the pre-industrial era.

If not for the three Industrial Revolutions that occurred consecutively over the past 300 years, chariots might still dominate every road on Earth. Fortunately (?), the advent of steam engines, internal combustion engines, and more recently, electric motors, has relegated these chariots to ancient games or left them to exist only in film sets and museums.

However, a group of scientists at the University of Tokyo is looking back into the past to learn from these thousands-of-years-old chariots. They have recently created a “microscopic chariot,” measuring only one-third the width of a human hair.

These chariots may one day fulfill the dream of the renowned theoretical physicist Richard Feynman in 1959, who first proposed the idea of a tiny machine that could operate within the human body.

These chariots can potentially navigate into the stomach, weave through blood vessels, help us clear fat, break down blood clots, transport dead cells, or deliver cancer medication precisely where tumors are developing.

But why not use a car, submarine, or tiny robot to accomplish this? Why resort to a chariot—a primitive and seemingly outdated vehicle?

And there’s an even more intriguing question:

While nano 3D printing and etching technology has enabled engineers to create vehicles small enough to navigate human blood vessels, how do we shrink horses down to micrometer sizes to pull these chariots within our bloodstream?

Clearly, a chariot must have a horse to pull it. Is there a “horse” small enough to gallop right inside our veins?

1. Japanese engineers have created the world’s smallest “chariot.” It resembles a Scythe Chariot unit from the AoE game

Just as all roads lead to Rome, the dream of tiny chariots operating within the human body has a common origin: the presentation of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Richard Feynman in 1965.

Dressed in a pink polo shirt tucked into brown pants and beige shorts, Feynman stood in the auditorium at Caltech that year to share his vision of a world where people could manipulate atoms to assemble tiny machines capable of diving deep inside their own bodies.

The presentation titled: “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom: A Proposal for a New Field of Physics,” ultimately opened the door to over four decades of remarkable developments in nanotechnology.

During this time, humans have created microscopes with magnifications of up to 50 million times, enabling them to see every “space down there,” beneath the scale between atoms.

The next step was to find methods to fabricate tiny machines.

Unfortunately, assembling these machines, as Feynman envisioned, was not easy. It wasn’t until about a decade ago that scientists began to achieve this.

For example, in 2018, a team of researchers at the University of California created gold nano robots that could be propelled by ultrasound and crawl within human blood vessels.

In 2020, a research group from Leiden University in the Netherlands used micro 3D printing to create the smallest tugboat model in the world, measuring just 30 micrometers.

Although the boat was merely a static model without the capability to move, in 2023, a group of engineers at the University of Colorado developed a structure that could open a new future for it.

This was a propeller measuring just 20 micrometers, capable of spinning to generate propulsion under the influence of ultrasound. Thus, you can start imagining a super tiny Benchy boat equipped with a propeller motor.

However, for such mechanical machines to swim in human blood, they still face numerous challenges.

2. Energy, propulsion systems, and the viscosity of blood

The first challenge for a microscopic robot running in human blood is the environment of blood itself, a non-Newtonian fluid.

Imagine stirring a stick in a bowl of water; no matter how hard you stir, the viscosity of the water remains unchanged. Therefore, the resistance at the tip of your stick is always a constant, allowing you to stir the water bowl easily.

However, if you add flour to that bowl of water to make dough, things change. The flour mixed with the water creates a non-Newtonian liquid; the more you stir, the greater the viscosity of the mixture becomes, and consequently, the resistance increases.

The result is that the stick will get stuck while stirring.

This is characteristic of non-Newtonian fluids like honey, tree sap, molasses, and human blood. Therefore, if a Benchy boat is to swim in human blood, it must have a propeller strong enough to overcome the viscosity of blood.

This leads to another paradox between size and energy.

Suppose scientists want to create an electrically powered Benchy boat within human blood; to achieve greater propulsion, they would need to install a larger battery on it.

This contradicts the requirement for their size to continuously decrease. The smallest self-powered robots today are often not small enough to navigate human blood vessels.

For example, Pillcam is a robot used as an endoscopic device, measuring about the size of a capsule. It can be swallowed, travel into the stomach, and capture images of the entire human digestive tract from the stomach until it is expelled through the rectum.

The journey lasts from 8 to 12 hours, requiring Pillcam to have a sufficiently large battery to operate throughout that time. It needs enough power to maintain a capture speed of 2-6 images per second. On average, each journey of Pillcam through the human digestive tract allows doctors to collect 50,000 images.

To this day, battery technology has not yet allowed engineers to design any robot smaller than 1mm that can operate effectively on self-generated power. Any battery smaller than 1mm would have significantly reduced capacity.

The limitations of battery technology have forced scientists to pivot towards a different direction in developing mini robots. They must separate the power source from the robot and turn to wireless energy sources.

A new generation of tiny robots has emerged from this. The idea is to drop antenna-equipped robots into the human body. Then, energy can be transmitted to them through laser light, ultrasound, or magnetic fields.

While this has helped reduce the size of robots below the micrometer threshold, if scientists want to wirelessly transmit energy to these robots, they still need to design them with a sufficiently large antenna to receive adequate energy.

Furthermore, the robots must be relatively close to the energy source to ensure efficient transmission.

Ultimately, the paradox between size and battery capacity merely transforms into a paradox between size, antennas, and distance. This is where the scientists from the University of Tokyo’s ideas come into play as they seek to…

3. Bringing “Chariots” Back to the Microscopic World

The first chariots on Earth were invented around the end of the second millennium BC. It is not surprising that they dominated roads across the globe for the next 4,000 years.

Chariots are the culmination of three of the greatest inventions in human history: the wheel, the ability to domesticate animals, and material fabrication skills.

The earliest archaeological evidence of these chariots was found in the graves of the Sintashta culture in present-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dating back approximately 2,000 years.

In the following 800 years, chariots appeared in almost all ancient civilizations across Central Asia, Europe, Egypt, China, and India. They served not only as a means of transportation but also facilitated trade, communication, and military purposes.

For over 4,000 years, chariots were considered the king of vehicles until the 19th century, when they began to be replaced by motorized vehicles powered by steam engines, fossil fuels, and now electric motors.

However, in some remote areas with limited fuel sources, animal-drawn chariots are still being used for transportation and production purposes.

The human body, lacking gas stations and electric vehicle charging stations, has also proven to be an ideal area to bring “chariots” back.

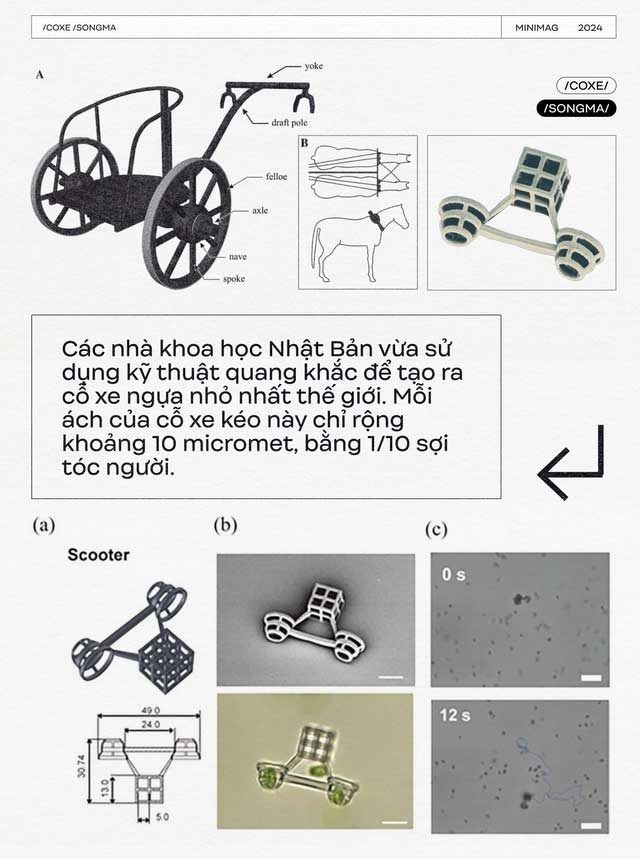

In a study published in the journal Small, scientists from the University of Tokyo, Japan, utilized two-photon coincidence lithography—a technique used to create the world’s smallest Benchy boat—to develop the world’s smallest chariot.

This chariot features two yokes—devices used to harness animals for pulling—and a compartment simulating the structure of ancient chariots.

However, at a size of only about 10 micrometers, this chariot certainly cannot use horse power. Nonetheless, scientists found a suitable organism to pull it: Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (CR).

The Chlamydomonas reinhardtii algae can be trapped in the conical yokes of this smallest chariot. It then uses its flagella to pull the chariot along.

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii are single-celled organisms, approximately 10 micrometers in size, living in freshwater and possessing flagella. These flagella function like frog swimming motions, enabling the algae to swim at speeds of 100-200 micrometers/second, which is 10-20 times their body length.

In relative terms, these algae cells swim even faster than human F1 cars. Each F1 car, measuring 5 meters long, travels at speeds of 300 km/h, equivalent to only 83.3 m/s, which is 16.67 times the length of the car.

By trapping two Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells in two conical yokes, scientists have effectively created a “bacterial chariot” capable of linear motion, turning, reversing, and even flipping in fluid.

“You may have heard the term horsepower, but have you ever heard of algae power?

Just like a sled pulled by a pack of dogs or a plow pulled by oxen, researchers have created tiny machines that can be pulled by these tiny, vibrant algae cells,” stated the University of Tokyo’s website.

4. A New Direction for the Microbot Field

In fact, this is not the first time scientists have thought of using the biological energy of microorganisms to generate kinetic energy for tiny robotic machines.

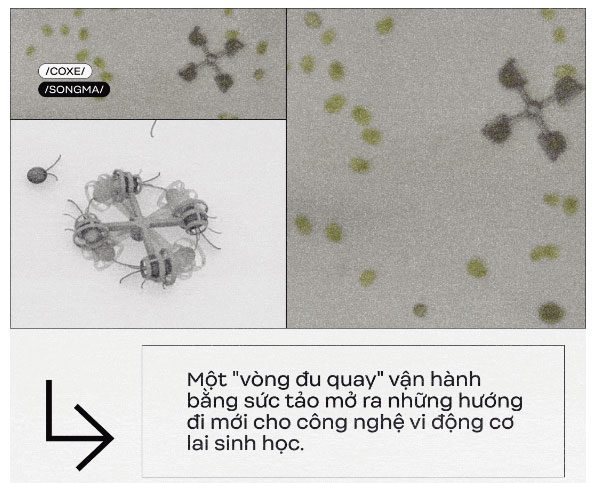

In 2017, a research team at the University of Rome, Italy, also trapped E. coli bacteria with flagella to rotate a 7.6 micrometer gear at a speed of 20 revolutions per minute.

This gear was made from 15 micro-chambers, each capable of housing an E. coli bacterium that extends its flagella to collectively push the gear in one direction.

In the new study, scientists at the University of Tokyo have also managed to create a similar micro-motor using the propulsion of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii.

With a size five times larger, they only needed four algae cells to rotate a “carousel” with four axes at approximately 16 revolutions per minute. By increasing the number of axes and algae cells, this carousel could spin faster and provide a strong propulsion mechanism for hybrid microbots.

This reality demonstrates that “algae power” can be harnessed in many creative directions, allowing engineers to create not only rudimentary vehicles but also assemble complex mechanical structures, such as hybrid propulsion engines.

“Microorganisms possess incredible mobility, making them potential candidates to provide thrust for ultra-small machines”, the researchers wrote.

The advantage of these engines is that they do not depend on external power sources. The activity of the algae can also be controlled by light or nutrients. For example, by simply injecting a nutrient or increasing light intensity, you can lure these algal chariots to move towards the desired location.

It is evident that these “algal-powered chariots” are once again bringing us closer to Richard Feynman’s dream, through a completely new approach.

While the microscopic world witnesses the failure of conventional human engines, opportunities are arising for more primitive yet more efficient vehicle structures.

With two Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells attached to a push cart, one day we may witness these vehicles operating in freshwater lakes, monitoring the environment, collecting pollutants, or distributing nutrients.

If a micro-engine system using Chlamydomonas reinhardtii can be developed that is protected from the immune system, they could also provide kinetic energy for machines operating inside the human body, delivering medication to the exact location of tumors, clearing cholesterol from blood vessels, or breaking down clots that cause blockages.

Perhaps, even in the microscopic world, human vehicles need to undergo gradual evolutionary steps. There, the chariots of the Bronze Age could be brought back before we witness an industrial revolution on a micrometer scale.

For instance, a revolution that shrinks battery cells, lithographically resolving to the atomic level, creating ultra-small electric motors for the tiny robots imagined by Richard Feynman.

Do not forget that humanity had to ride chariots for 4,500 years before achieving automobiles in the last 300 years. We may wait, contentedly, for these “algal chariots.”

For when it comes to the microscopic world, there are still “plenty of gaps down there.”