The Frozen Zoo in San Diego is managed by just 4 researchers overseeing more than 11,000 specimens representing 1,300 different species and subspecies.

In a laboratory located in the basement of a wildlife park spanning 728.4 hectares in San Diego, California, Marlys Houck looks up at a man in uniform holding a blue insulated bag containing eye parts, trachea, feet, and fur. The bag contains small soft tissue samples collected from animals that have died naturally at the zoo.

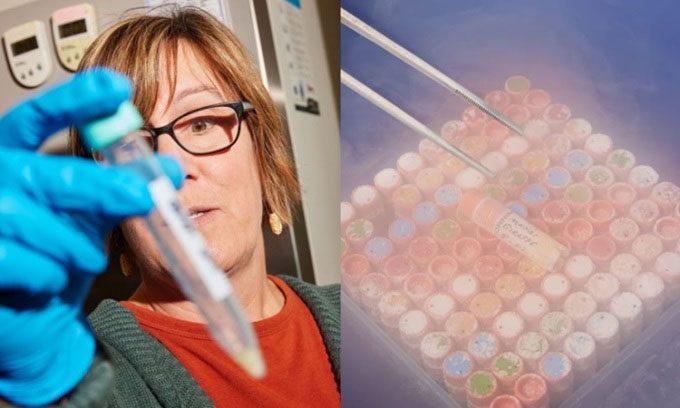

Research coordinator Ann Misuraca retrieves a cell container from the incubator for microscopic examination at the Frozen Zoo. Photo: Maggie Shannon

The man holding the bag is volunteer James Boggeln. He hands it to Houck, the manager of the lab known as the Frozen Zoo. She and her colleagues will begin the process of placing the tissue samples into a research and conservation bank for the future. They place the tissue in a conical flask for enzymatic digestion, after which lab staff slowly incubate them for a month, cultivating a large number of cells that can be frozen and reactivated for later use, according to the Guardian.

With nearly 50 years of history, the Frozen Zoo contains the world’s largest and most diverse collection of living cell cultures, with over 11,000 specimens representing 1,300 species and subspecies, including 3 extinct species and many endangered ones. Today, the Frozen Zoo is managed by a team of 4 female staff members. They supervise a vast collection of labeled test tubes such as “giraffe,” “rhino,” and “tortoise,” all stored in a large round tank filled with liquid nitrogen. In a world impacted by climate crisis and biodiversity loss, freezing species provides a means of conservation for the future.

The work here is significant, but the accelerating extinction crisis puts pressure on Houck and her colleagues. It is a race against time to get specimens into the Frozen Zoo before the species vanish from the outside world. The job requires meticulous attention to detail as all specimens from birds, mammals, amphibians, and fish require different handling processes. Houck feels the pressure in her role, especially after a technical incident during her predecessor’s tenure resulted in the loss of 300 specimens, a year’s worth of work. Therefore, Houck dedicates all her focus to ensuring the safety of the frozen specimens in the zoo.

Manager Marlys Houck and Misuraca retrieve specimens from the nitrogen tank. (Photo: Maggie Shannon)

The zoo was established by a German-American pathologist named Kurt Benirschke in 1972. Benirschke began collecting animal skin specimens in a laboratory at the University of California, San Diego, and later moved to the San Diego Zoo after a few years. At that time, there was no technology for utilizing such specimens beyond basic chromosome research.

In the Frozen Zoo, Houck retrieves test tubes from the liquid nitrogen tank. These storage tanks are maintained at -196 degrees Celsius, a temperature that prevents cells from moving or changing, keeping them in a suspended animation state. At this temperature, cells can be revived and continue to live after decades or even centuries.

No two species are exactly alike; some groups of animals are harder to preserve than others. The Frozen Zoo started with mammals and then expanded to birds, reptiles, and amphibians. The success rate for mammals is up to 99%, according to Houck. For amphibians, the success rate is between 20% and 25%. Each rack in the liquid nitrogen tank holds 100 test tubes, with each tube containing 1 to 3 million living cells. These cells can provide viable solutions to many current and future issues.

Ultimately, the cells could be used to bring back completely extinct species, but that is not the primary goal. Instead, the material is used to save species that are struggling to survive today. In 2020, the Frozen Zoo used preserved frozen DNA to clone a black-footed ferret, the first endangered species in the U.S. to be cloned. Last year, frozen cells preserved for 42 years were used to clone two critically endangered Przewalski’s horses, providing valuable genetic diversity to the existing horse population to enhance resistance to new diseases and environmental threats.

The work at the Frozen Zoo in San Diego is part of a global effort to preserve everything from animals to seeds. Today, there are dozens of frozen banks around the world, primarily located in North America and Europe. The work in the San Diego laboratory is particularly groundbreaking, according to Sue Walker, the scientific director at Chester Zoo. She states that within a few decades, researchers will transform living cells into pluripotent stem cells, which can be reprogrammed to produce eggs and sperm.

Obtaining permits for animal tissue collection in many countries is quite challenging, so researchers hope to increase local collection output, especially near conservation centers in Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia. The research team adds approximately 250-300 specimens to the zoo each year. The nitrogen storage tanks are full, but the tanks are not at full capacity, so lab members continue to culture and store cells, which will determine the survival of endangered animals in the future.