While whales are indeed mammals and not fish, the title of the largest fish species on the planet currently belongs to the whale shark (Rhincodon typus). These creatures can grow up to 16 meters long and weigh over 20 tons, roughly the size of a double-decker bus.

Yet, during their journeys through the ocean, specifically while swimming beneath the surface, whale sharks frequently encounter accidents. Ironically, in these incidents, they are often the victims, colliding with vessels, suffering injuries, and even facing death.

The culprits are none other than the massive cargo ships operated by humans.

Whale sharks often encounter accidents when colliding with cargo ships.

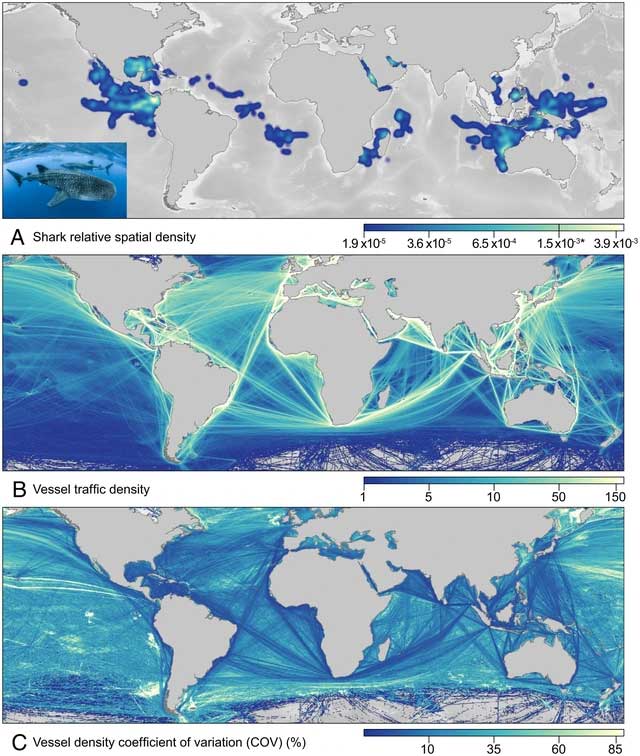

A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on May 9 revealed that up to 90% of the current migratory routes of whale sharks intersect with human high-speed maritime transport routes.

As whale sharks typically swim close to the water’s surface, they are vulnerable to being struck by enormous container ships. A collision with a vessel weighing over 300 tons can be fatal for a whale shark.

Scientists indicate that these traffic accidents have led to a decline of up to half the global whale shark population over the past 75 years. This has pushed the largest fish species on Earth onto the list of the most endangered shark species in the world.

This is the most endangered shark species in the world.

Human vessels are ravaging ocean routes

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), global trade currently relies on key maritime routes. Up to 90% of international goods are transported by sea, on ships carrying thousands of massive containers.

The advantage of maritime transport is that producers can ship large volumes at low costs, while logistics companies can consolidate shipments to reduce expenses. Containers can then be further transported by land once the oceanic voyages conclude.

Unfortunately, what benefits humanity often harms nature and wildlife.

An injured whale shark after a vessel collision.

The maritime routes of humans often connect distant ports on opposite sides of vast oceans. These routes are referred to as maritime highways and have a high incidence of intersecting with the migratory paths of many fish species.

Whales and whale sharks are often the targets of human cargo vessels when they spend extended periods swimming near the surface to feed on plankton. If a whale shark is struck by a large ship, the chances of survival are extremely low.

Accidents often go unreported because whale sharks are a species with negative buoyancy. This means that when severely injured and unable to swim, they will automatically sink to the ocean floor and die silently there.

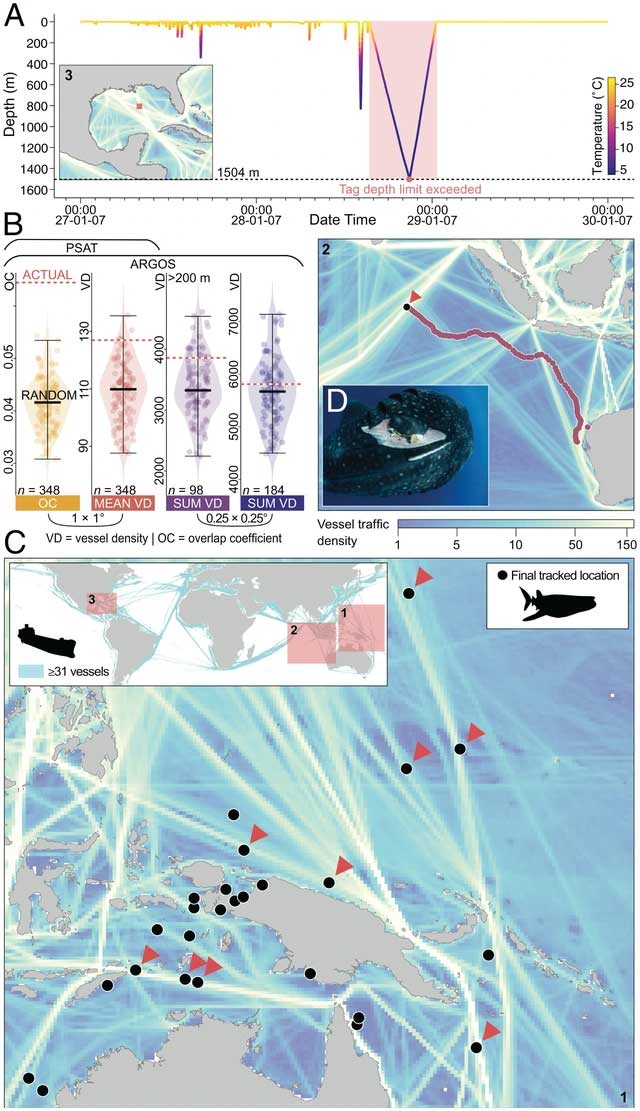

In their recent study, marine ecologists at the University of Southampton sought to attach tracking tags to 350 whale sharks to monitor their journeys and map their locations using satellites.

A whale shark fitted with a tracking tag.

These maps were cross-referenced with GPS systems tracking maritime routes, which included all waiting cargo ships, oil tankers, cruise ships, and fishing vessels weighing over 300 tons – capable of killing a whale shark upon collision.

“Our new research has found that this threat may be the leading cause of mortality for the world’s largest fish, the whale shark, more than any previously recorded cause,” said marine ecologist Professor David Sims.

“Unlike most other shark species that roam the open ocean, targeted or incidental fishing by industrial fleets is not considered the primary cause of the decline in whale shark populations. Instead, for this marine species, several factors indicate that human transport activities pose the greatest threat.”

92% of whale shark habitats are intersected by human shipping routes

This is the result of the first analysis of satellite data showing the extent of overlap between maritime transport routes and whale shark habitats. Scientists noted that areas like the Gulf of Mexico, the Arabian Gulf, and the Red Sea – where the densest ports and busiest shipping routes in the world are located – are also where whale sharks frequently encounter vessels.

Map of human shipping routes overlapping whale shark habitats.

GPS data shows that whale sharks often cross maritime transport routes and collide with ships that are dozens of times larger and faster than they are. This leaves the sharks with very little time to react to an approaching vessel.

Researchers observed that 24% of GPS signals from tagged whale sharks disappeared as they crossed a shipping route. Even accounting for random technical errors of the transmitters, they believe this percentage indicates that whale sharks have been struck by vessels and sunk to the ocean floor.

Some devices attached to whale sharks recorded their last known positions near that of a cargo ship, while their depths continuously decreased to hundreds of meters below the ocean surface.

This provides direct evidence of a collision with a vessel that resulted in the death of a whale shark.

Locations where whale shark GPS signals ended coincide with human shipping routes.

Professor David Sims stated that there are currently no international conventions in place to protect whale sharks from such vessel collisions. Many ships are too large to even notice they have struck a shark.

Therefore, he emphasized that to protect the largest fish species on the planet, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) needs to establish a reporting channel for collisions between vessels and whale sharks. This would enable them to document accidents and create a map of areas with the highest likelihood of whale shark encounters.

Subsequently, the IMO could implement regulations requiring vessels to reduce speed or navigate more cautiously in areas where whale sharks are present. Professor Sims indicated he is willing to provide maps of these areas to test such regulations.

“Taking action now is the only way to prevent the whale shark population from declining further and facing the risk of extinction,” he stated. “It saddens me to witness the deaths of this magnificent creature occurring right along human shipping routes, for which we currently have no measures to prevent these accidents.“