The early 1900s marked the age of coal and iron. The industrial landscape was noisy and grimy, with smoke from coal burning permeating everywhere. However, few people were aware of a surprising reality: this was also the nascent period for exploiting solar energy.

At that time, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was one of the industrial centers on the East Coast of the United States. But things here had exceeded tolerance levels. In 1904, city officials created specific regulations aimed at making the air cleaner. These regulations limited the amount of smoke emitted from chimneys and open spaces, imposing financial penalties on those who exceeded the allowable smoke levels. However, it wasn’t until half a century later, in 1955, that the United States implemented the Air Pollution Control Act.

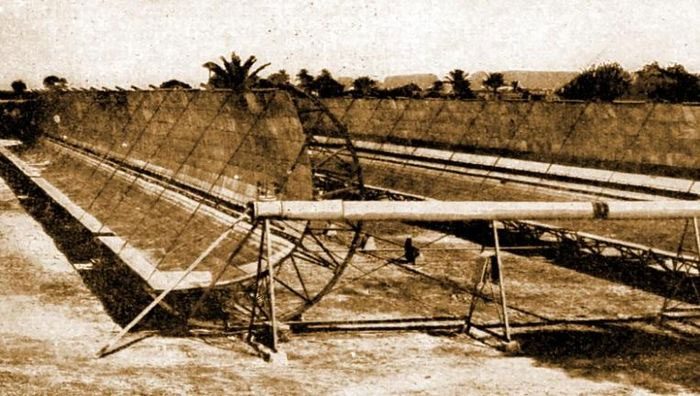

Frank Shuman’s invention tested in Egypt in 1913. (Image: BBC).

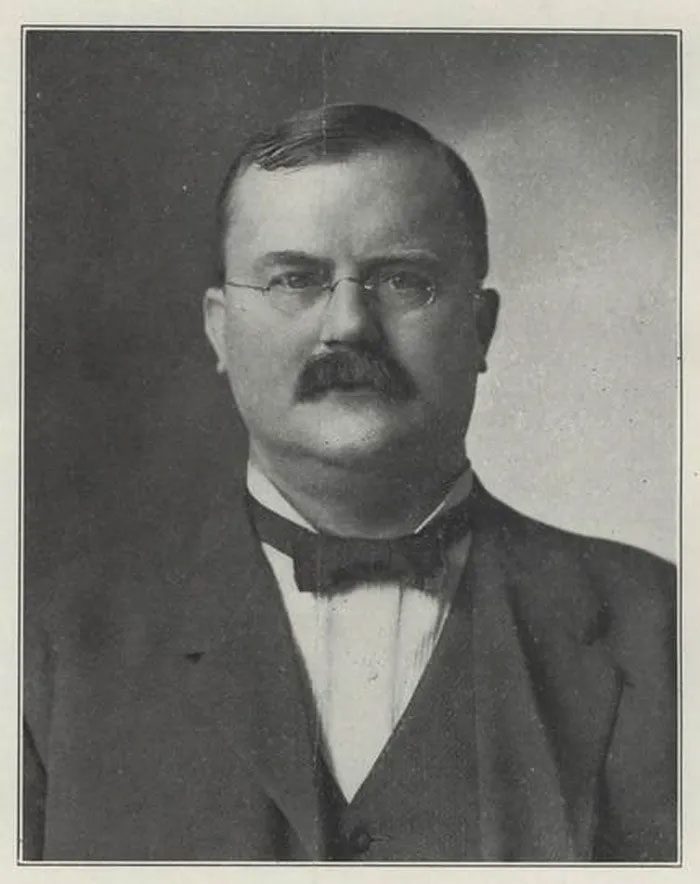

At that time, American inventor Frank Shuman was interested in clean energy, particularly in harnessing the sun’s heat to power machinery. It took over a century for ideas like his to gain significant traction, but his work was a turning point and is considered the “first seed” in harnessing solar power.

In the 1890s, Shuman invented a method for reinforcing glass with internal wires. This glass was more fire-resistant and remained intact when cracked, making it less likely to produce sharp, dangerous shards.

Shuman began his career in Virginia before moving to work for his uncle’s metal manufacturing plant in Philadelphia. The plant was casting a statue of Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn, and used electrolysis to coat the statue’s surface with a thin layer of aluminum to protect it from the polluted air surrounding City Hall.

Journalist Christopher R. Dougherty wrote on the Philadelphia website Hidden City that within two weeks in 1892, Scientific American published articles about the glass reinforcement methods and the aluminum coating for the statue. These articles were successful enough that Shuman decided to quit his job and focus full-time on his inventions.

As a veteran inventor, Shuman had long been fascinated by the concept of using natural forces to generate electricity. Christopher R. Dougherty noted: “Our riverbanks have many coal fields, oil refineries, and cheap fossil fuels, so for Shuman, imagining the end of these resources was ahead of his time.“

In 1906, Shuman began research at a complex he built at his home in the Northeast suburb of Tacony, Philadelphia, to create a solar-powered engine. Reflective panels were placed around an insulated box designed to pivot to follow the direction of the sun.

The sunlight was directed into a vacuum-sealed water container to lower its boiling point. This container was connected to a low-pressure steam engine. In 1913, Shuman traveled to Egypt to showcase his technology.

While Shuman was working on his “solar engine”, another American inventor, Aubrey Eneas, created a giant solar-powered metal engine with nearly 1,800 mirrors for an ostrich farm in California in 1906. This device worked and powered a pump to irrigate land. However, it was too expensive and cumbersome to be practical.

American inventor Frank Shuman. (Image: BBC).

News of Shuman’s projects reached Egypt, which was then under British military occupation. Egypt had vast cotton fields, but hand irrigation was labor-intensive, and using a coal-powered engine was not cost-effective. Shuman proposed that British capitalists invest in his solar energy venture to reduce coal costs.

Jeremy Shere, the author of the book “Renewable: The Power of Alternative Energy to Change the World” (2013), wrote about the events in Egypt at that time: “Heated to just over 93 degrees Celsius, the water turned into low-pressure steam to power a specially designed 75-horsepower engine. As if by magic, powered only by sunlight, the engine pumped thousands of gallons of water from the Nile River, transforming the arid landscape.”

However, Shuman’s invention soon faced a double setback from the outbreak of World War I and the discovery of cheap oil in the Middle East and elsewhere. Dougherty noted that Shuman’s design was “somewhat technically complex, which may have made it burdensome to implement.”

Nevertheless, Shuman believed that “solar-powered engines” could replace dirty fuels if implemented on a large scale. As early as 1911, when writing for Scientific American, he predicted the vast solar energy farms we see today: “To establish a solar power plant, high efficiency, low installation and maintenance costs, clear operating times, and no special training for operators should be required… It is entirely possible to produce a solar power plant in this way of up to 10,000 horsepower or more. An ideal plant should have minimal accidents, thus it should be close to the ground to avoid being affected by storms. Each unit can be repaired without stopping operations, construction must be simple and understandable for an ordinary steam engineer, and wear must be minimized.”

Shuman passed away in 1919, and it took another 50 years for his ideas to be revitalized, as the 1973 oil crisis ended the era of cheap oil. Less than a decade later, the first full-scale solar power plant was inaugurated in California’s Mojave Desert. At its peak, this plant could generate enough energy to supply 230,000 homes.

More than a century after Shuman’s experiments, Egypt inaugurated the fourth largest solar power plant in the world, located about 40 km northwest of the Aswan Dam. The Benban solar park covers over 37 square kilometers and is so large it can be seen from space. This stands as a testament to Shuman’s vision of harnessing energy in the region.