What is the name of this lake and where is it located in the world?

It is Lake Kivu in Africa.

Lake Kivu, situated between the borders of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Central Africa), offers an extraordinarily beautiful landscape, surrounded by towering volcanoes and lush green hills adorned with tea, coffee, and banana plantations.

However, deep beneath the lake’s surface lies a frightening threat: water saturated with methane (CH4), carbon dioxide (CO2), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S). If released, this toxic combination could claim the lives of over a million people living along the lakeshore, as reported by Time magazine.

Currently, the gas-saturated water is kept below a heavy layer of salt, preventing it from rising to the surface. But that barrier could easily be breached by an earthquake, a volcanic eruption, or even the increasing pressure of the gases themselves. Lake Kivu is often likened to a ‘ticking time bomb’.

Nevertheless, in the eyes of scientists and experts, Lake Kivu also holds the potential to provide valuable energy for the local population. What have they done to transform this deadly lake into a ‘power reservoir’ for humanity?

Let’s explore!

The Most Unusual Lake in the World

Lake Kivu is one of the most unusual bodies of water in Africa. A collection of abnormal characteristics makes it a fascinating subject for scientists, as well as a potential hazard and a source of prosperity for millions living nearby.

Kivu is unlike most deep lakes. Typically, when the surface water of a lake cools—say, from winter air temperatures or rivers carrying snow in the spring—the cold, dense water sinks while warmer, less dense water rises from deeper in the lake. This process, known as convection, usually keeps the surface of deep lakes warmer than their depths.

But at Lake Kivu, this convection does not occur, leading to some of the most surprising and astonishing phenomena in the eyes of scientists.

Lake Kivu seen in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, photo taken on November 25, 2016. (Source: REUTERS / Therese Di Campo / File Photo)

Spanning the border between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kivu is part of a chain of lakes along the East African Rift (EAR), where the African continent is gradually being pulled apart by tectonic forces.

This process thins the Earth’s crust and triggers volcanic activity, creating hot springs beneath Kivu, providing it with a source of hot, gas-rich water deep at the lake’s bottom.

Microorganisms that survive in Lake Kivu utilize some of the carbon dioxide, along with organic materials sinking from above, to generate energy, subsequently producing additional methane as a byproduct. The lake’s great depth—over 457 meters at its deepest point—creates such high pressure that these gases remain dissolved.

This mixture of water and dissolved gases is denser than water, which is why the convection phenomenon mentioned earlier does not occur. The deeper water is also saltier due to sediment from the upper layers of the lake and minerals from the hot springs, further increasing density. As a result, according to lake researcher Sergei Katsev from the University of Minnesota Duluth, Kivu is a layered lake with distinct water layers of varying densities, separated only by thin transitional layers.

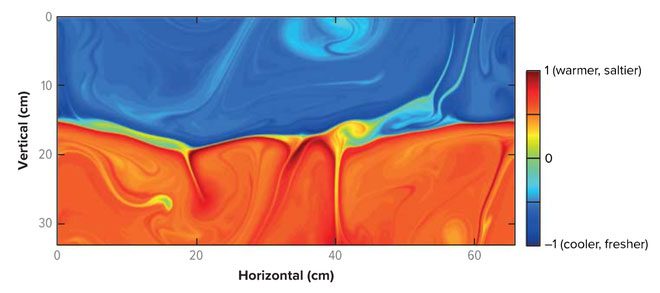

The unique composition of Lake Kivu in Africa prevents the mixing typically seen in other deep lakes, leading to unusual stratification of water. There is a clear density difference between each layer. The sharp transition between two of these layers is shown here, with the lower, warmer, saltier water below (in red) and the cooler, clearer water above (in blue). The boundary between the two layers is only a few centimeters thick. (Source: KM)

Alfred Wüest, a freshwater physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne, elaborates: “The water layers of Lake Kivu can be nearly divided into two regions: a less dense surface water zone at a depth of about 61 meters—and below that, a dense saline water zone that itself is further stratified. However, there is still mixing within each water layer, but they do not interact with each other. Just consider that the entire body of water in Lake Kivu has been sitting for thousands of years without doing anything; that alone highlights the difference of Kivu.”

Lake Kivu is not just a strange site attracting scientific interest. Its unusual stratification and the trapping of carbon dioxide, methane, and H2S in the deeper layers raise concerns among researchers that Kivu could be a disaster waiting to happen.

“A Giant Gas Bomb”

About 2,253 km to the northwest of Kivu, there is a volcanic crater lake in Cameroon called Lake Nyos, which also accumulates and retains a large amount of dissolved gas—in this case, carbon dioxide—from a volcanic vent at the lake’s bottom.

On August 21, 1986, the deadly potential of that gas reservoir was horrifically demonstrated. Possibly due to a landslide, a large volume of water was suddenly displaced, causing the dissolved CO2 to mix rapidly with the upper layers of the lake and release a ‘gas bomb’ into the atmosphere. As a result, a large lethal cloud suffocated around 1,800 people living in nearby villages.

The volcanic crater lake in Cameroon known as Lake Nyos. (Photo: United States Geological Survey)

Such events are referred to as limnic eruptions (or CO2 eruptions), and scientists worry that Lake Kivu may be ripe for a similar, perhaps even more dangerous event.

Lake Nyos is relatively small, measuring just over 1.6 km in length, under 1.6 km wide, and less than 213 meters deep. In contrast, Lake Kivu is 86 km long and 48 km wide.

Given its size, Lake Kivu could potentially experience a massive limnic eruption, in which several cubic kilometers of gas would be released into the atmosphere.

At the time of the CO2 eruption at Lake Nyos, around 14,000 people lived nearby; today, more than 2 million people reside in the vicinity of Lake Kivu, including approximately 1 million residents of the city of Bukavu in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. If Kivu were to undergo a CO2 eruption, researcher Sally MacIntyre from the University of California, Santa Barbara, states: “That event would be catastrophic!”

This is not merely a theoretical concern. Scientists have found what may be evidence of at least one past CO2 eruption at Lake Kivu, likely occurring 3,500 to 5,000 years ago, along with possibly some more recent eruptions. Sediment cores taken from the bottom of Lake Kivu have revealed features known as brown layers that differ from the surrounding sediment layers.

Lake researcher Sergei Katsev notes that these sediment bands are “very unusual, organic-rich layers”, which may result from previous CO2 eruptions of the lake.

Illustration of a gas explosion at Lake Kivu. (Source: Internet).

According to scientists, CO2 eruptions could occur for two reasons. If the water becomes fully saturated with dissolved gases, any additional carbon dioxide or methane pumped into the lake would rise and be released into the atmosphere.

The eruption could also be triggered when something forces the deep water layer along with its dissolved gases to mix with the upper layers, reducing pressure on the gases and allowing them to quickly escape from the solution and vent out, similar to shaking a can of soda and then opening it.

Moreover, Lake Kivu is situated in a seismically active area, so an earthquake could create waves in the lake that mix the water layers enough to release the trapped gases.

Climate change is also a potential culprit. At least one past eruption identified in the sediment record of Lake Kivu was caused by drought, which evaporated enough water from the lake surface to reduce pressure in the lower layers and release dissolved gases. Low water levels during drought periods could also make Kivu more susceptible to exceptionally heavy rains, which could wash enough accumulated sediment from numerous inflows into the lake to mix the layers together.

Sally MacIntyre remarks that the likelihood of a series of such events may increase as the planet warms. Climate change will bring more rainfall to East Africa, and “it will manifest as more extreme rainfall events with longer dry periods in between.”

Another possible cause could be volcanic activity beneath Lake Kivu or from surrounding volcanoes, but scientists believe the risk of this is low. An eruption in 2002 from the nearby Mount Nyiragongo did not provide enough material to disrupt the bottom layers of Kivu. Modeling studies have indicated that the volcano beneath the lake would also not cause a large enough disruption, said Sally MacIntyre.

Regardless of the culprit, the consequences would be the same: Accumulated gases would be released from their dissolved state, creating dense clouds of carbon dioxide and methane, which could displace oxygen and suffocate both people and animals living nearby. And if a sufficient amount of methane is released into the air at Kivu, there is an additional risk that it could ignite.

Sergei Katsev stated that Lake Kivu is regularly monitored for signs of increasing gas concentrations, so a sudden water surge “would not surprise us.” More than a dozen seismic stations also measure activity near the lake in real time.

In 2001, an effort began to mitigate the risk of another disaster at Lake Nyos by siphoning water from the bottom of the lake through a pipe to the surface, where carbon dioxide could be released into the air at a safe rate. Similar efforts are currently underway at Lake Kivu.

Transforming the “killer lake” into a vast energy source

As gas concentrations rise in the depths of Kivu, the risks also increase.

Alfred Wüest, an aquatic physicist at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, and his colleagues found that from 1974 to 2004, carbon dioxide levels increased by 10%, but the greater concern at Lake Kivu is methane concentration, which rose by 15 to 20% during the same period.

However, there may be a way to turn the danger at Lake Kivu into an “opportunity.” The same type of gas that could cause a deadly natural disaster also has potential as a renewable energy source for the region.

For the Rwandan government, the methane-rich waters are not just a threat to be mitigated but also an opportunity. The country, like much of Africa, lacks sufficient electricity to meet the growing demands of its population. Harvesting an estimated 60 billion cubic meters of methane from the depths of the lake could power the nation at its current rate for 400 years—a prospect that could change the landscape in a country with limited alternatives to expensive diesel fuel imports.

In 2008, Rwanda launched a pilot program to extract methane from Lake Kivu for use as natural gas. By 2019, Rwanda had signed contracts to export bottled methane.

Moreover, when the KivuWatt project “flipped the switch” on December 31, 2015, it exceeded expectations, generating over 25 megawatts of energy from day one.

The new KivuWatt power plant – harnessing trapped methane deep within Lake Kivu – is built by the American energy company ContourGlobal. (Source: Werner Krug / ContourGlobal)

Clare Akamanzi, CEO of the Rwanda Development Board, told Reuters in 2019 that bottled methane would help reduce local dependence on wood and charcoal, fuels that most households and tea processing factories rely on in this East African nation of tens of millions.

The methane is extracted for use as fuel, and CO2 is pumped back down to the bottom of the lake. Sergei Katsev stated: “They take this gas, transport it through pipes on land, and burn it like you would burn fossil fuels to generate electricity.”

This harvesting could help mitigate the risks posed by gas accumulation in the lake, although it will not eliminate it entirely. However, for a lake with multiple lurking dangers below, any effort is beneficial and commendable.

Once KivuWatt reaches its capacity of 100 megawatts, it is expected to make a significant difference for Rwanda, a developing nation striving for universal electricity access.