Software engineer Margaret Hamilton played a crucial role in helping Apollo 11 astronauts land on the Moon and return safely to Earth.

In 1969, just minutes before the Eagle module of Apollo 11 landed on the Moon’s surface, the computer screen suddenly displayed a warning, forcing NASA to consider whether to abort the historic mission. Fortunately, software engineer Margaret Hamilton had anticipated what could go wrong, assisting the control center in making the right decision. Moments later, Neil Armstrong successfully landed the Eagle module and made history as the first person to walk on the Moon.

Hamilton was only 32 years old when she led a team of programmers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to design the flight software for the Apollo 11 mission. Without her hard work and leadership, not only could the mission have failed, but the three Apollo astronauts might have lost their lives during the mission.

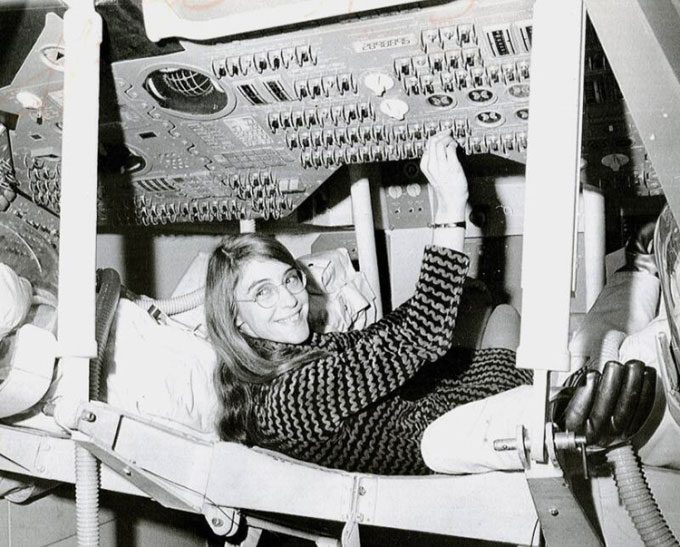

Margaret Hamilton. (Photo: WIRED)

Who is Margaret Hamilton?

Margaret Hamilton was born on August 17, 1936, in Paoli, Indiana, in the Midwest of the United States. Her family later moved to Michigan, where Hamilton attended the University of Michigan for a time. However, she quickly transferred to Earlham College in Indiana, where she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics.

In 1959, Margaret Hamilton took a job at MIT as a programmer working with Edward Norton Lorenz, the father of chaos theory. At that time, Hamilton was 24 years old, and her husband had just enrolled in Harvard Law School. For the next three years, Hamilton supported her family by writing software and programming weather systems.

A few years later, Hamilton applied to work on a major project: coding for human moon landings. She was accepted and became the first programmer to join the Apollo project. By 1965, Hamilton was leading a team of programmers at MIT’s Draper Laboratory.

Hamilton’s team was responsible for designing the flight software for the historic Apollo 11 mission. “I was drawn to both that great idea and the fact that it had never been done before,” Hamilton shared.

Margaret Hamilton stood out in the Apollo project. She was not only a woman—something quite unusual at that time—but also a “working mother.” When she went to the lab at night and on weekends, she often brought her young daughter, Lauren, along.

Margaret Hamilton examining the lunar module of the Apollo 11 mission. (Photo: NASA)

Coding for Human Moon Landings

Initially, NASA did not think the Apollo mission would require complex software. According to MIT professor David Mindell, software was even left off the schedule and budget.

It wasn’t long before NASA realized that the mission would fail without proper software, and by 1968, over 400 programmers were working on Margaret Hamilton’s software team. The team wrote and tested software for two Apollo computers: one on the command module and one for the lunar module.

If a disaster occurred and all eyes were on the Apollo mission, blame could have fallen on Hamilton. “I always imagined the headlines in the newspapers, and if they talked about a disaster, I would be named,” Hamilton recalled.

In the 1960s, creating software programs for a space mission was no easy task. Hamilton and her team wrote code by hand on sheets of paper, then used machines to punch holes in cards that were fed into computers as instructions.

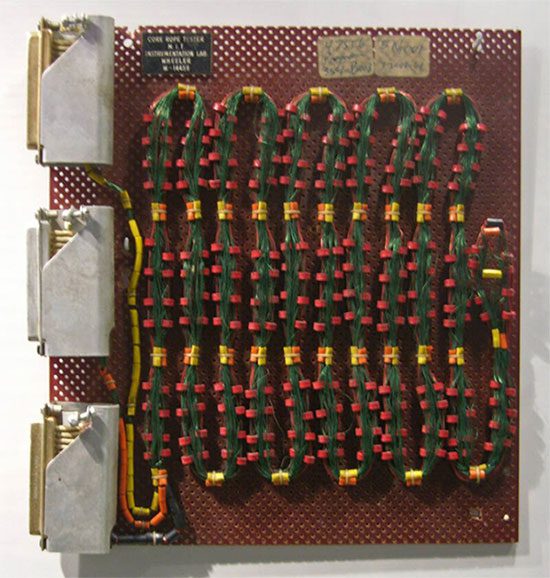

After testing their punched card code on a Honeywell mainframe to check for any errors during simulated landings, the codes were sent to a nearby Raytheon factory. There, skilled women threaded the 0s and 1s of the program through magnetic loops representing the program’s 1s and 0s: a copper wire going through a loop meant 1, while going around the loop meant 0.

These women were all skilled seamstresses. Their wiring created a hard-coded program for the modules that was virtually indestructible.

The two Apollo computers had to calculate navigational equations from space; otherwise, the mission would end in failure. The computers had about 72 kilobytes of memory—not even a millionth of the capacity of a modern mobile phone. They could store 12,000 bits—representing either 1 or 0—in core memory but only 1,000 bits in their temporary working memory.

The way copper wires threaded through the loops of memory, representing the actual guidance software code used for the moon flight. (Photo: Wikimedia)

How Margaret Hamilton’s Daughter Saved Apollo 11 Mission

One day, Lauren pressed a button on the simulator and disrupted the system Hamilton was testing. Just by pressing one button before launch, Lauren erased navigational data from the system’s memory. “I thought: Oh my God! This could accidentally happen during a real mission,” Hamilton recalled.

Hamilton reported the incident to her superiors and suggested changing the program, but NASA did not want her to write additional code to fix the issue, as adding code meant the risk of introducing more bugs. Instead, they decided to train astronauts to never make that mistake.

However, in the following mission (Apollo 8), astronaut Jim Lovell made the same mistake. This proved Hamilton correct, and additional code needed to be written to fix the error in case of an incident.

Hamilton referred to it as the Lauren error. “This error crippled the system and required the mission to be reconfigured. Eventually, NASA allowed me to implement the change in the program,” the software engineer shared.

The Change Program That Fixed the Issue

During the Apollo 11 mission, Margaret Hamilton focused on monitoring the software designed by her team that guided astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin toward the Moon’s surface.

Just three minutes before landing, a heart-stopping alert suddenly flashed on the screen, warning the astronauts of an emergency and prompting a decision on whether to land or abort. According to some reports, a radar switch was in the wrong position, causing the computer to overload.

Fortunately, Hamilton had prepared for this situation years in advance. Thanks to the error detection and recovery mechanisms Hamilton had written, the software restarted and focused on its highest priority task: landing the Eagle module on the Moon’s surface.

Jack Garman, a NASA computer engineer responsible for mission control, recognized the significance of the errors displayed on the screen and immediately informed the astronauts to continue guiding the lander, according to MIT.

“The software not only informed everyone that there was a hardware issue but also helped to resolve it. Fortunately, those at Mission Control trusted our software,” Hamilton added. “It was a relief when the module landed successfully. The astronauts were safe, and the software worked perfectly.”

Margaret Hamilton receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom. (Photo: Lawrence Jackson)

In 2016, then-President Barack Obama awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom—one of the two highest civilian honors in the United States—to Hamilton. “Our astronauts didn’t have much time, but fortunately, they had Margaret Hamilton,” Obama honored the significant contributions of the software engineer in humanity’s historic mission.