Marie Curie (1867 – 1934) is one of the pioneering scientists in the study of radioactivity. Her achievements are monumental, influencing later atomic physicists and earning her two prestigious Nobel Prizes. The discovery of the neutron by Sir James Chadwick and the artificial radioactivity by Irène and Frédéric Joliot-Curie both stem from Curie’s research.

1. Early Years.

|

|

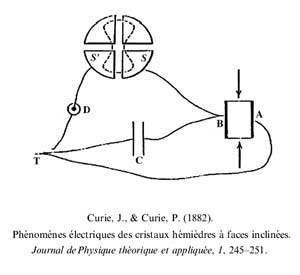

Quartz Crystals |

On November 7, 1867, in Kraków, a small town near the capital Warsaw in Poland, Professor Wladislaw Sklodowski and his wife welcomed their youngest daughter, Marya Sklodowski. From the moment she was born, the Sklodowski family encountered misfortune, as her mother suffered from a terminal illness: tuberculosis. Despite her love for her children, Mrs. Sklodowski never dared to hug them. Lacking maternal affection, little Marya often clung to her elder sister Zosia to hear fairy tales. Additionally, Marya loved gazing at her father’s scientific instrument cabinet, which contained numerous items: test tubes, barometers, scales, and geological specimens.

Marya’s family life was not joyful, and the national situation was equally bleak. Around 1872, when Marya was five years old, Poland was torn apart by three empires: Russia, Germany, and Austria. Her homeland fell under the influence of the Tsar. After the failed popular revolution of 1831, King Nicolas of Poland, under Russian manipulation, harshly suppressed patriotic revolutionary elements: imprisonments, exiles, and confiscation of property ensued. Furthermore, the government intentionally imposed an inhumane educational policy: a policy of ignorance. While science and philosophy began to flourish in Europe, the ideas of Auguste Comte, Darwin, and the discoveries of Pasteur and Faraday could not penetrate Poland.

In such circumstances, young Marya began her schooling. At first glance, she did not appear particularly intelligent; in fact, with her slightly elongated face and hazy brown eyes, she seemed somewhat dull. However, Marya was known for her academic excellence from a young age. Always two to three years behind her peers, she consistently ranked at the top of her class in all subjects: from core subjects like mathematics, history, and literature to electives like French, German, and even the Bible.

When Marya turned ten, her beloved sister and confidante Zosia tragically succumbed to an infectious disease brought from school: lice. Shortly after, their mother, after years of battling pulmonary tuberculosis, passed away, leaving her husband with the burden of raising four young children: one boy Joseph and three girls Hela, Bronia, and Marya, all of school age.

In 1883, at the age of 16, Marya graduated from secondary school with honors from the examination board. At that time, her brother Joseph was studying at the Medical University, and her sister Bronia had also completed secondary school and aspired to become a doctor. However, during that era, medical schools did not admit female students, so she had to seek a teaching position.

|

|

Piezoelectricity |

In 1884, Bronia moved to France to study at the University of Paris. She chose France partly because the Sorbonne University had many renowned professors, but mainly because France was a land of freedom, a desire shared by students worldwide at that time and in all eras. In France, diverse opinions were welcomed, a necessary condition for all progressive work in Science and Art. While Bronia studied to become a veterinary doctor in Paris, Marya sought a teaching position in a remote rural area.

2. Studying Abroad.

Teaching was not a profession that Marya enjoyed. After six long years of such a dry existence, in 1891, Marya decided to write to Bronia, asking her for help to study in France. On the day of her departure, Marya hesitantly told her father: “Father, I won’t be gone long; just two or three years of study, and I will come back to live with you forever.” However, Marya could not keep this sincere promise. A scientist, a husband, and a soul mate kept her in France, that person being Pierre Curie.

Upon arriving in France, Marya “translated” her name into French as Marie: Marie Sklodowski. Marie did not pursue medicine, dentistry, or pharmacy, which were popular fields among women at the time. For reasons unknown, she chose pure science. Initially struggling with the language, Marie received guidance from a talented young professor, Paul Appell. Additionally, she learned from Professors Gabriel Lippmann and Edmond Bouty. She also met prominent physicists of the time like Jean Perrin, Charles Maurain, and Aimé Cotton.

Life as a student abroad was challenging, compounded by financial difficulties: expenses for food, education, supplies, and daily bus fares to school. Winters in Paris were harsh, yet this brave Marya committed herself to her studies, and Heaven rewarded her perseverance: after three years of study, she graduated at the top of her class and received her Bachelor of Science degree in 1893. The following year, she placed second in the Mathematics Bachelor examination. After completing her studies, Marie intended to return home, but having gained theoretical knowledge, she wished to serve her country not merely as a professor, but through the practical skills of an engineer, aiming to assist her compatriots with tangible projects.

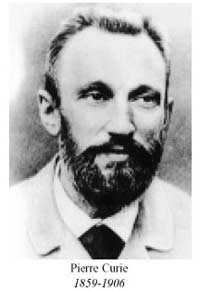

In 1893, through the introduction of Mrs. Dydynska, also Polish, Marie applied for the Alexandrowitch scholarship to study metallurgy. She was introduced to a young professor researching the magnetic phenomena of iron and steel: Professor Pierre Curie. Pierre Curie was born on April 19, 1859, in Paris, the second child of Dr. Eugène Curie. At the age of 16, Pierre graduated from high school, and at 18, he earned his Bachelor of Science degree, subsequently becoming an instructor at the University of Paris in 1878. After graduating, Pierre and his brother Jacques immersed themselves in experimental projects, studying the piezoelectricity of crystals, particularly quartz.

In 1893, through the introduction of Mrs. Dydynska, also Polish, Marie applied for the Alexandrowitch scholarship to study metallurgy. She was introduced to a young professor researching the magnetic phenomena of iron and steel: Professor Pierre Curie. Pierre Curie was born on April 19, 1859, in Paris, the second child of Dr. Eugène Curie. At the age of 16, Pierre graduated from high school, and at 18, he earned his Bachelor of Science degree, subsequently becoming an instructor at the University of Paris in 1878. After graduating, Pierre and his brother Jacques immersed themselves in experimental projects, studying the piezoelectricity of crystals, particularly quartz.

In 1883, Jacques was appointed a professor at the University of Montpellier, while Pierre became a senior lecturer at the School of Physics and Chemistry. In 1895, Pierre earned his Doctorate in Science, and in the spring of 1894, while conducting research on the electromagnetic phenomena of iron and steel, Pierre met Marie Sklodowska to gain more experience. Upon first meeting the Bachelor of Science and Mathematics from the Sorbonne, Pierre felt an affinity and respect for this talented woman. At that time, Pierre was 35 years old, still single due to his dedication to research. After several meetings and discussions with Marie about science, he quickly saw in her the image of an ideal wife. For Marie, after a failed first love in Poland, she wanted to erase matters of romance. She found Pierre very worthy, but remembering her elderly father and her vow to study quickly to return to him and serve her homeland, she left Paris. As she prepared to return home, Pierre pleaded, “You are a talented person. You should return to France to study Science. You cannot abandon Science.”

Marie Sklodowska was the first female engineer in Poland, but at that time, people did not have much faith in women’s abilities, so she was not given significant opportunities. Feeling disheartened, less than a year in her homeland, Marie decided to return to France, unable to abandon Science and be apart from Pierre. Ten months later, Marie accepted Pierre’s marriage proposal. Their wedding was held simply on July 25, 1895: apart from close family members, such as Dr. Eugène, Pierre’s father, Professor Sklodowski, Marie’s father, and Bronia and Jacques, they invited only a few close friends. In this new family, only Pierre earned money, and it was not substantial, while Marie had not yet secured employment; she was merely a brilliant student and a talented scientist. After two Bachelor degrees, Marie earned her Master’s degree in Science and continued her research on the magnetic properties of iron and steel. In July 1897, Marie gave birth to her first daughter, naming her Irène. From then on, the Curie family had new needs. Fortunately, Pierre arranged for Marie to work as an assistant in his Physics laboratory, marking the beginning of her career as one of the world’s leading female scientists.

3. Scientific Research.

Upon reading the research papers of physicist Henri Becquerel and after consulting her husband, Marie Curie was determined to explore the still obscure realm of physics, little known to many. At that time, scientists had only identified strange substances that emitted rays, but no one knew how many such substances existed or how they differed in their rays. These substances were collectively named “radioactive materials” by physicists. After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, Henri Becquerel theorized that radioactive rays had the same origin as X-rays. He conducted numerous experiments with the radioactive rays of uranium, similar to those with X-rays, and observed that the two rays shared similar properties. Becquerel wondered why radiation occurred and where radioactive substances sourced their energy from, even though the energy was minimal, to emit rays. His research was just the beginning; the understanding of radioactive laws awaited the genius of Pierre and Marie Curie to be fully uncovered.

Upon reading the research papers of physicist Henri Becquerel and after consulting her husband, Marie Curie was determined to explore the still obscure realm of physics, little known to many. At that time, scientists had only identified strange substances that emitted rays, but no one knew how many such substances existed or how they differed in their rays. These substances were collectively named “radioactive materials” by physicists. After Wilhelm Röntgen discovered X-rays, Henri Becquerel theorized that radioactive rays had the same origin as X-rays. He conducted numerous experiments with the radioactive rays of uranium, similar to those with X-rays, and observed that the two rays shared similar properties. Becquerel wondered why radiation occurred and where radioactive substances sourced their energy from, even though the energy was minimal, to emit rays. His research was just the beginning; the understanding of radioactive laws awaited the genius of Pierre and Marie Curie to be fully uncovered.

After a short period of research, Marie Curie discovered that not all of the uranium was radioactive; rather, it contained only a tiny portion of radioactive material. While she understood that the proportion of radioactive material in uranium was low, she was unsure of the exact amount. She estimated it to be about one part in a thousand. In reality, it was later determined to be much smaller: one part in a million. However, the Curies’ contribution was crucial in making the scientific community aware that there were many different radioactive materials, even though many were variants of one another, and that non-radioactive elements like lead and gold were also variants of radioactive substances. This insight was vital as it led to the discovery of nuclear fission and the eventual development of atomic bombs.

Initially, Curie identified two distinct radioactive substances: the first, discovered in the summer of 1891, was named “Polonium” in honor of her beloved Poland, and the second, discovered a few months later, was called “Radium.” However, their findings were not immediately accepted by the scientific community. Many skeptics refused to acknowledge the existence of Polonium and Radium, arguing that each substance must have its own physical and chemical properties. They questioned the atomic mass and molecular mass of Radium, its affinity for other substances, its salts, its color, and its solubility. These numerous questions baffled the young scientists. To answer the skeptical chemists, Pierre and Marie Curie needed to isolate pure Radium.

The raw material containing Radium is pitchblende.

Pitchblende is a substance used in the glass industry. It is quite expensive, and the amount of Radium it contains is limited. With their meager salaries, how could the two scientists continue their research? Fortunately, a Belgian glass manufacturer, having heard of the Curies’ reputation, agreed to transport large quantities of surplus pitchblende to France for the researchers. Another stroke of luck came when Pierre managed to secure an old house from the University of Science, where they could store pitchblende and set up a laboratory.

Over the four years from 1898 to 1902, after refining 8 tons of pitchblende, the Curies managed to isolate 1 gram of pure Radium. This was the first gram of Radium in the world, valued at 750,000 gold francs. Radium indeed became one of the most precious metals. From this point onward, Radium was officially “born” through the efforts of the Curies, with a molecular weight of 225.

Over the four years from 1898 to 1902, after refining 8 tons of pitchblende, the Curies managed to isolate 1 gram of pure Radium. This was the first gram of Radium in the world, valued at 750,000 gold francs. Radium indeed became one of the most precious metals. From this point onward, Radium was officially “born” through the efforts of the Curies, with a molecular weight of 225.

In 1898, the University of Sorbonne was looking for a Physics professor. Pierre applied for the position to earn a higher salary. However, since he had never attended a pedagogical college or engineering school, he was rejected. In 1900, Pierre Curie applied for a professorship at the Polytechnic School with an annual salary of 2,500 francs. This salary was still insufficient for the Curie family. Meanwhile, the University of Geneva in Switzerland sent him an invitation for a Physics professorship with an annual salary of 10,000 francs, along with two assistants and a fully-equipped research room. It was an unexpected stroke of good fortune. However, Geneva was too far away, and the Belgian glass company refused to transport pitchblende there. Between science and money, Pierre chose science and wrote a thank-you letter to the Dean of the University of Geneva.

Shortly after, Pierre Curie was invited by the Vice-Dean of the University of Sorbonne to teach Physics for the Special Certificate in Physics and Chemistry (S.P.C.N.), while Marie Curie was appointed as a professor at the Normal School for female students in Sèvres. The family finances improved, and the Curies could now focus on their scientific endeavors.

In 1902, the results of the discovery of Radium were published. Professor Mascart, impressed by Curie’s talent, encouraged him to apply for the Academy of Sciences. However, during the voting, the Academy selected the opposing candidate, Amagat. At this time, Professor Paul Appell was appointed as the Dean of the University of Science in Paris. To console Pierre, Appell requested the French Minister of Education to award a medal of honor to the scientist, and before presenting the medal, Appell urged Marie Curie to convince her husband to accept it. But Pierre declined, stating that he needed a laboratory, not a medal to wear. Throughout his life, Pierre Curie always hoped to establish a research facility where anyone interested in radioactive materials could freely use it.

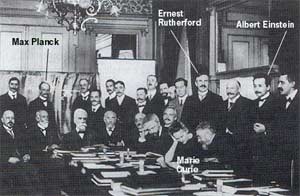

After the discovery of Radium, the fame of Pierre and Marie Curie spread beyond France. Since 1900, universities and research centers in England, Germany, Denmark, the United States, and others began contacting the Curies for information about Radium. Physicists raced to understand radioactivity, such as Boltzmann, Crookes, Paulsen, Ramsay, and many others, discovering new substances like Mesothorium, Ionium, Protactinium, radioactive lead, and radioactive helium.

|

|

Marie Curie with her two daughters |

In 1903, Marie Curie was awarded a Doctorate in Science with the highest honors by the University of Sorbonne for her dissertation “Research on Radioactive Materials.” That same year, the Royal Society of London invited the Curies to speak in England. Shortly thereafter, Sweden voted to award the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics, half to Henri Becquerel and half to Pierre and Marie Curie for their work in discovering radioactive materials. The Curies received 10,000 gold francs. However, upon receiving the joyous news of the Nobel Prize, the scientists were beset by disturbances: curious onlookers and reporters crowded around their home, creating noise and distractions for the Curies. They preferred a quiet working environment and were annoyed by the attention, as they did not want to be treated like movie stars. Marie Curie remarked, “In science, we should focus on the material and not the personalities.”

After the international recognition, Pierre Curie gained acknowledgment in France. In 1904, he was appointed as a full professor of Physics at the University of Sorbonne. Before accepting, he insisted on establishing a laboratory. This time, the French Ministry of Education no longer attempted to award useless medals but agreed to build a research center, allowing Marie Curie to lead the Physics department under her husband’s supervision, along with two assistants. In 1904, the Curies received another piece of good news: Marie gave birth to their second daughter, Eve Curie. In 1905, Pierre Curie was elected to the Academy of Sciences of France.

However, glory did not last long for the scientist. On April 19, 1904, after leaving the Gauthier-Villars publishing house to return home, Pierre Curie, lost in thought while crossing the street, was struck by a horse-drawn carriage and suffered fatal head injuries on Dauphine Street in Paris. Pierre Curie was an outstanding physicist and one of the founders of modern physics. In his memory, on May 13, 1906, the University of Sorbonne exceptionally invited Marie Curie to take over her husband’s position as a lecturer. Marie Curie became the first female professor at the University of Sorbonne, Paris.

Marie Curie became a full professor at the University of Sorbonne in 1908. That same year, she published a book titled The Works of Pierre Curie. In 1910, her work Treatise on Radioactivity (Traité de Radioactivité), spanning 960 pages, contained the most groundbreaking scientific knowledge of that time on the subject of radioactivity.

4. The Second Nobel Prize.

Marie Curie’s fame soared. Many foreign universities honored her with honorary doctorates.

In 1910, France intended to award Madame Curie the Knight’s Medal, but she declined the honor, recalling her late husband Curie’s feelings about such accolades. A few months later, many friends encouraged her to run for a position at the Academy of Sciences. Prominent figures supporting her included the great scientist Henri Poincaré, Dr. Roux, Professor Émile Picard, and Professors Lippmann, Bouty, and Darboux. However, during the elections, physicist Édouard Branly won the vote. Was it possible that the male members of the Academy still held biases against women, leading to Madame Curie’s rejection? Once again, Sweden corrected France’s mistakes: In December 1911, Marie Curie received another Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work in discovering radium. She remains the only person to have won two Nobel Prizes, surpassing both her male and female peers of past and present.

In 1911, Polish intellectuals planned to establish a research facility for radioactivity in Warsaw, intending to invite Marie Curie to lead this center. In May 1912, a delegation of Polish professors traveled to France to meet her. At this time, Marie Curie was torn between her longing for her homeland and memories of Pierre, along with her aspiration for a Radium Institute then under construction in Paris. Ultimately, she sent a letter declining the offer, placing her trust in the research capabilities of two Polish assistants who had worked with her.

In 1911, Polish intellectuals planned to establish a research facility for radioactivity in Warsaw, intending to invite Marie Curie to lead this center. In May 1912, a delegation of Polish professors traveled to France to meet her. At this time, Marie Curie was torn between her longing for her homeland and memories of Pierre, along with her aspiration for a Radium Institute then under construction in Paris. Ultimately, she sent a letter declining the offer, placing her trust in the research capabilities of two Polish assistants who had worked with her.

In 1913, Marie Curie traveled to Poland for the inauguration of the radioactivity research facility. She delivered a speech on science in her native language to a large audience. By July 1914, the Radium Institute in Paris was completed on Pierre Curie Street. This was the “Castle of the Future,” a place Pierre had long dreamed of living in to conduct research, and now Marie continued his legacy.

World War I broke out. Unlike many women, Curie did not join nursing units; instead, she focused on the lack of X-ray facilities in hospitals. She equipped a car with X-ray machines and, along with her daughter Irène, traveled to care for wounded soldiers at various frontlines. As the number of injured increased, Marie Curie installed an additional 220 X-ray rooms in vehicles and on the ground. She even utilized a rare and invaluable amount of radium for treating war victims. Moreover, the demand for X-ray specialists prompted Curie to suggest that the French government urgently establish a training program. This initiative was implemented at the Radium Institute, with lectures given by Curie, her daughter Irène, and Marthe Klein.

In 1918, the war ended, bringing peace to France and independence to Poland after a century and a half of foreign domination. For many years, Curie had devoted her energy and financial resources to the war effort, donating her Nobel Prize money to the French government. The war disrupted her research activities and took a toll on her health.

In May 1920, Marie Curie received journalist William Brown Meloney. During their conversation, she expressed the need for radium to continue her research, although it was exceedingly expensive. Moved and inspired, Meloney returned to the United States and organized a fundraiser among American women to purchase radium for the esteemed scientist. She also urgently invited Curie to visit the United States, but Curie was apprehensive about the crowds and publicity. Eventually, she agreed. In early May 1921, Marie Curie and her two daughters boarded the Olympic to travel to America.

In May 1920, Marie Curie received journalist William Brown Meloney. During their conversation, she expressed the need for radium to continue her research, although it was exceedingly expensive. Moved and inspired, Meloney returned to the United States and organized a fundraiser among American women to purchase radium for the esteemed scientist. She also urgently invited Curie to visit the United States, but Curie was apprehensive about the crowds and publicity. Eventually, she agreed. In early May 1921, Marie Curie and her two daughters boarded the Olympic to travel to America.

On May 20, U.S. President Warren G. Harding presented Marie Curie with a gram of radium. In Philadelphia, she received honorary degrees, gifts, 50 grams of mesothorium, and the John Scott Medal from the American Philosophical Society. Additionally, she was made an honorary doctorate at the University of Pittsburgh and Columbia University. Curie returned to France on June 28 of that year.

Due to her discoveries in radiation therapy, in early 1922, the Academy of Medicine in Paris elected Curie as a member. That February, she also became the first female scientist elected to the French Academy of Sciences. Marie Curie’s fame spread far and wide, earning her warm receptions in Argentina, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Czechoslovakia. On May 15, 1922, the League of Nations appointed her as a member of the International Education Organization.

Marie Curie’s dream was to see a Radium Institute established in Warsaw. The project took shape in 1925, and Curie traveled to Poland to lay the cornerstone for the Institute. However, upon its completion, the Warsaw Radium Institute lacked radium for research. In October 1929, Marie Curie traveled to the United States once again. She received a grand welcome, just as on her previous visit, and the U.S. once more supported the renowned scientist. On May 29, 1932, the Polish Radium Institute was inaugurated, fulfilling the wishes of the esteemed scientist.

Even at over 60 years old, Marie Curie continued to work tirelessly, often for 12 hours a day. Under her guidance, from 1919 to 1934, 483 scientific works were published by physicists and chemists at the Radium Institute, with Curie herself contributing 31 of these research papers.

Starting in December 1933, Curie’s health began to deteriorate. She had to adhere to a doctor’s dietary recommendations and occasionally returned to the countryside for a healthier atmosphere. During a trip in May 1934, Curie caught a cold. Despite her doctor’s advice to rest, she continued to work, reluctant to waste time in the laboratory. She suffered a relapse, with her illness lingering for months. She was seen bedridden in a white dress, her hair as white as snow, her high forehead adorned with closed eyes, and her arms limp, revealing bony hands marred by radiation exposure. Marie Curie passed away on July 4, 1934, at Sancellemoz Hospital, despite the dedicated care of distinguished doctors. She died of aplastic anemia (leukemia) caused by radiation from radium.

Starting in December 1933, Curie’s health began to deteriorate. She had to adhere to a doctor’s dietary recommendations and occasionally returned to the countryside for a healthier atmosphere. During a trip in May 1934, Curie caught a cold. Despite her doctor’s advice to rest, she continued to work, reluctant to waste time in the laboratory. She suffered a relapse, with her illness lingering for months. She was seen bedridden in a white dress, her hair as white as snow, her high forehead adorned with closed eyes, and her arms limp, revealing bony hands marred by radiation exposure. Marie Curie passed away on July 4, 1934, at Sancellemoz Hospital, despite the dedicated care of distinguished doctors. She died of aplastic anemia (leukemia) caused by radiation from radium.

On the afternoon of Friday, July 6, 1934, the funeral of the renowned scientist was held at Sceaux Cemetery. Her coffin was placed atop Pierre Curie’s grave, in accordance with her wish to be close to her husband in life and in death.

Marie Curie was the first renowned female scientist in the world. She pioneered research in radioactivity. In addition to her service to science, Marie Curie was a passionate patriotic citizen, not only for her homeland but for all nations she recognized. Marie Curie truly embodied the words of French writer Victor Hugo: “Serving one’s country is just half of the duty. The other half is serving humanity.”