Some Indigenous peoples in Guatemala, southern Mexico, and Belize today still use the Mam, Quiche, Cakchiquel, Kekchi, and Myathan languages, which are among the over thirty languages spoken by the Maya. A common feature of these different languages is their systematic way of naming a complete set of numbers, which is quite similar across the board.

Centuries of colonial rule, along with the advent of a market economy, have gradually replaced indigenous terms for numbers with borrowed Spanish words. For decades, people have stopped using indigenous languages to refer to large numbers, and even the names for single-digit numbers in indigenous languages are gradually fading away.

Everyday Numbers

Archaeological evidence provides very little information about the use of numbers in the economy of pre-Columbian America. However, it is well established that the Maya system was developed by counting on fingers and toes. For instance, in the Quiche language, the word for the number 20 is huvinak, meaning “whole body.” This counting method operates on a base-10 system: 11 is hulahuh, meaning one (1) plus lahuh (10). The way numbers are used is very much akin to how we count today, with the notable difference that the Maya needed to use classifiers to describe the items being counted, specifying whether they were round, long, or in a solid or liquid state. For example, when referring to cigarettes, the Yucatec say: “This is hun (one) dzit” (a long, cylindrical object) called chamal (a cigarette), rather than saying “this is a cigarette.”

The Official Solar Calendar

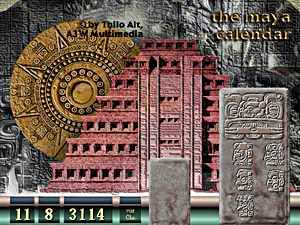

The Maya calendar is based on a solar year of 365 days, inherited from the ancient Zapotecs (in Monte Alban) and Olmecs (in La Venta and Tres Zapotes).

Maya Calendar Map (Photo: posteruniversum)

With a fixed length, the solar year is divided into 18 months, each consisting of 20 days (using a base-20 counting system), with 5 additional days added at the end of the year. Each month has a name that seems to bear no relation to agricultural cycles or festivals. The names of the months are passed down through tradition or may even have been borrowed from other languages or cultures. They only hold historical significance, unlike the month names in modern European languages, which derive from Latin and whose original meanings are still understood by some.

Days in the month are numbered sequentially from 0 to 19 placed before the month name (from 0 to 4 for the short month, which only has 5 days at the year’s end). Thus, each day is precisely named on the timeline. Years follow one another continuously with no leap years.

The Calendar of the Diviners

|

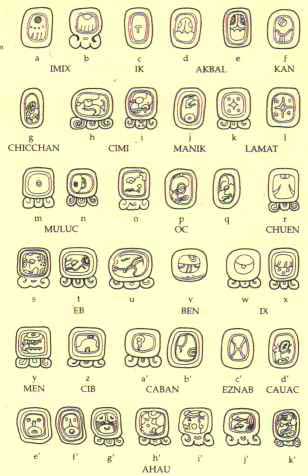

Maya Hieroglyphs (Photo: mayasite) |

In ancient times, the Quiche, Ixil, and Mam peoples still used the traditional 260-day Maya calendar for divination. Why 260 days? After interviewing numerous diviners in Chichicastenango and Momostenango, German anthropologist Leohard Schultze Jena discovered that this length was not random, but aligned with the human gestation period. Regardless of its origins, the base-20 system allows for dividing the 260-day year into 13 months, each with 20 days. Each day is named with a number from 1 to 13, combined with one of 20 names representing animals, natural forces, concepts, or abstract ideas whose meanings have been lost over time.

Similar to the solar calendar, the divination calendar is cyclical, with the last day of one cycle followed by the first day of the next.

Calendar Cycles

The interleaving of the 260-day calendar with the 365-day calendar creates a 52-year cycle, where each day is named differently. This cycle of 18,980 days (52 years of the solar calendar with 365 days per year, or 73 years of the divination calendar with 260 days per year) is known as the largest unit of time measurement for most pre-Columbian Central American cultures. Unlike the Mexicas and Aztecs, the Maya were familiar with multiple counting systems and used different units to measure longer time periods, but the Maya stand out as an exception among the major pre-Columbian cultures.

Hieroglyphs

We know that days and months were named, and largely pluralized. Today, many Indigenous diviners still use their own languages to name these days. Pre-Columbian Maya could write the names of all days in a calendar cycle using hieroglyphs. Four surviving codices with hieroglyphs are currently preserved in Paris, Dresden, Madrid, and Mexico City.

Countless inscriptions on stone, some wall carvings, and an abundance of decorative pottery serve as remarkable evidence of this unique writing system.

|

Maya Numerals from 1 to 13 using dots and bars |

The simplest way to record numbers from 0 to 19 is with dots (for units). For larger numbers, a symbol is used for 20. To record numbers larger than 40, a positional notation system is employed with a special symbol equivalent to our zero at the empty position. Each position represents a power of 20, with the third position multiplied by 18, specifically: the first position 20^0 = 1; the second position 20^1 = 20; the third position 18 x 20^1 = 360; the fourth position 18 x 20^2 = 7200; the fifth position 28 x 20^3 = 144,000, etc.

Counting Days

Very early on, and by no later than the Christian era, Central American Indigenous peoples invented a method to track time: counting days (cuenta larga, meaning “long count.”) This system operates independently of the aforementioned calendar cycles, counting days sequentially starting from a distant day that is somewhat mystical. This highly accurate day-counting system greatly assisted modern researchers in the early 20th century in establishing correlations between it and our calendar. The original purpose of this date-keeping system was to help the Maya systematize important historical days related to their deities or leaders.

Other Calendar Cycles

Ancient Maya also used other calendar cycles for historical, divinatory, or speculative purposes. For instance, from hieroglyphs G1-G9, the existence of a 9-day (or night) calendar cycle dedicated to 9 deities is known. Furthermore, a combination of shorter cycles of 7, 9, and 13 days, each cycle dedicated to a different type of deity, forms a 819-day cycle for divination purposes.

Astronomy

Not limited to observing stars and predicting celestial movements, Maya astronomers employed a sophisticated numbering and tabulation system, combined with hieroglyphs, to perform complex calculations involving millions.

Initially, their efforts focused on the Sun and Moon. They utilized years of varying lengths in nature. Typically, the standard year of 365 days was regarded as the baseline, but there could also be years of 364 days or 365 1/7 days, similar to the Julian calendar (the calendar of Julius Caesar).

|

Astronomy (Photo: art3w) |

The Moon consistently features in stone carvings of the calendars. This calendar often begins on a day based on the Moon’s phase and the position of that day within a lunar calendar of 6 months.

Maya astronomers also calculated the orbit of Venus, achieving an astonishingly close approximation of 584 days compared to calculations made by modern astronomers. But they did not stop there; the Maya manuscripts in Dresden also feature correction tables that allow for very slight adjustments compared to those values, and discovering these discrepancies required observation periods lasting decades, even centuries. Researchers also believe that the Maya succeeded in calculating the movements of several other planets, such as Mars and Jupiter, though this remains unproven.

Entering Pure Mathematics

For the Maya, the fundamental reason for constructing various calendars and astronomical calculations was rooted in religion, divination, and predicting the future. Their calendar specialists dedicated time to establishing correlations between different calendar cycles, using the least common multiple and other methods to forecast the future or connect the present with significant past events. In this way, they could also explore a bit about the destinies of their patrons—whether they were leaders or other individuals.

Practical calculations unraveled coordinated algorithms and theories characterized by probability. Many calculations were pushed far back into the past and forward into the future, impressively suggesting that the priests responsible for the calendars primarily sought to satisfy their own thirst for knowledge and to probe the limits of their mathematical capabilities. This allows us to assert that the Maya, like those before and after them—including the Babylonians, Greeks, Arabs, and Indians—possessed a remarkable pure mathematical intuition.

Berthold Riese, a German expert on Native American cultures, published Maya Kalender und Astronomic, a collective work edited by Ulrich Kohler (1988).