A new study reveals that hormone fluctuations throughout the menstrual cycle can change brain structure.

Scientists at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) have found subtle changes in brain structure in 30 women throughout their menstrual cycles. These changes correlate with the fluctuations of four types of hormones.

The researchers collected data from 30 women who do not use hormonal contraceptives and have regular monthly menstrual cycles.

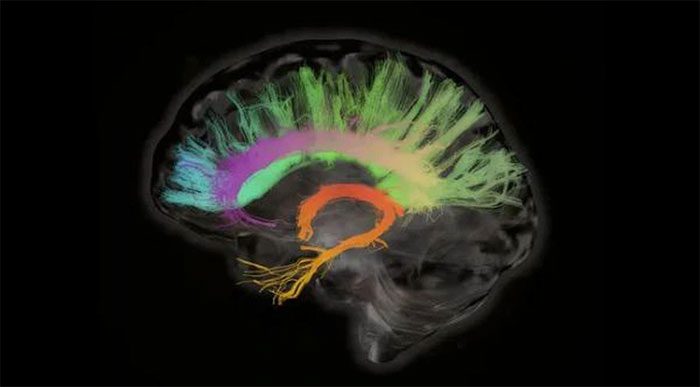

Colorful X-ray image of the human brain – (Photo: SHERBROOKE CONNECTIVITY IMAGING LAB).

They imaged the brains of women at three different points in the menstrual cycle: during menstruation, ovulation, and the luteal phase leading up to menstruation, which is often associated with premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

Through this process, the researchers gathered data on brain volume and two types of brain tissue: gray matter, which contains the main parts of brain cells, and white matter, which connects and facilitates communication between cells. They also measured cortical thickness – the thickness of the outer wrinkled layer of the brain made up of gray matter. Finally, they collected data related to how water diffuses through the brain’s white matter.

Dr. Erika Comasco, an associate professor of molecular psychiatry at Uppsala University in Sweden, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science that examining this water diffusion “allows us to better understand the structure of white matter fibers.”

While exploring the brain’s structure, the study also examined the fluctuations of four types of hormones throughout the menstrual cycle: estradiol (a type of estrogen), progesterone, luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

The results showed that estrogen and LH levels peak during ovulation, while progesterone peaks in the luteal phase. In contrast, FSH is more stable but also peaks during ovulation, as well as reaching relatively high levels at the end of the luteal phase and during menstruation.

Although the overall brain volume remained unchanged, increased progesterone was associated with an increase in brain tissue volume but a decrease in cerebrospinal fluid, the fluid that surrounds and protects the brain and helps it eliminate waste.

Importantly, the researchers still do not know whether these changes in the brain affect cognition or the risk of developing brain diseases and how they might influence this.