A jellyfish is currently agitated in a fish tank in California. Inside its seemingly simple body lies a remarkably complex set of genes.

|

|

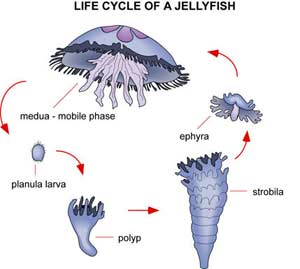

Life Cycle of Jellyfish |

For a long time, jellyfish have been regarded as simple and primitive animals. Observing them in a fish tank, one might easily believe this notion. Similar to their relatives such as goosefoot and corals, jellyfish appear to be completely simple creatures at first glance. They lack a head or tail, a back or belly, and even fins or legs. They do not have a heart either. Their gut resembles more of a bag than a tube, thus their mouth also serves as an anus. Instead of a brain, they possess a diffuse nerve net.

While a fish or a shrimp can swim quickly in a specific direction, jellyfish can only move sluggishly.

However, recent research findings have forced scientists to acknowledge that they have underestimated jellyfish and their relatives, known as the group of cnidarians (pronounced as nih-DEHR-ee-uns). Within their seemingly simple bodies lies a complex and remarkable set of genes, including many features beneficial for the development of human anatomy.

These discoveries have led to a completely new theory about the evolutionary process of animals dating back 600 million years. The search results have also attracted the attention of many scientists towards cnidarians as a model for studying the human body.

Dr. Kevin J. Peterson, a biologist at Dartmouth, remarked: “The biggest surprise is that cnidarians possess more complex genes than we thought. This has caused many to go back and realize that much of what they believed about cnidarians was completely wrong.”

Scientists have re-examined their developmental processes. Naturalists from the 18th century reluctantly categorized them within the animal kingdom, and that was it. They classified cnidarians as “tree-like animals,” somewhere between animals and plants.

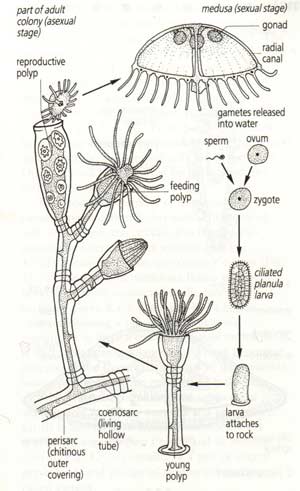

It wasn’t until the 19th century that naturalists began to understand their growth mechanisms from eggs, with their bodies developing from two layers of cells: the endoderm and the ectoderm.

|

|

Jellyfish |

Other animals, including humans and insects, develop their bodies from three layers of cells: mesoderm, endoderm, and ectoderm. This mechanism forms muscles, hearts, and other organs not present in cnidarians.

Cnidarians also have a different and simpler operational mechanism. Fish, fruit flies, and earthworms all have a head and tail, a back and belly, and left and right sides. Scientists reference the bodies of animals, including humans, by this symmetry mechanism. In contrast, cnidarians do not exhibit this symmetry. For instance, a jellyfish has a radial symmetry, extending from the center outward.

Biologists studying evolutionary processes view cnidarians as remnants of evolutionary stages. The first animals resembled sponges, essentially just cellular grids. Cnidarians may represent the next evolutionary stage, acquiring traits of cellular organization and simple nervous systems.

Fossil specimens seem to confirm this hypothesis. Many early animal fossils share similarities with jellyfish or other cnidarian species. The oldest fossils known to date date back to the Cambrian explosion, approximately 540 million years ago.

Some researchers believe that the evolution of the two-layer body plan marked the Cambrian period. Unlike their ancestors, two-layered animals have heads, allowing them to perceive their surroundings and direct their movement.

Recent research has altered this theory. The oldest fossils classified as cnidarians are only around 540 million years old. Dr. Peterson and his colleagues have proposed a method to assess the age of cnidarians by studying their DNA.

|

|

Structure and Life Cycle of Obelia – Cnidarians |

DNA has been changing at a normal rate for millions of years, following a molecular clock mechanism. Dr. Peterson estimates that the ancestors of the cnidarian group lived around 543 million years ago. In other words, cnidarians could not have appeared before two-layered animals by ten million years.

Genetic studies have also challenged all traditional theories about cnidarians. Starting in the 1980s, scientists researching two-layered animals discovered a gene system that formed their bodies. Some genes formed the head-to-tail axis, while others formed the back-to-belly axis.

Humans and insects may be dramatically different, but they both adhere to the fundamental developmental points of this genetic law. The findings suggest that this genetic law evolved from the ancestors of two-layered animals.

Dr. Mark E. Martindale from the University of Hawaii and his colleagues decided to search for the gene system that forms jellyfish and other cnidarians. They spent a significant amount of time reaching their results. They had to find species that could not only survive in the laboratory but also reproduce for research purposes.

Dr. Martindale’s team chose the starry goosefoot, a species abundant along the New England coast. Studying its life cycle and gene mechanisms required immense patience. Dr. Martindale stated, “We spent 9 to 10 years, but the results are like a gold mine.”

Researchers were astonished to find that some genes in their embryos resemble those that dictate the head-to-tail axis of two-layered animals, including humans. Even more surprising was the realization that these genes operate in exactly the same mechanism as the head-to-tail axis of two-layered species.

Subsequent research results show that cnidarians also possess other genes that follow the rules of symmetrical genetics. Genes that assist in forming the back-to-belly axis are also found on the opposite side of the starry goosefoot embryo.

The research findings prompt scientists to question why cnidarians utilize such a complex set of body-forming genes while their bodies appear quite simple. They conclude that cnidarians might be more complex than they seem, especially regarding their nervous systems.

John R. Finnerty, a biologist at Boston University collaborating with Dr. Martindale, said: “At the molecular level, their bodies have many regions that are unrecognizable.”

Dr. Finnerty believes that the nervous system of cnidarians will be entirely complex. He remarked: “The nervous system of cnidarians is structured like a nerve net, but that is just a simplified textbook description.”

|

|

Anemone – Cnidarians |

He also predicts that the research results will show that this nerve net is divided into distinct specialized regions similar to the human brain.

These discoveries have caused Dr. Peterson to reassess the evolutionary process of cnidarians. He stated: “It has completely changed my thinking about the evolution of animals in the early stages.”

He now believes that cnidarians are not simply among the earliest animals formed during the Cambrian explosion, but are one of the species within this phase, their evolution governed by the rules of predatory animals.

In a paper published in the journal Paleobiology, Dr. Peterson and his colleagues propose that the common ancestor of both two-layered animals and cnidarians was an ancient insect. This ancient insect, according to Dr. Peterson, lived around 600 million years ago, representing an important evolutionary model in animal evolution. Rather than filtering small prey simply, it had the capability to capture larger prey.

Dr. Peterson stated: “Once they could hunt for themselves, nothing could stop them.”

Some species have begun to cannibalize each other. The species with higher self-defense capabilities will have a better chance of survival. One way to avoid being preyed upon is to develop a larger body. Another strategy is to lay eggs in the water column rather than leaving them exposed on the ocean floor. Some animals also develop the ability to swim as they mature.

As the aquatic environment began to host a greater number of animals, cnidarians evolved into their current form. Early cnidarians anchored themselves to the ocean floor and grew upward, similar to modern-day seagrass and corals. During their development, they discarded the bilateral symmetry of their ancestors.

During this same period, cnidarians developed their unique weapon: specialized cells that form tiny stinging structures called nematocysts, which contain toxins that can paralyze their prey.

|

|

Sea Jelly |

Dr. Peterson suggests that as modern animals moved higher in the water column, some cnidarian species evolved to become more adept at hunting prey. Sea jellies are the ultimate product of this evolutionary process.

New discoveries about cnidarians have sparked a human interest in studying them more thoroughly. Star-shaped seagrass is currently being researched at the Genome Energy Department’s Joint Genome Institute, with plans to complete the study this year.

Scientists are anticipating many surprises from this genetic research. They have found numerous genes similar to those in vertebrates within the genetic framework of cnidarians. Clearly, these genes could not have developed in early vertebrate species.

These genes are much older and are related to the ancestors of cnidarians and bilaterians from 600 million years ago. Later on, they disappeared in the evolutionary branches of bilaterians such as insects and roundworms, which are currently the focus of significant research efforts.

In some respects, cnidarians serve as a more valuable model for human biology studies than fruit flies. It may be quite astonishing, but when observing a sea jelly in an aquarium, it feels as though we are looking into a mirror.