In North Dakota, paleontologists have discovered a rare and valuable specimen: a perfectly preserved part of a dinosaur’s body, akin to a mummy, thanks to… a crocodile.

According to Live Science, the specimen features skin that still appears “sparkling” and other soft tissues that are exceptionally well-preserved. This is invaluable to paleontologists as it significantly contributes to reconstructing the appearance of dinosaurs.

Most previously excavated dinosaur fossil specimens only consist of bones, as preserving soft tissues like skin and muscle over tens of millions of years is considered impossible.

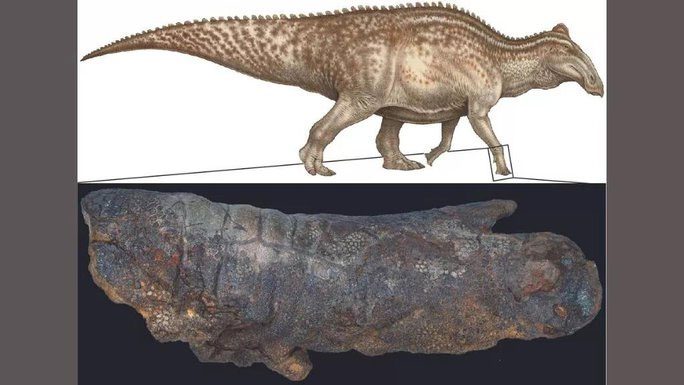

The famous dinosaur mummy (below) and a reconstruction of the whole animal, with the mummy marked belonging to the forelimb – (Photo: Natee Puttapipat)

One of the lead co-authors of the study, Dr. Stephanie Drumheller from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, stated that there was once a hypothesis suggesting that for an animal from the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods to become a mummy, it needed to be buried quickly, for instance, by something suddenly collapsing and sealing the animal inside.

However, this specimen was preserved in a completely different manner.

According to SciTech Daily, this dinosaur, which is an Edmontosaurus belonging to the gentle duck-billed dinosaur group, was attacked by a giant ancient crocodile. The remaining body part – according to thorough examinations – is riddled with wounds from the encounter.

It is these wounds, combined with the favorable surrounding environment, that helped absorb moisture and dry out the body perfectly, as they created openings for fluids to penetrate the dinosaur’s thick skin.

The way this mummy was dehydrated and dried could be due to materials in the environment that buried it; or it may have inadvertently lain on a dry, hot sandy area under the harsh sunlight, thus becoming a perfect piece of “dinosaur jerky.”

This dinosaur mummy was not newly discovered; it was excavated in 1999 at a farm in southwestern North Dakota, shrouded in many hypotheses.

Dr. Drumheller and her colleagues found it at a museum and decided to unravel the long-standing mystery.

Even after many years, specimens like this remain scientifically invaluable, especially as modern tools can help study it in greater detail without any invasive techniques.

The research has just been published in the scientific journal PLOS One.