Researchers at the University of Helsinki have developed a new nasal spray that could effectively protect users against the novel coronavirus (nCoV) and various variants, including Omicron.

In recent preliminary studies conducted on cells in petri dishes as well as in mice, the nasal spray was able to prevent the virus from infecting cells for up to 8 hours after a single dose. However, scientists will need to conduct further research before applying this therapy to humans. The experimental nasal spray was developed by a research team at the University of Helsinki, utilizing a method to combat nCoV that differs slightly from other approaches.

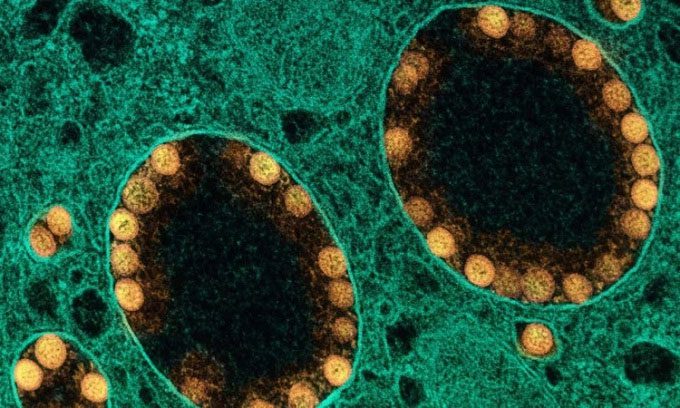

Yellow nCoV virus particles inside the membrane-binding vesicles of epithelial cells. (Photo: NIH)

“The preventive effect of the drug is to stop the transmission of nCoV,” said study author Kalle Saksela. “However, this is not a vaccine, nor is it a substitute for a vaccine; it acts more like an adjunct vaccine to enhance protection for those who have been vaccinated in high-risk contexts, particularly for individuals with weakened immune systems.”

Vaccines work by training the immune system to recognize pathogens, helping the body produce a supply of natural antibodies and immune cells that are appropriate for the pathogen should it appear in the future. We can produce monoclonal antibodies to combat nCoV in the laboratory. However, the treatment developed by the Helsinki research team uses a synthetic protein that is much smaller than antibodies. Yet, it can still recognize and bind to the virus’s spike protein. To enhance the potential of the protein, researchers clustered them into groups of three proteins.

Theoretically, these antibody-like molecules could actively inhibit any coronavirus they come into contact with, at least for a short period. In spray form, the protective molecules can be delivered directly to the upper respiratory tract, where nCoV infections typically initiate in most cases.

Saksela, a virologist at the University of Helsinki, emphasized that this treatment is not intended to replace vaccines or other medications. In a study published last December, Saksela and colleagues described the process of testing the nasal spray with pseudoviruses resembling nCoV variants as they infected cells in petri dishes and in living mice.

Omicron has become a variant of concern primarily due to numerous mutations that allow it to evade natural and artificial antibodies created to combat the original nCoV strain. However, the molecules developed by the research team target a very minimally mutated area on the spike protein of nCoV. Therefore, even Omicron can be easily inhibited.

At least that is what Saksela and his team observed in the laboratory. Regardless of whether it is Omicron, Delta, or the original nCoV strain, the virus was blocked after administering a dose of the nasal spray. In mice exposed to the Beta variant of nCoV, those treated with the spray had almost no virus in their upper respiratory tracts and lungs compared to the control group. The treatment also appeared to be safe and did not cause any serious harm.

Of course, the preliminary research has not yet been peer-reviewed. If further studies yield promising results, Saksela predicts that the nasal spray will still be useful even after the pandemic ends. “This technology is very cheap and easy to produce. The inhibitors work equally well against all variants. It also works with the SARS virus, so it could be used as an emergency therapy for future coronaviruses.”

Saksela is unsure how long it will take for the nasal spray to receive clinical trial approval and become available on the market. In addition to continuing research on COVID-19 treatments, the research team may also try to develop a similar nasal spray for other infectious respiratory diseases.