American scientists have discovered an easier method than sending robots to burrow through the icy crust of Saturn’s moon Enceladus in search of extraterrestrial life.

A recent study published in the Planetary Science Journal indicates that an orbital spacecraft equipped with additional instruments is sufficient for NASA to gather solid evidence of the presence of extraterrestrial life on the “ocean moon” Enceladus.

Enceladus, the massive icy moon of Saturn, is one of the locations where NASA is almost certain it could be a promising ground for extraterrestrial life, following the groundbreaking discoveries made by the Cassini spacecraft in 2014.

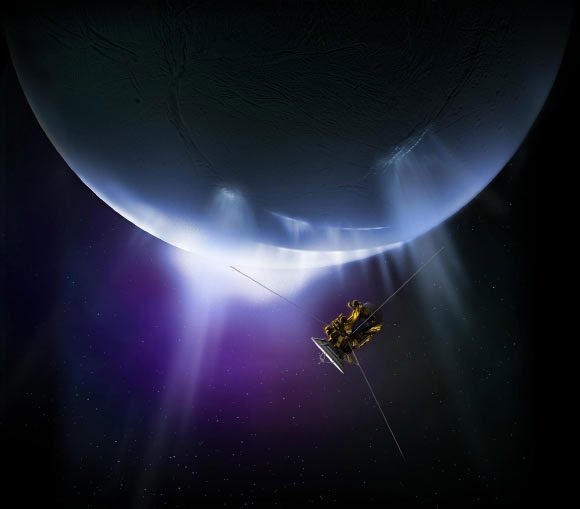

Cassini spacecraft and Enceladus – (Image: NASA)

Cassini not only identified a large ocean beneath the icy surface of Enceladus and collected water samples from its geysers, but it also analyzed and discovered organic molecules that form the basis of life. These geysers also released significant amounts of methane, which is one of the most reliable signs of life.

According to Sci-News, NASA has laid out a major plan for the upcoming decade to send a lander with a mini-robot to Enceladus, allowing the robot to burrow beneath the icy crust to search for extraterrestrial organisms.

However, the new study led by planetary scientist Régis Ferrière from the University of Arizona (USA)—a frequent collaborator with NASA on missions—reveals that an orbital spacecraft alone is sufficient.

An orbital mission would be less costly, easier to implement, and could materialize much sooner than the planned lander and accompanying robot. The new spacecraft would need to be equipped with enhanced tools compared to Cassini but would perform similar tasks, such as sampling gas plumes, or it could even land for direct sampling without the need for a robot.

The reason is that the excess methane detected by Cassini was enough to evoke images of unique ecosystems existing at hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor—much like the hydrothermal systems found at the bottom of the ocean areas near Hawaii or Antarctica, which are teeming with life despite darkness and high pressure.

The organisms living there are primarily simple bacteria known as methanogens, which produce energy without sunlight.

Methanogens convert dihydrogen and CO2 to harvest energy, releasing methane as a byproduct. Therefore, further analysis of the methane plumes emitted from the subsurface ocean would be sufficient to assess the biosphere of Enceladus. Additionally, these gas plumes could carry cells of extraterrestrial organisms, and our task would be to use advanced analytical tools to capture them.

These specific organic molecules would serve as evidence to confirm or refute the belief in a rich biosphere on Enceladus that NASA has nurtured for so long.