From ancient scrolls to paintings from the golden age of Dutch art, technology is uncovering new clues about artworks.

The history of painting has always contained masterpieces that were lost or destroyed. Some paintings were even created over existing works, a fact that was only discovered centuries later, thanks to technological advancements.

After the catastrophic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, which buried the city of Pompeii and its surroundings, many libraries containing ancient books turned to ash, and the wall paintings were too fragile to excavate.

One of the masterpieces by the Dutch master Rembrandt – The Night Watch (1642), was trimmed to fit through the door of the Amsterdam city hall in 1715. For a long time, art researchers accepted the reality that these losses would be permanent.

Few people know that Rembrandt’s The Night Watch (currently displayed at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam) was trimmed on both sides. (Photo: Rijksmuseum).

Searching for Hidden Details

In recent years, with the help of advancing technology, there has been a wave of efforts to restore parts or even entire lost artworks.

Similar to AI, machine learning has infiltrated many aspects of daily life. Now, this technology is helping to revive precious art artifacts that have faded over time.

Throughout history, it has not been uncommon for artists to paint over older works. This can be discovered when a painting is placed under X-ray examination.

A project named Oxia Palus has recently garnered attention. Founded by PhD candidates George Cann and Anthony Bourached, this project aims to resurrect original paintings hidden beneath layers of other artworks.

Oxia Palus began publishing its first images in 2019, using AI to identify the original colors and textures of the paintings that were painted over. Subsequently, the two researchers employed 3D technology to reconstruct the original artworks. These reconstructed paintings will be sold as prints.

“I think many people are interested in this because they enjoy new things. It would be wonderful to behold these masterpieces, as they exist but were previously invisible, because no one wanted to scrape off the top layer of a painting worth millions of pounds,” Bourached shared.

George Cann and Anthony Bourached also want to remind everyone that using technology to restore paintings is not a simple task.

“Articles that draw attention to the topic of ‘AI technology restoring a painting’ make it seem as if we just need to press a button and everything will be done,” Bourached added.

According to Bourached, this can create the impression that scientists are handing over complete control to machines, while in reality, there is a significant amount of human effort involved in the process.

Specifically, team members must collect data from other works by the artist to understand the author’s painting style, then filter the results from the X-ray scans to eliminate unnecessary elements.

According to Cann, the final images from the X-ray scans will be “our interpretation of what lies beneath.” The two scientists acknowledge that this process is not truly meticulous, as they view it as a casual experiment rather than a meticulously funded project.

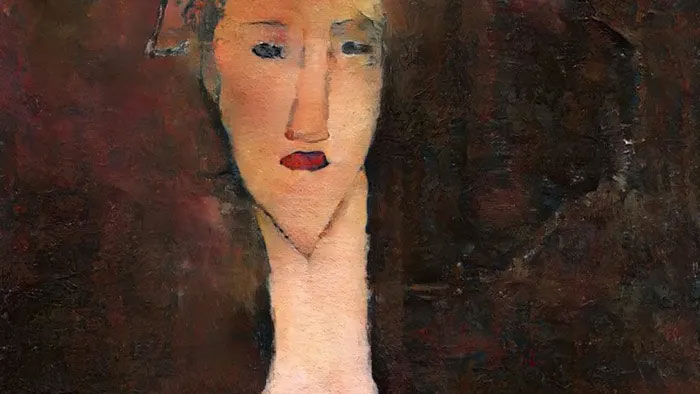

Image of a woman hidden beneath the painting Portrait of a Girl (1917) by Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani. (Photo: Oxia Palus).

“One thing we want to emphasize is that while this is a relatively naive approach, it is entirely feasible. I hope others will embrace this nascent field and do even better things,” Bourached shared.

During their work, Cann and Bourached’s team faced a significant barrier. The use of X-rays to scan paintings—first utilized in the 19th century—proved ineffective in gathering information.

The Power of Technology

Art conservators sometimes need to take direct samples from paintings to learn about the types of materials and components of the pigments used. However, modern scanning technologies allow them to collect all this data without touching the painting.

Five years ago, the National Gallery in London purchased a modern scanner capable of collecting extensive data about a painting. The issue here is that the data obtained is so vast that most cultural institutions lack the resources to analyze it.

To overcome this bottleneck, cultural organizations like the National Gallery have now partnered with universities to access advanced computing and the expertise of scientists.

In a project called Art Through the ICT Lens (ARTIC), the National Gallery collaborated with University College London (UCL) and Imperial College London to analyze the painting Dona Isabel de Porcel by Spanish master Francisco de Goya, painted in 1805.

This work by Goya depicts a woman wearing a black shawl. However, in 1980, when scanned, a second mysterious portrait of a man in a coat was discovered beneath this painting.

To create a clearer image of this hidden painting, researchers had to place Goya’s work under the scanner multiple times, combining different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Initially, this process had to be done manually, but now it is fully automated.

UCL researchers, led by Dr. Miguel Rodrigues, previously participated in a similar project to restore the Ghent Altarpiece (1432) by Dutch master Jan van Eyck.

While some research efforts help us understand what lies beneath paintings, others assist scientists in restoring what has been lost. In 2011, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam invited the public to view a complete recreation of Rembrandt’s The Night Watch.

The original version of The Night Watch fully restored using AI technology. (Photo: Rijksmuseum).

Fortunately for us, before this enormous painting was trimmed to fit into the Amsterdam city hall, a lesser-known artist named Gerrit Lundens made a complete copy of the original. However, there are still very slight differences between the painting styles of the two artists, and scientists had to guide the algorithm to reconstruct the missing parts of the painting in the style of Rembrandt.

“The algorithm even mimics the small cracks in the painting, so I would say it is based on scientific foundations as much as possible. That doesn’t mean it’s perfect; technology will always improve,” shared Rob Erdmann, a senior scientist at the Rijksmuseum.