Trinitite is a glass-like material with a unique structure, typically gray, green, or red, that only forms as a result of a nuclear explosion.

To create trinitite, one only needs a bucket of sand and the intense heat of a nuclear weapon, as reported by IFL Science on March 25. Scientists began to take notice of this special glass after the first atomic bombs were dropped during the final stages of World War II. Experts later discovered that this material is even stranger than they had previously thought.

On July 16, 1945, the U.S. military conducted the world’s first nuclear bomb test in the New Mexico desert, codenamed “Trinity.”

In an instant, a device containing radioactive plutonium encased in a metallic shell known as “Gadget” exploded, creating a massive fireball that soared into the sky, vaporizing everything it touched. The test was a success.

However, this experiment was not only destructive; it also gave rise to a new substance.

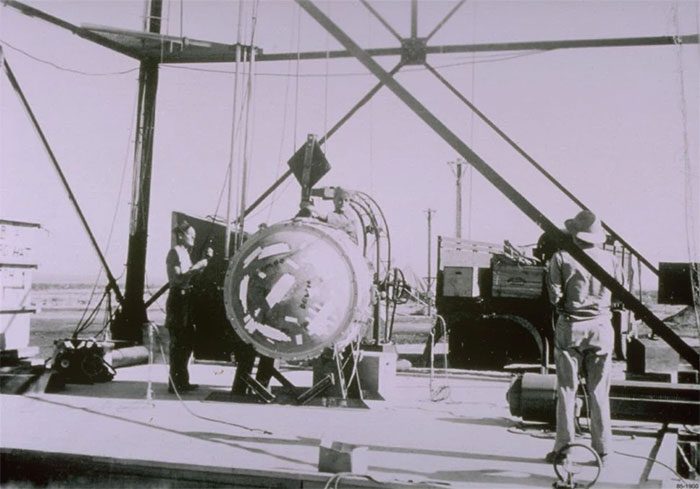

Researchers beside the “Gadget” metal sphere, preparing for the world’s first nuclear explosion (Photo: Live Science).

In a study published in the “Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences” on June 1, researchers reported the discovery of unusual crystals known as “quasicrystals.” These were found within rocks at the Trinity site.

Quasicrystals are a form of ordered structure that lacks periodicity.

These strange crystals lack the symmetry typically seen in known crystals; they are usually found in meteorites from the early solar system and are believed to only form under the extreme temperatures and pressures of the universe’s most powerful explosions.

The Structure of this Special Crystal

“To understand other countries’ nuclear weapons, we need to have a clear understanding of their nuclear testing programs. We often analyze debris and radioactive gases to understand how the weapons are made or what materials they contain… A type of crystal has formed at the site of the nuclear explosion…” the study’s author stated.

When the “Gadget” exploded, it created a fireball hotter than the sun. The heat and force of this explosion were so intense that the surrounding metal and sand melted together, forming a new type of crystal, later named Trinitite.

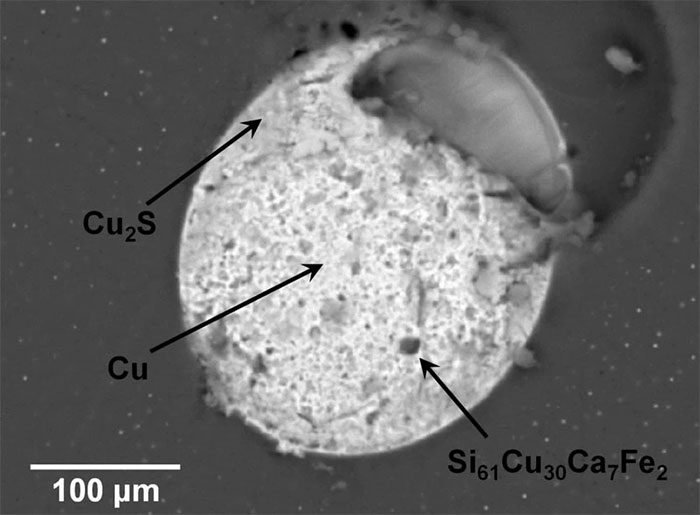

A “color spot” within a Trinitite sample containing an unprecedented quasicrystal. (Photo: Live Science).

Quasicrystals were a theory mentioned since 1984, describing a structure that is both ordered and disordered, alternating between the two states. However, scientists later proved that such a structure could not exist on Earth, as it requires a thermodynamic shock from a high-velocity impact event that is hard to imagine.

Using techniques like electron microscopy and X-ray diffraction, they observed six red trinitite samples. While trinitite can also appear green like glass, the red variety is considerably rarer, as it results from the accidental convergence of materials from thin copper wires during the explosion.

The first unique quasicrystal discovered in the world – (Photo: University of Florence)

Ultimately, they discovered a treasure: a tiny silicon-copper-calcium-iron grain with 20 facets and rotational symmetry that is five times greater than what is possible in ordinary crystals.

It possesses that magical combination—alternating between order and disorder. It is a quasicrystal. Scientists understand where it formed and what it is, but they still do not know exactly how it came to be.

Recent findings show that trinitite has an extremely unusual atomic structure containing “forbidden” quasicrystals. A typical crystal is a material with atoms arranged symmetrically in a repeating pattern. In contrast, quasicrystals have their atoms arranged in an ordered manner, but the pattern does not repeat. This creates a non-repeating and asymmetrical atomic structure, different from typical crystals and termed “forbidden symmetry.”

Experts note that quasicrystals can form from meteorite events and in laboratories, but it seems that a nuclear explosion also generates sufficient force. When Israeli materials scientist Daniel Shechtman first identified quasicrystals in the 1980s, he faced criticism and ridicule. However, this discovery eventually earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011.