This mystery has lingered in the minds of the people of Oregon, USA, for over 100 years. Furthermore, there has been much speculation about the existence of this meteorite, especially since it has been missing since the 19th century.

The story begins with the U.S. Department of the Interior’s decision to hire a man named John Evans to conduct a survey in Oregon.

There is much speculation surrounding this mysterious meteorite. (Illustrative image).

Initially, John Evans was tasked with conducting a geological survey of Southwestern Oregon. It was here that he became famous, and the mysteries surrounding this meteorite began to emerge.

John Evans was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1812. He was the son of Richard Evans, a Justice of the New Hampshire Supreme Court. He attended medical school at St. Louis College and earned his medical degree there.

In 1835, he married Sarah Zane Mills. Although he was a medical doctor, John Evans also had a strong interest in geology and had professional research experience as a geologist at the Smithsonian Institution. He was frequently honored for his geological studies, and in 1854, he was elected as a member of the American Academy of Natural Sciences.

John was appointed as an assistant to the renowned geologist, Dr. David Dale Owen, to help him with a project in Iowa, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. John was expected to examine the boundaries of Tertiary formations and Cretaceous formations west of Missouri.

While doing this, he impressed Owen with his discovery of coal seams near Fort Berthold, a valuable resource for the area. Evans continued to impress his colleagues with subsequent missions and was appointed to succeed Owen in the Oregon region. It was here that he made his significant discovery.

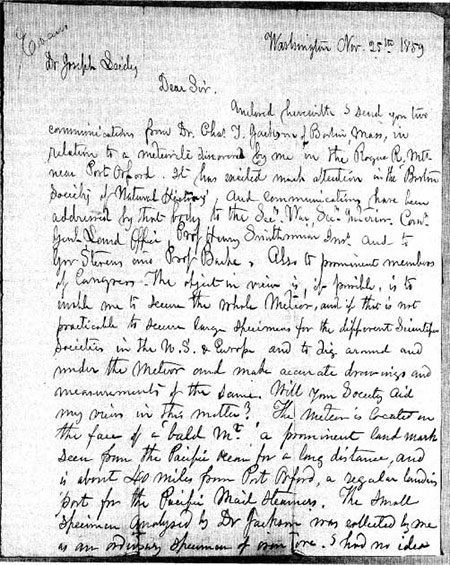

John Evans’ 1859 letter discussing the discovery of the meteorite.

In a report, Evans discussed a remarkable meteorite. He claimed that during the event known as the “Indian War”, he climbed a mountain called Bald Mountain (located within the Rogue River range about 56-64 kilometers from Port Orford) and discovered a mysterious meteorite.

He brought back a piece of this meteorite and sent it to a laboratory for study. When the results came back, they revealed that it was indeed a meteorite. This was an exciting discovery for science at the time. However, according to Evans’ notes, this meteorite was very large, making it difficult to transport the entire meteorite back to the laboratory.

Additionally, due to the rugged terrain, moving the meteorite could only be accomplished using local pack animals. Evans estimated that transporting the meteorite would cost about $3,000 at that time.

As a result, the meteorite was never moved, and its existence was known only through John Evans’ notes.

Evans’ field notes did not contain maps or mention specific locations of the meteorite. (Illustrative image)

Reports about this meteorite quickly spread across the United States, with some articles even claiming it weighed around 10 tons. Many subsequent expeditions were planned under Evans’ leadership, but unfortunately, none were carried out as Evans died of pneumonia in 1861.

With the only witness who could confirm the meteorite’s location deceased and insufficient information in his remaining notes, subsequent expeditions to trace the meteorite’s path faced unexpected failures.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the Smithsonian Institution showed great interest in this meteorite, organizing several searches based on Evans’ route. However, this colossal meteorite remained undiscovered once again.

Evans’ field notes also lacked maps or mentions of specific locations. Therefore, the expeditions could not accurately determine the directions that Evans had previously taken.

This colossal meteorite has not been discovered once again. (Illustrative image).

In the 1920s, the Boston Society conducted a review of the meteorite samples that John Evans had brought back earlier. Experts examined them and subjected them to various rigorous tests.

Edward Henderson, who was in charge of researching the meteorite samples at that time, concluded that while he could confirm that the rocks actually originated from a meteorite, he was uncertain whether they came from the giant meteorite in Oregon. Henderson spent many years searching for this colossal meteorite but to no avail.

The quest for the Oregon meteorite continued, and by 1964, it was reluctantly concluded that this meteorite might not exist at all.

In the 1990s, historian Howard Plotkin conducted extensive research by thoroughly examining historical records. He collaborated with metallurgists Vagn Buchwald and Roy Clarke, Henderson’s colleagues at the Smithsonian Institution, to investigate the existence of the Oregon meteorite.

Clarke and Buchwald concluded that the meteorite samples that Evans brought back actually belonged to a meteorite field located in the Atacama Desert on the coast of Chile. Furthermore, it is very likely that Evans deceived the entire nation about his mysterious discovery.

Evans fell into financial distress in the 1850s. This may have been his motive to try to deceive the world. Perhaps he hoped to gain fame and secure government funding as a renowned geologist.