Living at depths of thousands of meters and rarely surfacing, the behavior and reproductive methods of the Antarctic giant squid remain a significant mystery for researchers.

Simulation of the Antarctic giant squid living in deep-sea waters. (Video: Te Papa Museum)

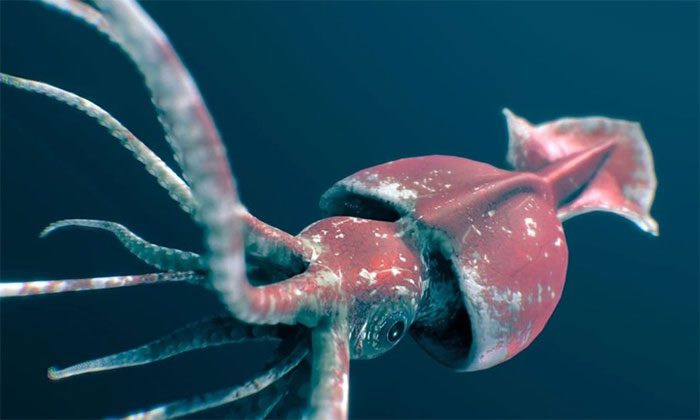

While the giant squid is a monster in terms of size, it has an even larger and more elusive relative known as the Antarctic giant squid. The first evidence of the Antarctic giant squid came from tentacles found in the stomach of a sperm whale in 1925. It wasn’t until 1981 that researchers caught the first intact specimen of the Antarctic giant squid, a nearly mature female. This creature is scientifically named Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, characterized by its sharp hooks on its arms and tentacles. In contrast, the tentacles of the giant squid have suckers with small teeth, according to ThoughtCo.

Although the giant squid can be longer than the Antarctic giant squid, the latter has a longer mantle, a wider body, and a greater mass than its relative. The size of the Antarctic giant squid is about 12 – 14 meters long and can weigh up to 750 kg. This makes them the largest invertebrates on Earth. Their massive size is also reflected in their eyes and beak. The beak of the Antarctic giant squid is the largest among squids, while its eyes can have a diameter of 30 – 40 cm, the largest in the animal kingdom.

Photographs of the Antarctic giant squid are extremely rare because they live in deep-sea environments and their bodies are not suitable for surfacing. The few images available show that before being brought to the surface, they have a reddish skin and their mantle is puffed up. A specimen is displayed at the Te Papa Museum in Wellington, New Zealand, but it does not exhibit the natural colors or size of a living squid.

Very few people have observed the Antarctic giant squid in its natural habitat.

The Antarctic giant squid is found in the cold waters of the Southern Ocean. Their habitat ranges from the northern Antarctic to the southern coasts of Africa, South America, and New Zealand. Based on the depths at which they are caught, scientists have determined that immature squids live at depths of one kilometer, while adults operate at depths of at least 2.2 km. Therefore, the behavior of this squid species remains a mystery to researchers.

The Antarctic giant squid does not prey on whales; instead, they are preyed upon by whales. Some species of sperm whales bear scars that appear to be caused by the hooks from the Antarctic giant squid’s tentacles, which may serve as a form of defense. When researchers examined the stomach contents of sperm whales, 14% of the beaks found were from Antarctic giant squids. Other animals that feed on them include beaked whales, elephant seals, Patagonian toothfish, albatrosses, and sleeper sharks. However, most of these predators only consume immature squids. The beaks of mature squids have only been found in the stomachs of sperm whales and sleeper sharks.

Very few scientists or fishermen have observed the Antarctic giant squid in its natural habitat. Due to their size, depth of living, and body shape, researchers believe they are ambush predators, using their large eyes to track passing prey before striking with their beaks. They have not been seen swimming in schools, suggesting they may be solitary hunters. Scientists have also not witnessed the mating and reproductive processes of the Antarctic giant squid. What is known is that they exhibit sexual dimorphism. Mature females are larger than males and have ovaries containing thousands of eggs. It is possible that the Antarctic giant squid lays its eggs within a floating gel mass.

Currently, the Antarctic giant squid is classified as “Least Concern” in terms of conservation. They are not considered an endangered species, although researchers have not been able to estimate the population of these squids. Encounters between humans and both giant squid species are extremely rare. Both species are incapable of sinking boats and attacking sailors. They prefer to live at great depths. Mature Antarctic giant squids typically do not surface near the water’s surface because warm temperatures affect their buoyancy and reduce oxygen in their blood.