In 1528, King Henry VIII of England slept in a different bed each night, but not in the way you might think.

It wasn’t the women that drove King Henry VIII to move almost daily that summer; it was the fear of a mysterious disease. The king was genuinely terrified of the sweating sickness, a deadly epidemic that has largely been forgotten today.

King Henry VIII of England feared the sweating sickness throughout his reign. (Photo: History)

Nevertheless, some scientists remain fascinated by this mysterious illness, which swept through Europe multiple times during the Tudor period (the golden reign of King Henry Tudor, or Henry VII). Since 1485, five outbreaks had ravaged England, Germany, and other European countries. Yet, the origins of the disease and even its name remain unclear to this day.

There was justifiable fear surrounding the sweating sickness. It struck without warning and seemed unstoppable. Those afflicted suddenly felt a sense of dread, followed by headaches, neck pain, weakness, and profuse sweating. Victims experienced fever, rapid heart rates, and dehydration. Within 3 to 18 hours, 30-50% of those infected had died.

It is unclear who was the first to contract the sweating sickness, but some historians believe that the disease was brought to England by mercenaries hired by Henry VIII’s father to secure the throne for him and his son. This power grab ended the Wars of the Roses (the civil war for the English crown) in 1487.

Illustration of a person suffering from sweating sickness.

The sweating sickness quickly became an epidemic in the region. It was described as “a new type of illness, causing pain and suffering, with symptoms that anyone prior to that time had never heard of” – wrote Richard Grafton, the King’s printer.

However, that record is not entirely accurate. England had previously survived the most terrifying plague in history. From 1346 to 1353, the Black Death wiped out 60% of the world’s population, killing over 20 million people in Europe alone. But the sweating sickness seemed unrelated to this pandemic. It had no skin symptoms and appeared randomly in different locations, often following periods of prolonged rain or flooding, and typically targeted either the very wealthy or the very poor.

At that time, people had no way to know how the sweating sickness attacked or spread. Nonetheless, that did not stop doctors from trying to understand it, and the strange disease made one man named John Kays famous. He viewed the illness as an opportunity – especially since it seemed to frequently attack wealthy nobles. Kays adopted a more impressive name, Johannus Caius, and began treating wealthy Englishmen who were terrified and paranoid about the disease.

John Caius (1510 – 1573), English physician and scholar – painted around 1560. (Photo: Getty Images)

Caius also found another way to profit from the sweating sickness: writing about it. In 1552, he published “The Sweating Sickness: A Remedy for the Illness Commonly Known as the Sweating Sickness.”

This is regarded as a classic medical text, offering the physician’s observations on symptoms, prevention, and cures. With the medical knowledge of his time, Caius advised people to avoid fog, not eat spoiled fruit, and exercise regularly. He recommended that those who fell ill should drink herbal concoctions, sweat as much as possible, and avoid going outdoors.

Biomedical researcher Derek Gatherer wrote: “Although most of Caius’s patients ultimately died, he still became wealthy enough to create a substantial endowment for his old college at Cambridge.” Today, a college in Cambridge still bears Caius’s name.

Caius and other doctors were unable to explain or prevent the sweating sickness. However, the fact that royal members rushed to doctors for help speaks volumes about the impact of the epidemic.

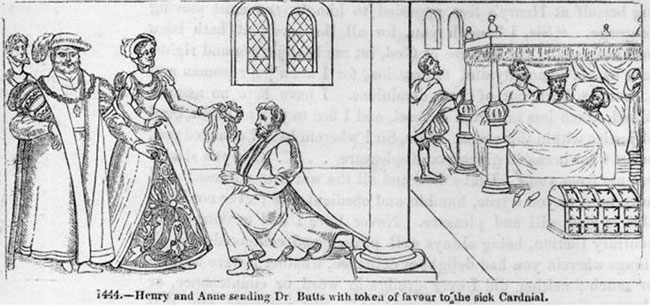

King Henry VIII lived in constant fear of contracting the disease throughout his reign. Many of his courtiers became victims of the mysterious illness, including his advisor, Cardinal Wolsey, who was fortunate to survive, and Arthur, the king’s brother, who died from the disease.

Thomas More, an advisor to Henry VIII, wrote: “One feels safer on the battlefield than in the city.”

King Henry VIII and Queen Anne Boleyn sending court physician Butts to visit Cardinal Wolsey, who was suffering from the sweating sickness. (Photo: Getty Images)

The sweating sickness ended as abruptly as it began. The last outbreak occurred in 1551. About 150 years later, a variant known as “Picardy Sweat” emerged in France, but neither returned with a vengeance.

This has made it difficult for modern scientists and historians to study the disease. They have to rely on period data and rudimentary public health information to reconstruct the sweating sickness outbreaks.

Ultimately, scientists have yet to definitively identify what the sweating sickness really was. Some believe it was a type of hantavirus causing a rare illness. Others suspect it was symptoms of influenza, food poisoning, or relapsing fever.

Regardless of the cause, the sweating sickness left its mark. When the great playwright William Shakespeare wrote the play “Henry IV, Part 2” in 1600, half a century after the last outbreak in England, one of his most famous characters, Falstaff, died from “the sweating sickness.”