Since their discovery, the origins of hundreds of mummies buried in boats in the harsh desert of the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang have remained a mystery that puzzles researchers.

Unearthed in the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang during the 1990s, the mummies and their accompanying garments remain remarkably intact, despite dating back as far as 4,000 years. Natural preservation due to the dry, hot air of the desert has allowed most of the mummies to retain their facial features and hair color. Their Western appearance, woolen clothing, along with cheese, wheat, and millet found in their graves, indicate they were long-distance herders from the steppes of Western Asia or farmers migrating from the mountains and oases of Central Asia.

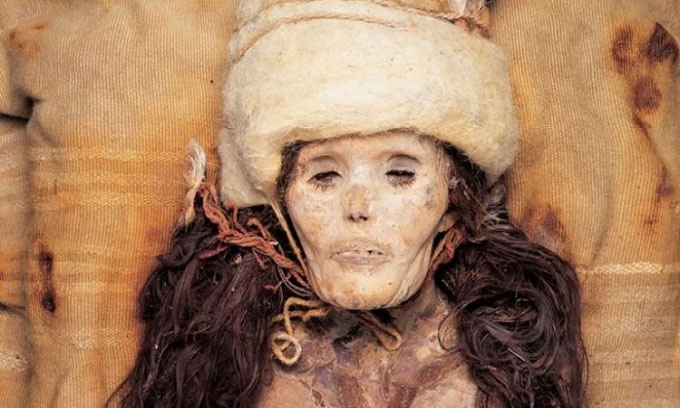

Hundreds of mummies scattered across boat graves in the Tarim Basin desert. (Photo: Xinjiang University)

However, a research team comprising scientists from China, Europe, and America analyzed the DNA of 13 mummies, sequencing their genomes for the first time and making a new discovery. Their analysis revealed that these mummies were not newcomers to the area but rather local residents, descendants of an ancient Asian population from the Ice Age.

“The mummies have long attracted the interest of both researchers and the public since their discovery. We found evidence that they were a local community with high genetic isolation. However, they appeared to be very open to adopting new ideas and technologies from nearby herders and farmers while developing a distinctive cultural identity not found in any other community,” said Christina Warinner, an associate professor of anthropology at Harvard University and a co-author of the study published on October 27 in the journal Nature.

The dry, hot conditions of the desert helped preserve the mummies for thousands of years. (Photo: Xinjiang University)

The research team examined genetic information from the oldest mummies in the Tarim Basin, dating from 3,700 to 4,100 years ago, along with sequenced genomes from the remains of five individuals in the Dzungarian Basin, north of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Dating back 4,800 to 5,000 years, these are the oldest remains in the area. Ancient DNA can provide compelling evidence of human migration during a period when written records are very scarce, according to Vagheesh Narasimhan, an assistant professor at the University of Texas, Austin.

The study found that the mummies in the Tarim Basin showed no signs of admixture with other contemporary populations. The mummies are direct descendants of a group that once had a wide distribution during the Ice Age but largely vanished around 10,000 years ago. Traces of this hunter-gatherer group only exist in the genomes of present-day people, with the highest percentages found among indigenous Siberians and populations in the Americas.

However, the study only examined mummies from one area. Researchers are uncertain whether broader genomic sequencing in the Tarim Basin would yield different results. Although initial findings suggest that the mummies lived along the peninsula in the desert, the research team is unclear why they were buried in boats covered with animal hides and with paddles placed at the bow of the boats.