From the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, brilliant minds are harboring extraordinary thoughts, hoping to extend humanity’s reach beyond the Solar System.

On October 31, 1936, a group of six self-proclaimed Rocket Boys narrowly escaped death in a fire while attempting to break free from Earth’s gravitational pull. At the foot of the San Gabriel Mountains in California, these curious friends experimented with an alcohol-powered rocket engine; they aimed to demonstrate that rocket engines could enable human spaceflight at a time when society had yet to fully trust commercial aircraft. The plan went awry when the oxygen line caught fire, sending sparks flying dangerously.

The bold ideas of the Rocket Boys caught the attention of aerodynamics expert Theodore von Karman, who had previously collaborated with two of the six daring individuals while they were studying at Caltech. In a prime location not far from the site of the initial experiments, von Karman established another area where the Rocket Boys could continue their trials.

By 1943, this site became the foundation for the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), with Theodore von Karman serving as its first director. To date, JPL has developed into one of NASA’s leading research branches, employing thousands of staff, yet the laboratory has maintained its original mission. Experts diligently test the limits of space travel every day, striving to apply scientific concepts that dance between reality and fiction.

Over the years, JPL has achieved many milestones. In the early 1970s, the laboratory’s engineers successfully created the Pioneer 10, the first spacecraft capable of reaching speeds sufficient to escape the Solar System. A few years later, they successfully launched the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecrafts, some of the fastest artificial objects in history, which are now traveling toward interstellar space.

In just two decades, from the dawn of the Space Age to the launch of the two Voyagers, rocket design experts doubled the speed of spacecraft. However, since then, the aerospace industry has only seen one spacecraft follow Voyager out of the Solar System—the New Horizons probe, which launched in 2006; no other probe has achieved such high speeds. JPL experts are restless, determined to find a new leap in space travel technology.

Regardless of the new efforts, experts generally agree that the scale of the “Solar System” has become limiting. This is the moment humanity needs to look towards planets beyond our local celestial bodies, reaching for distant stars.

John Brophy, a propulsion engineer at JPL, is developing an unusual engine technology that could increase the speed of space travel by tenfold. Leon Alkalai, another space mission architect, envisions an interstellar journey that begins with a dive towards the Sun. Another scientist at JPL, Slava Turyshev, is sketching out a telescope system that would allow us to observe Earth-like planets in detail without needing to visit them.

All these ideas are long-term plans, but if just one succeeds, the applications would be countless. The Rocket Boys and their descendants have turned humanity into a space-faring species; contemporary researchers at JPL will help humanity venture into the stars.

Ion Thrusters

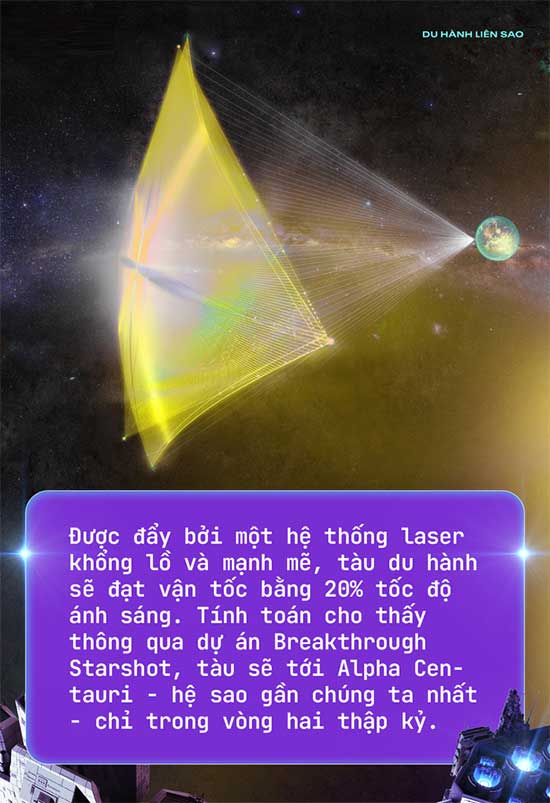

Researcher Brophy’s inspiration comes from Breakthrough Starshot, a project announced in 2016 by the late theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking and Russian billionaire Yuri Milner. The ultimate goal of the project is a large laser array spanning kilometers that could propel a small spacecraft to incredible speeds.

Brophy is skeptical about the feasibility of Breakthrough Starshot, but the engineering behind it piques his curiosity. “JPL encourages its personnel to think outside the box, making my bizarre ideas even stranger over time,” Brophy reveals. While he believes the practicality of the Breakthrough Starshot project is unrealistic, he wonders if the concept could be scaled down to a level where near-futuristic technology could accommodate it.

The idea of using lasers to propel spacecraft inspired Brophy to seek a similar solution because it could resolve the “rocket equation” that links a spacecraft’s motion to the amount of fuel it carries. This opens up a series of tricky problems, as the mathematical equation is a barrier for all space travel systems: moving faster requires more fuel, but more fuel increases mass; greater mass requires more thrust, which means more fuel. The cycle continues endlessly.

Fuel—an essential component in chemical propulsion systems—is also what limits our ability to travel far. For instance, the rocket system that propelled the Voyager probes (which weigh just over 800 kg) weighed over 600 tons, with fuel accounting for the majority of this mass.

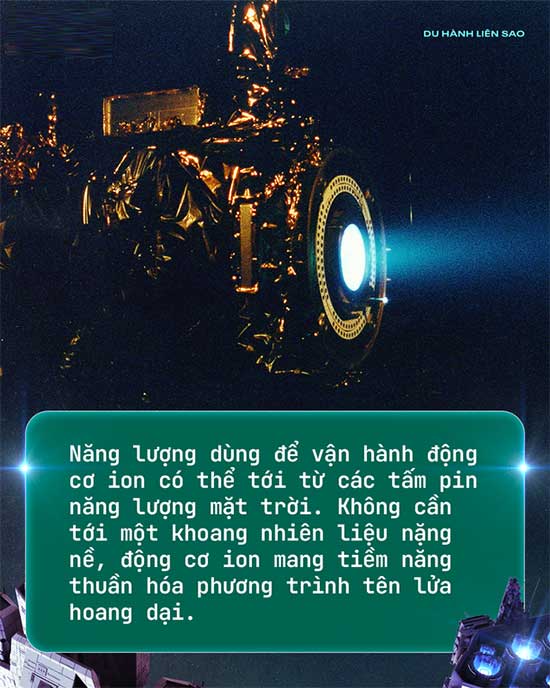

Since graduating in the 1970s, Brophy has researched and developed a propulsion system known as ion propulsion. An ion thruster uses electrical energy to shoot positively charged atoms (ions) at high speeds. Each atom produces a small amount of thrust, but the ability to accumulate force means ion engines can propel spacecraft faster than chemical propulsion engines.

Ion engines still have their limitations. The farther one flies from the Sun, the less effective the solar panels become. Increasing the size of the panels could remedy this, but larger size means increased mass, and the rocket equation continues to haunt the spacecraft.

An ion engine does not produce enough thrust to escape Earth’s gravity. Even in a vacuum, an ion engine still takes considerable time to reach maximum velocity. Brophy is all too aware of these limitations, having designed the ion engine for the Dawn spacecraft, which recently completed an 11-year mission exploring the asteroid Vesta and the dwarf planet Ceres. Even with solar panels spanning 20 meters, Dawn took four days to accelerate from 0 to 100 km/h.

While Brophy continues to weigh the effectiveness of engines against insufficient solar power, the Breakthrough Starshot project launched into public view. This prompted the seasoned researcher to shift his thinking: could he use extremely powerful lasers to replace the dimming lights of distance? With a sufficiently powerful laser system, the ion engine could operate more vigorously without needing to carry an oversized solar panel.

In his laboratory, Brophy has assembled a prototype of a high-performance ion engine full of potential. The device uses lithium ions, which are lighter than the xenon ions used by Dawn, meaning this new device would require less energy to propel the spacecraft at higher speeds.

The new engine will operate at a voltage of 6,000 volts, six times the level at which Dawn operated in the past. “The performance of this device will be truly astounding if we have a laser system backing it,” he asserts.

However, that laser generator does not currently exist. Despite scaling down the Starshot model significantly, Brophy still envisions a laser system in space capable of 100 megawatts, producing energy 100 times that generated daily by the International Space Station (ISS), which would need to accurately target a spacecraft traveling at high speed.

“We are not sure how to make that happen,” Brophy admits. If realized, it would be the most complex extraterrestrial engineering project ever undertaken. But once successful, this powerful laser array could be reused for many missions, serving as a multifunctional system to assist in propelling spacecraft.

For example, Brophy describes a spacecraft powered by lithium-ion batteries with a wingspan of 90 meters covered in solar panels, which would supply energy to the ion thruster he is developing at JPL. The laser would illuminate the solar panels with brightness hundreds of times greater than sunlight; it would enable an ion engine to easily travel from Earth to Pluto, a distance of about 5 billion km. With the initial acceleration, the spacecraft could travel an additional 5 billion km within one to two years after reaching Pluto.

At this speed, a spacecraft could quickly explore the hazy region where comets originate or begin the journey to study the hypothetical ninth planet. In short, the laser array would help humanity reach into nearly every corner of the Solar System.

“It’s like having just bought a brand new hammer; I will run around looking for any nail that can be hammered,” Mr. Brophy dreamily thought about a beautiful future. “We have a long list of missions you could undertake if you could fly that fast.”

Giant “Rubber Band” Launching Spaceships Far Away

At JPL, another brilliant mind sees potential in the “science fiction” laser system of Breakthrough Starshot. Mr. Alkalai, who shapes the development direction for new missions at the Engineering and Science Directorate at JPL, also possesses a visionary outlook of a man passionate about new horizons. He believes that the Starshot project is on the right track, but it is moving too hastily.

“We are still far from having the modern technology needed to design a mission to another star. We need to start with baby steps,” he said.

He envisions a way to take that first step. Although we cannot yet visit other stars, we can still send probes to collect samples from interstellar space, which includes the remnants of gases and cosmic dust floating between the stars.

“I am very interested in understanding the materials beyond the Solar System. After all, we originated from them. Life emerged from primordial dust clouds,” Mr. Alkalai stated. “We know that there is organic matter within them, but what kind is it? What is its density? Is there water molecules in there? Those are the big [pieces of knowledge] that need to be understood.”

The region between the stars remains a mystery because we have yet to reach it. Solar winds, a stream of particles emitted from the central star of the Solar System, push the materials we need to study away. If we can reach the region of space beyond the influence of the Sun, we will be able to collect the “pure” samples of the Milky Way for the first time.

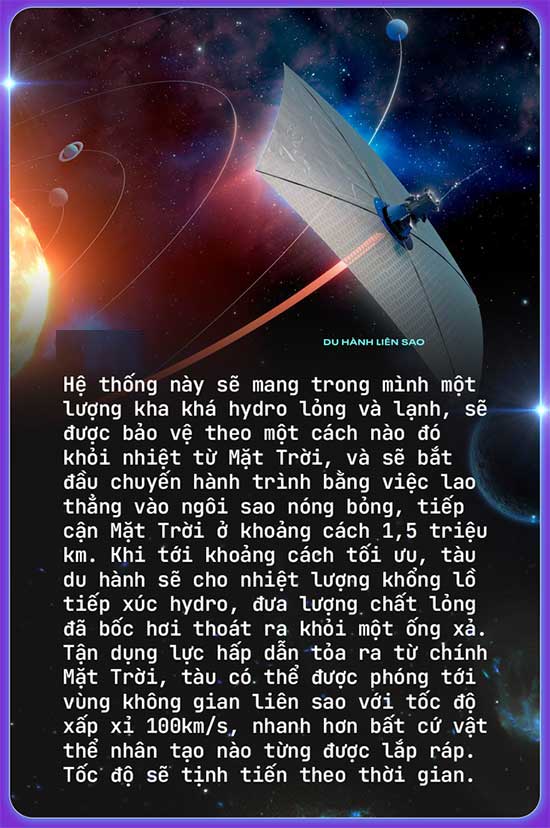

Mr. Alkalai looks forward to the day he can see valuable samples with his own eyes. In his 60s, he cannot expect the giant laser array of Breakthrough Starshot to come to fruition. Instead, he proposes a simpler yet unproven technology known as solar thermal rockets.

“It’s challenging, but we are modeling the related physical factors,” Mr. Alkalai explained. He hopes to soon test some components of the solar thermal rocket system and turn those designs into a complete mission within the next decade. About ten years after launch, the device would reach interstellar space.

In addition to collecting samples from the galaxy, the spacecraft will record the Sun’s influence on the distant void, studying the structural dust within the Solar System. A smooth journey will allow the probe to conveniently pass by a certain planet.

Mr. Alkalai calls this trip “unlike any project we have undertaken in the past.”

Peeking Instead of Visiting

Concepts like solar thermal rockets or laser-ion engines are impressive, but they still reside firmly in the realm of science fiction. The distance between the Solar System and interstellar space remains daunting with current technology. However, this does not deter researcher Turyshev, who is designing a “virtual” mission to help us reach another star.

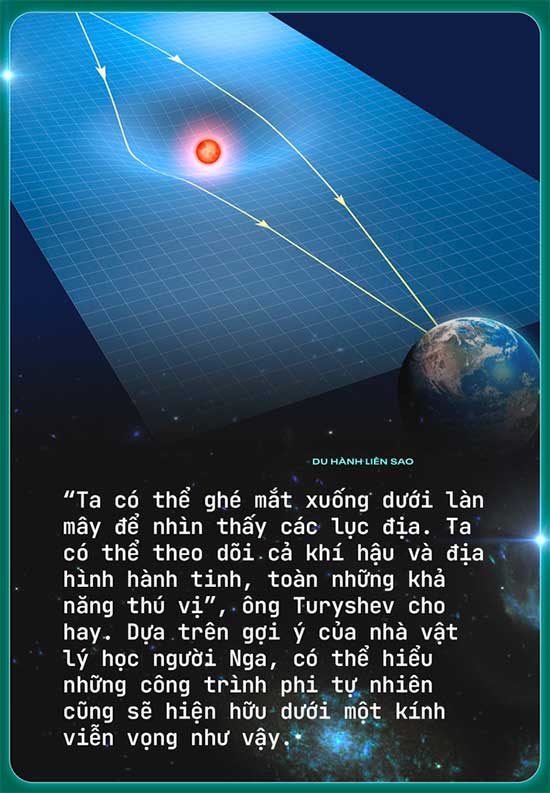

He is nurturing a telescope project based on a theoretical method known as “the solar gravitational lens (SGL)”.

A telescope positioned to take advantage of the SGL would witness a beautiful phenomenon. When looking towards the Sun, the telescope would see light from objects behind it being stretched, forming a ring surrounding the Sun. This bright ring is known as the Einstein Ring (also referred to as the Chwolson Ring, named after Russian physicist Orest Khvolson), which appears due to the gravitational light-bending effect of the Sun.

According to Mr. Turyshev, a telescope that can utilize the SGL would focus on specific points on the Einstein Ring, reconstructing images of distant places—potentially stars, exoplanets in other star systems, galaxies—into a high-resolution image.

Theoretically, the image could be that clear. An image with a resolution of 1000×1000 pixels would be clear enough to contain data about an object 15 km wide located 100 light-years away from the telescope (approximately 950 trillion kilometers).

The mission would require equipment the size of the Hubble Space Telescope, surviving a planned journey of 547 astronomical units, equivalent to 82 billion kilometers, which is 55,000 times the distance between the James Webb Space Telescope and Earth. As proposed by Mr. Turyshev, the arduous trip would last 17 years, guided by an artificial intelligence system.

Above all, they will need a research target—a planet worth billions of dollars of investment and decades of research and development. With the motto “start with the easy tasks,” NASA is currently looking for an Earth-sized exoplanet capable of supporting life.

“Ultimately, to see life on an exoplanet, we will have to visit it. But an observational mission will allow us to study potential targets long before many decades, even centuries,” Mr. Turyshev enthusiastically proposed.

This journey, which could change human perception, will demand more than the success of ion engines and “solar rubber bands.” It is a distant destination, but at least we have valuable experiences in deploying telescopes into the cold void.

The upcoming achievements announced by the James Webb Space Telescope development team will fuel Mr. Turyshev’s project while opening up new viable research directions. After all, seeing is believing, and when we can see and measure accurately, then seeing will lead to visiting.