A strange white structure retrieved from the depths of the ocean off the coast of Oregon, USA, promises to guide scientists in their search for life on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

A collaborative study among several academic institutions in the United States, supported by NASA’s Astrobiology Program, has identified a previously unknown type of protein that plays a crucial role in stabilizing sediment structures.

This protein belongs to deep-sea bacteria capable of encoding genes different from any previously known genes in surface-dwelling organisms, according to Professor Jennifer Glass from the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, a member of the research team.

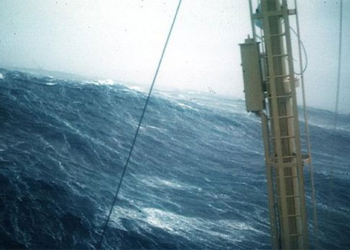

Methane clathrate retrieved by a German research vessel from the ocean – (Photo: Wusel007).

On our planet, solid sediments known as methane clathrate form when marine organisms convert organic materials—such as the remains of living organisms—into methane gas trapped in a “cage.”

This reservoir gradually fills with methane gas. Many types of microorganisms begin to consume them, while the remaining gas escapes into the ocean and mingles with the atmosphere.

It is these methane-eating organisms that have enabled the strange white structure to exist despite the extreme pressure of the ocean floor, thus revealing details about the mysterious deep-sea bacteria.

The research results indicate that a type of protein known as “clathrate-binding protein from bacteria” (CbpAS) influences the growth of methane clathrate by interacting with its structure.

Notably, according to previous NASA studies, it is believed that methane clathrate also exists on many extraterrestrial worlds, such as Titan and Enceladus of Saturn or Europa of Jupiter.

According to Space, findings from the new research suggest that if bacteria exist on other worlds, they may have done the same to create methane clathrate and influence the composition of the oceans and atmospheres of those worlds.

Therefore, the authors conclude that to find extraterrestrial life, we may need to follow the traces of methane.