The Garamantes Empire once thrived by utilizing technology to extract groundwater in the Sahara Desert but ultimately faced demise when water sources ran dry.

With low rainfall and high temperatures, the Sahara Desert is one of the most extreme and inhospitable environments on Earth. Although the Sahara was much greener in cycles throughout its history, an ancient society living in a climate similar to today managed to find ways to collect water in the arid desert until the water sources were depleted, according to Phys.org.

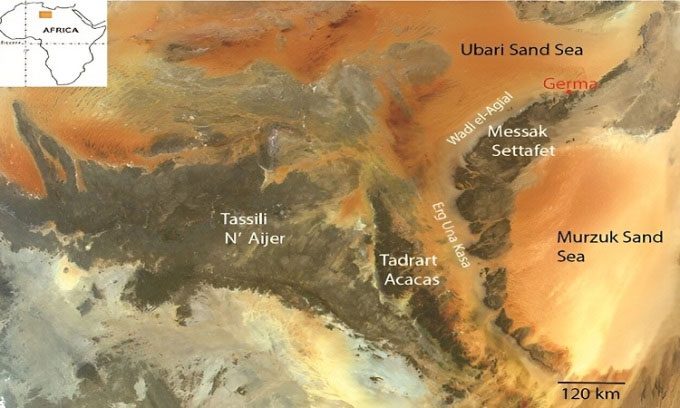

Area where the ancient Garamantes lived. (Photo: NASA/Luca Pietranera)

A new study set to be presented at the GSA Connects 2023 conference on October 16 by the American Geophysical Union outlines a series of favorable factors that allowed the ancient civilization in the Sahara, the Garamantes Empire, to exploit groundwater beneath the surface, sustaining their society for nearly a millennium before the water ran out.

According to Frank Schwartz, a professor at the School of Earth Sciences at Ohio University and the lead researcher, monsoon rains transformed the Sahara into a relatively fertile environment 5,000 to 11,000 years ago, providing surface water resources and suitable conditions for civilizations to develop. When the monsoon rains ceased 5,000 years ago, the Sahara became a desert, and many civilizations withdrew from the region.

The Garamantes lived in the southwestern desert of Libya from 400 BC to 400 AD under conditions of extreme aridity similar to today and were the first urbanized society to form in a desert without a continuous flowing river. The lakes and rivers that existed during the lush Sahara had long disappeared by the time the Garamantes arrived, but significant amounts of water remained stored in the sandstone aquifer, potentially one of the largest aquifers in the world, according to Schwartz.

Trade routes using camels from Persia across the Sahara provided the Garamantes with technology to collect groundwater, utilizing underground water conduits or aqueducts. This method involved digging gently sloping tunnels on the hillside just below the water table. Groundwater would then flow into the tunnels, leading to an irrigation system. The Garamantes dug a total of 750 kilometers of underground tunnels and vertical shafts to collect groundwater, with construction activity peaking between 100 BC and 100 AD.

Schwartz combines archaeological studies with hydrological analysis to understand how terrain features, geology, and rainfall patterns created ideal conditions for the Garamantes to exploit groundwater. According to him and his colleagues, the Garamantes were fortunate to have favorable environmental conditions, including prior humid weather, suitable terrain, and unique groundwater conditions that allowed their water conduit technology to function. However, their luck ended when the water table fell below the level of the tunnels, leading to the empire’s demise.