According to the latest research, the development of Neanderthals was faster than the maturation process in modern humans.

This means that Neanderthal children could physically mature at an earlier age compared to modern humans, thereby improving their chances of survival in the challenging environmental conditions of the Pleistocene era.

These conclusions come from a study of the milk teeth of Neanderthals recovered from a fossil site in Croatia. Scientists determined that these teeth had developed sufficiently to emerge from the jawbone several months earlier than those of an average child. The faster development of Neanderthals would allow Neanderthal boys and girls to start eating solid food earlier, facilitating their physical development at a quicker pace.

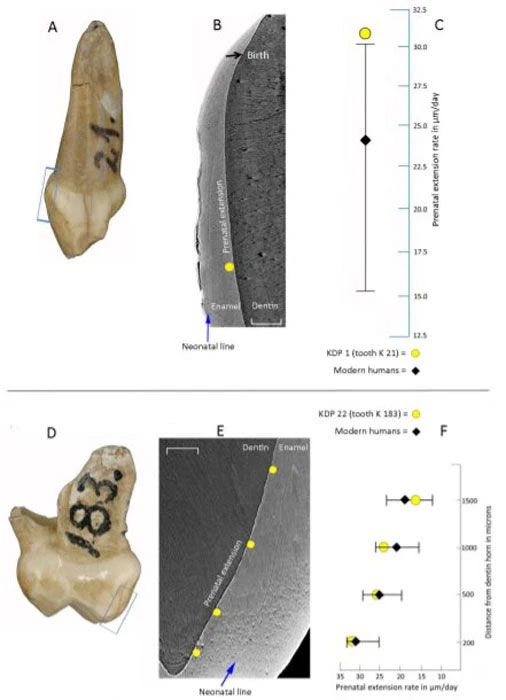

Neanderthal child’s milk tooth.

A recent study, based on five milk teeth found at the Krapina site in Croatia, shows that the development of Neanderthal children is faster than the maturation process in modern humans.

As detailed in a paper published by the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, a group of international scientists conducted an extensive analysis of five milk teeth recovered from the Krapina Neanderthal archaeological site in Croatia, dating back to the Pleistocene era. This collapsed cave contains the fossilized remains of 80 deceased Neanderthals, making it the most “populated” Neanderthal site found anywhere in the world.

Through dating methods, archaeologists determined that the five milk teeth belonged to three Neanderthal infants who lived between 120,000 and 130,000 years ago. They are intact and exceptionally well-preserved, providing an ideal foundation for this groundbreaking research.

“The relative growth rate of human and Neanderthal teeth is a hot topic. Some say Neanderthals developed faster, while others argue they fall within the range of human variation,” said co-author Helen Liversidge in a report on the new discovery from the Natural History Museum in London. Professor Liversidge is a dental anthropologist at Queen Mary University and a scientific associate of the museum.

She explained: “This is the first time we have Neanderthal children’s teeth, allowing us to analyze and determine the development of the roots to see whether they would erupt earlier or later compared to modern humans. We found that Neanderthal children’s teeth seem to erupt faster, and their milk teeth come in earlier than those of humans today.”

Liversidge and her colleagues took high-energy X-rays of the five milk teeth to reveal more details about their structure and development patterns. They tracked the growth rate by measuring the enamel layers, which stack on the tooth body as it grows. There is a specific marker on the newly erupting milk tooth indicating how much it has grown before birth and how long after that, allowing for accurate calculations of the tooth’s growth rate.

After analyzing the X-ray images, researchers discovered that the incisors of Neanderthal children grow much faster than those of typical human infants. The molars of these infants (the back teeth) also develop faster, preparing them to chew more robustly at an earlier age.

It appears that Neanderthal children experience tooth development earlier than human children by three to five months. This means their first teeth would emerge from the jaw and be visible around four months of age, with the last teeth erupting by seven months.

Neanderthal children appear to develop teeth earlier than human children by 3-5 months.

The faster dental development of Neanderthal children suggests that weaning would occur earlier and a more diverse and rich diet would come sooner. Neanderthal children would have a diet similar to that of adult Neanderthals, including red meat, seafood, mushrooms, and various plant foods. This would support physical growth and cognitive development, allowing Neanderthal children to become sturdier and more adaptable than their Homo sapiens peers of the same age.

This rapid development in Neanderthals may be related to their relatively short lifespan. Previous studies have revealed that 85% of Neanderthals died before the age of 40. It is unclear whether this was due to harsh environmental conditions, vulnerability to disease, or genetic factors that caused the species to age rapidly. It could be a combination of such factors.

Regardless of the reasons for their reduced lifespan, Neanderthals would have needed to reproduce abundantly to maintain a sustainable population size. Faster childhood development means quicker growth into adolescence and adulthood, making it easier for Neanderthals to sustain higher birth rates.

Neanderthals had short lifespans.

The discovery of early dental development in Neanderthals is significant. However, the question of their physical characteristics and the evolution of the species remains.

Helen Liversidge pointed out: “It is difficult to say whether the Krapina samples represent the entire species because we only have a few teeth. We will need more fossil samples to create a clearer picture.”

The limited number of samples raises the possibility that Neanderthals living in different regions of Eurasia may have developed differently.