Hurricane Ian left a devastating path across much of southern Florida, USA. This was clearly reflected in ground reports, but it also showed up in satellite data. Using a new method, a team of environmental and space analysts led by Zhe Zhu and Su Ye at the University of Connecticut was able to quickly provide a rare panoramic view of the damage across the state.

Climate change once seemed like a distant threat. But now it is not. Humanity has clearly seen the “faces” of climate change. We see it in hurricanes, floods, heatwaves, wildfires, and droughts. Hurricane Ian is the latest example. Satellite images and artificial intelligence reveal the extensive damage caused by Hurricane Ian. The dark areas are likely to have sustained significant damage.

By using pre-storm satellite imagery and real-time images from four satellite sensors, along with artificial intelligence, they developed a disaster monitoring system capable of mapping damage at a resolution of 30 meters and continuously updating data.

Satellites have been used to identify areas at high risk for flooding, wildfires, landslides, and other disasters, as well as to accurately assess damage after these disasters. However, most satellite-based disaster management methods rely on visually assessing the latest images, one neighborhood at a time.

The new AI system utilizes data from NASA’s Landsat 8 and Landsat 9, as shown in this rendering, along with satellites from the European Space Agency (ESA). At first glance, Hurricane Ian may appear to be an isolated event. But it is not – it is part of a weather pattern that includes hurricanes and stronger superstorms as the oceans continue to record record warmth, according to The Guardian.

The new technique introduced will automatically compare pre-storm images with current satellite images to quickly detect anomalies across vast areas. These anomalies could be sand or water where there shouldn’t be sand or water, or heavily damaged roofs that do not match their appearance before the storm. Each area with significant anomalies is flagged in yellow.

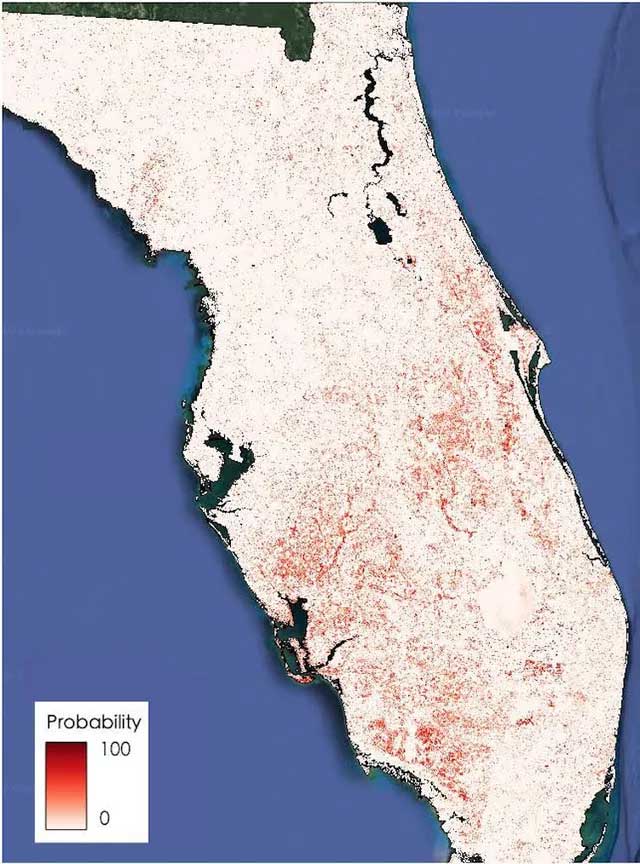

Five days after Hurricane Ian struck Florida, a map displayed yellow warning polygons across southern Florida. The research team found that it could detect damage patches with an accuracy of about 84%.

A natural disaster like a hurricane or tornado often leaves significant spectral changes on the surface, meaning changes in how light reflects off anything there, such as homes, land, or water. The new algorithm will compare reflectance patterns based on pre-storm imagery with post-storm reflectance.

The system detects changes in the physical characteristics of natural areas, such as changes in moisture or brightness and the overall intensity of the change. An increase in brightness is often associated with exposed sand or bare land due to storm impacts.

<pUsing machine learning models, the research team can use these images to predict the likelihood of disturbances, measuring the impact of natural disasters on the land surface. This approach allows scientists to automate disaster mapping and provide comprehensive coverage of the state immediately after satellite data is released.

The system uses data from four satellites including Landsat 8, Landsat 9, both operated by NASA and the United States Geological Survey, and Sentinel 2A and Sentinel 2B, launched as part of the European Commission’s Copernicus program.

If humanity continues to warm the planet, causing the ice sheets in Greenland and West Antarctica to melt rapidly, we will have to measure rising sea levels in yards rather than just feet. It is crucial to enhance resilience and adapt to the inevitable changes. Current monitoring technologies do not necessarily provide a comprehensive view of storm damage, but AI can change that.

Extreme storms accompanied by devastating floods have been recorded with increasing frequency across large areas globally in recent years.

While disaster response teams may rely on aerial surveillance and drone equipment to assess damage in small areas, it is challenging to see the big picture of a widespread disaster like hurricanes and other tropical storms. The new system proposed by the research team will provide a rapid approach using government-produced free imagery to view the larger overall picture.

A current drawback is that the timing of these images is often not widely published until several days after the disaster.

Currently, scientists at the University of Connecticut are working to develop a near real-time monitoring system for the entire United States to quickly provide the most up-to-date land information for the next natural disaster.