The recent discovery of an ancient waterway offers promising clues to unravel the long-debated mystery surrounding the construction of the Egyptian pyramids.

The construction methods of ancient pyramids have always been a mystery to modern researchers. Some theories suggest that the Egyptians utilized ramps, levers, pulleys, or even water channels to move the massive stone blocks.

However, until now, there has been no convincing evidence to support these theories, and we can only rely on the accounts of ancient historians like Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus, who visited Egypt centuries after the pyramids were built. Their narratives may not be accurate or reliable as they were based on hearsay and legends.

Now, a new study shows that an ancient branch of the Nile River could be the key to the construction of the Giza pyramids.

Historically, the Great Pyramid is attributed to Khufu based on the writings of classical authors, particularly Herodotus and Diodorus Siculus. However, during the Middle Ages, other figures such as Joseph, Nimrod, or King Saurid were also noted as the builders of the pyramid. According to National Geographic, each stone in the millions that comprise the Great Pyramid weighs at least 2.5 to 15 tons. It is the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, yet the only one that remains relatively intact, holding the record as the tallest man-made structure for nearly 4,000 years.

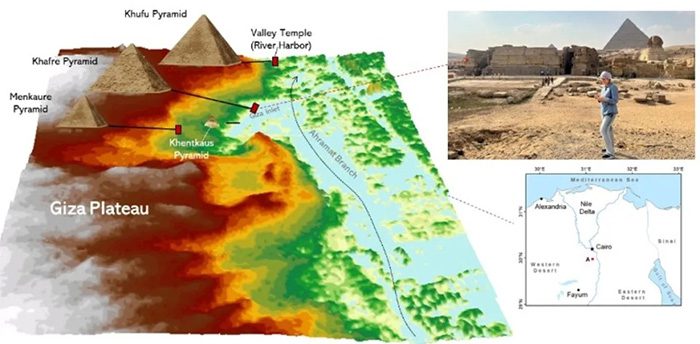

Researchers have utilized satellite radar data to reveal the hidden path of a dried-up waterway that once flowed near the pyramid sites, providing a feasible means for transporting the enormous stone blocks and the workers needed for the grand construction projects.

The study, led by Dr. Eman Ghoneim, was presented at the 13th Congress of Egyptologists. Ghoneim and her team analyzed images from space that showed the sub-surface features of the Nile Valley, discovering a buried riverbed extending approximately 100 kilometers (62 miles) from Faiyum to Giza.

The waterway, dubbed the Ahramat Branch (meaning “Pyramid Branch” in Arabic), passes through 38 different pyramid sites, indicating a close connection between the river and the monuments.

Before confirming the existence of the dried-up Nile branch, scientists already speculated on this method of water transport. An ancient papyrus discovered in 2013 revealed a port on the Red Sea where stones were loaded onto ships for transport. To locate this Nile branch, the scientific team dug holes in the desert around the pyramids in search of ancient pollen from plants like papyrus and bulrush, which thrived in wet environments. The study indicates that during the reign of Pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure, about 4,500 years ago, a stable branch of the Nile extended toward the pyramids. This river branch has long since disappeared. Pollen from drought-resistant plants like grass shows that this river branch had been dry for centuries by the time King Tutankhamun ascended to the throne around 1350 BC, according to The Times.

Ghoneim told IFLScience that the Ahramat Branch was not a minor tributary but a major branch of the Nile, with a width comparable to the current river. She estimates it was several hundred meters wide in some areas and may have been active during the Old and Middle Kingdom periods (3,700 to 4,700 years ago), when most of the pyramids were constructed.

The presence of a significant waterway near the pyramid sites may explain how the ancient Egyptians were able to transport the massive stones and limestone used in building the pyramids.

Ghoneim suggests that most pyramids had an elevated causeway that ended with a temple in the valley, similar to a port. She added that most of these valley temples are precisely located on the bank of the branch they discovered.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is a magnificent structure standing at 139m, with near-perfect geometric structure, adorned with intricate details, located on the outskirts of Cairo and a testament to the unparalleled power and wealth of the Pharaohs during the golden age of ancient Egypt. The Great Pyramid has been dated to approximately 4,600 years old using two main approaches: indirectly, through records of Khufu and its dating based on archaeological and textual evidence; and directly, through radiocarbon dating of organic materials found within the pyramid and its mortar.

Researchers plan to conduct further investigations to confirm the dating and function of the Ahramat Branch, as well as its impact on ancient Egyptian civilization. Ghoneim noted that this discovery could also help locate other lost cities and towns that were abandoned as the Nile River shifted over time.