The Ginkgo tree, the nautilus (a type of mollusk), and the coelacanth are not biologically related, but their evolutionary history shares an astonishing similarity: these creatures are referred to as “living fossils.” In other words, they seem to have escaped the changes that typically occur over time through the process of evolution.

For the past 85 years, the coelacanth has been dubbed a “living fossil” because it evokes the era of dinosaurs. These fish belong to the group known as lobe-finned fish, which also includes lungfish (fish with lungs) and four-legged animals.

Few vertebrates evoke as much curiosity as the coelacanth, both due to the fascinating story of its discovery and its status as a “living fossil.” Moreover, only two species of coelacanth have survived this long evolutionary process, and they are currently threatened with extinction.

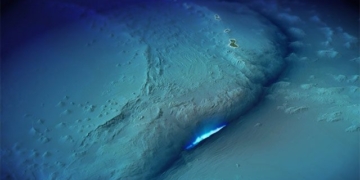

Ngamugawi wirngarri coelacanth in its Devonian coral reef habitat. (Photo: Katrina Kenny)

A Major Discovery in Western Australia

Employing the latest technological advances and innovative analytical methods, scientists are striving to gain a deeper understanding of the evolutionary processes of these fascinating species, often referred to as “living fossils”, and the 410-million-year evolutionary history of the coelacanth.

This study, recently published in the journal Nature Communications, identified and described the fossil of an extinct coelacanth species that is 380 million years old, discovered in Western Australia.

These fossils are remarkably well-preserved and date back to a critical transitional period in the long evolutionary history of these fish. This research is the result of international collaboration among scientists affiliated with organizations in Canada, Australia, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Thailand.

Charles Darwin was the first to use the phrase “living fossil” in his book On the Origin of Species in 1859, referring to living species he considered “anomalous” compared to others at that time. Although this concept was not clearly defined during Darwin’s era, it has since been adopted by hundreds of biologists. However, the term “living fossil” remains a topic of debate within the scientific community.

More than 175 species of coelacanths lived between the Late Devonian (419 to 411 million years ago) and the end of the Cretaceous period (66 million years ago). In 1844, Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz identified a specific group of fossil fish, which he named the coelacanth group.

For nearly a century, it was believed that coelacanths had gone extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, around 66 million years ago. During this time, nearly 75 percent of life on Earth became extinct, including most dinosaurs.

Then, on December 22, 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, the curator of the East London Museum in South Africa, received a call from a fisherman who had caught a rare and strange fish. She recognized it as an unknown species and contacted South African ichthyologist (fish biologist) JLB Smith, who confirmed that this was indeed the first living coelacanth ever observed.

In 1939, Smith named this species Latimeria chalumnae, also known as gombessa. Since then, this species, found along the eastern coast of Africa near the Comoros Islands, in the Mozambique Channel, and off the coast of South Africa, has attracted significant scientific interest.

In 1998, a second living coelacanth species, Latimeria menadoensis (known as ikan raja laut, or king of the sea, in Indonesian), was discovered off the coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia. These two species are the only surviving representatives of an ancient lineage that appears to have evolved very little over the past few million years.

After the discovery of Latimeria chalumnae, coelacanths were regarded as vertebrates whose body shape changed little over time, indicating a slow evolutionary process.

To date, over 50 species of fossil coelacanths have been identified at Gogo. This diverse group of fish, along with various marine invertebrates, coexisted in warm Devonian coral reefs approximately 380 million years ago.

The latest research suggests that coelacanths evolved rapidly at the beginning of their history during the Devonian period, but this evolutionary process slowed considerably afterward. Evolutionary innovations nearly ceased after the Cretaceous period, indicating that for some traits, coelacanths like Latimeria seem to have been “frozen” in time. The slow evolution of coelacanths suggests that they are not “living fossils” but rather the result of a complex evolutionary process.