A new study based on the remains of 70 individuals belonging to a colossal species of beast, weighing 13 tons, has shed light on a period 125,000 years ago, hinting at the presence of a human hunter.

According to Sci-News, the research led by Professor Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser from Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz and the MONREPOS Archaeological Research Institute (Germany) analyzed the most extensive collection of “straight-tusked elephants” known to date.

This collection consists of 70 well-preserved skeletons from the site named Neumark-Nord 1, located approximately 10 km south of Halle in central Germany, excavated between 1985 and 1996.

Model of the extinct straight-tusked elephant alongside a female scientist – (Photo: Lutz Kindler, LEIZA).

Straight-tusked elephant (scientific name Palaeoloxodon antiquus) is an extinct species of elephant, significantly larger than modern elephants, with some individuals weighing up to 13 tons, much larger than modern Asian elephants, which weigh around 3-4 tons, and African elephants, which weigh about 6 tons.

The remains indicate that the large male individuals greatly outnumbered the females.

Modern techniques have allowed scientists to reconstruct the historical phase that occurred through the data preserved in 3,122 fragments of bones from the aforementioned 70 skeletons, along with information from the site where they rested.

All evidence shows a “shadow” of humanity, but not our Homo sapiens ancestors, rather an ancient human species that also became extinct like the beasts at the site: Neanderthals.

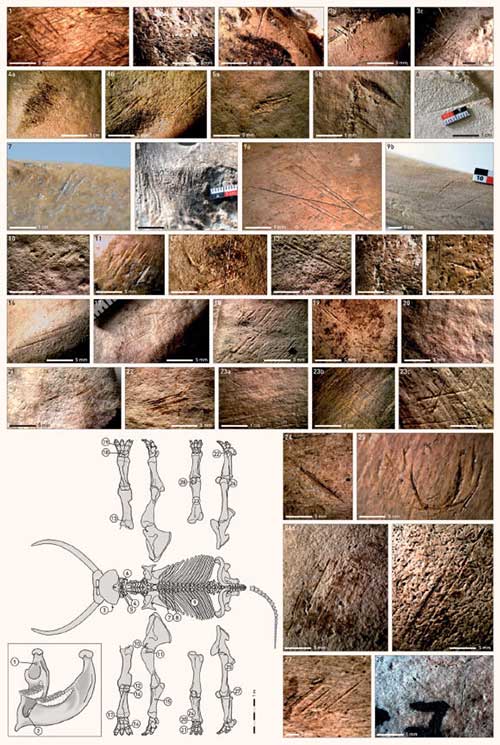

Artifacts found at the ancient beast cemetery belonging to the straight-tusked elephant and bearing the “shadow” of humanity – Photo: SCIENCE ADVANCES

The most surprising finding is the clear evidence of human interaction at this “monster graveyard”, not only through marks on the bones but also through the mentioned sexual dimorphism.

Scientists predict that this extinct beast likely exhibited behaviors similar to modern elephants, with males wandering alone, making them targets for Neanderthals. This “monster graveyard” was not a site where elephants came to die, as modern narratives might suggest, but rather a place where Neanderthals processed the animals they hunted.

This provides surprising insight into the social capabilities of Neanderthals, an extinct relative of ours once thought to be less developed. The authors explain that hunting these large animals required close cooperation among group members, similar to the processing of prey, which involved multiple steps.

An average straight-tusked elephant, weighing about 10 tons, could provide approximately 2,500 meals for Neanderthals, and in a society 125,000 years ago, this “giant restaurant” indirectly indicates a large, well-organized community. It may be much larger than the previously suggested small groups of 25 people indicated by past archaeological studies.

This also serves as further evidence affirming that Neanderthals were skilled hunters. Previous studies have suggested they may have hunted mammoths and other ancient gigantic animals.

The study was recently published in the scientific journal Science Advances.