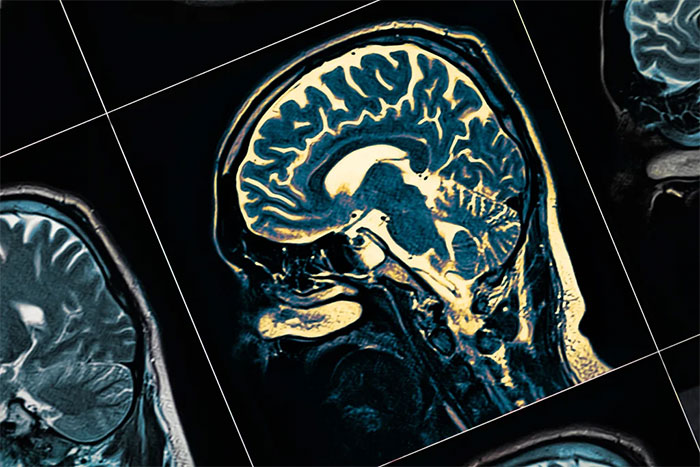

According to the New York Times, a new study published in the journal Nature on March 7 reveals significant findings. This is the first research to utilize brain scan data (MRI) from individuals infected with Covid-19 before they contracted the virus and several months afterward. Consequently, neurologists not involved in the study highly value this discovery.

However, they caution that the impact of these changes is not entirely clear, and not all individuals with Covid-19 (F0) may experience long-term damage or profound effects on their thinking and memory.

Mild Cases of Covid-19 Also Affected

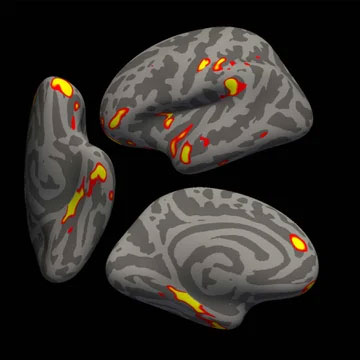

The study was conducted on 785 individuals aged 51-81, revealing shrinkage and tissue damage primarily in brain regions associated with olfaction. The research team from the University of Oxford in the UK noted that some of the affected areas also participate in other brain functions.

The volunteers were part of the UK Biobank project, a repository of health data from approximately half a million people in the UK. Each participant underwent two brain scans, spaced about three years apart, and completed several basic cognitive tests. Between the two scans, 401 individuals tested positive for nCoV, all of whom contracted the disease between March 2020 and April 2021. The second scan occurred approximately 4-5 months after they were infected with the virus.

The red and yellow areas indicate the most significant brain shrinkage among the 401 individuals with Covid-19. (Source: Professor Gwenaëlle Douaud, University of Oxford and the National Institutes of Health, USA).

The remaining 384 individuals served as a control group because they had never contracted Covid-19, sharing similar characteristics in terms of age, gender, medical history, and socioeconomic status with those infected.

With normal aging, individuals lose a small amount of gray matter each year. Previous studies indicated that in areas related to memory, humans lose about 0.2-0.3% of gray matter annually.

However, Covid-19 patients in this study experienced greater losses. Approximately 0.2-2% of gray matter in different brain regions disappeared over three years. A 2% reduction corresponds to about ten years of aging in healthy individuals. They also experienced a more significant loss of overall brain volume, with tissue damage in specific areas.

After 4.5 months of having Covid-19, the thickness of gray matter in the olfactory-related brain regions decreased significantly. This area is also known as the anterior cortex and parahippocampal gyrus. This finding is thought to help explain the olfactory decline that many Covid-19 patients experience.

Notably, it is striking that most affected patients were those with mild cases of Covid-19 who did not require hospitalization. Most participants recovered from Covid-19 at home, suggesting that the findings may apply to the majority of recovered patients worldwide.

The lead author of the study, Professor Gwenaëlle Douaud from the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at the University of Oxford, noted that the number of hospitalized patients in this project was just 15, which is too small to draw conclusions. However, the results still indicate that they experienced more severe brain shrinkage compared to the mild cases.

Dr. Serena Spudich, head of the Department of Neurological Infections and Global Neurology at Yale School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study, expressed surprise at the amount of gray matter lost in these individuals.

“This is fairly compelling evidence that something is changing in the brains of those with Covid-19. However, drawing clinical conclusions about mild cases is quite challenging. We do not want the public to fear that contracting Covid-19 will inevitably lead to brain damage and impaired functioning,” the expert stated.

The new study found that individuals with Covid-19 may experience brain shrinkage and gray matter loss after infection. (Image: WBTW).

Concerns

The second finding noted by the research team is that individuals infected with Covid-19 exhibited greater cognitive decline in tests related to attention, work efficiency, and the execution of complex tasks.

Nonetheless, other experts argue that this testing remains quite rudimentary, which becomes a limitation of the report. They agree that it is very challenging to assess whether gray matter and tissue damage in Covid-19 patients affect their skills and cognitive abilities.

Associate Professor Benedict Michael from the University of Liverpool, UK, remarked: “None of them were tested for cognitive function in sufficient detail to determine if there are significant deficits. We do not know how this affects the quality of life or functionality of the patients. In general, it is very difficult to draw conclusions.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Douaud mentioned that although some of the largest gray matter losses occurred in regions related to olfaction, memory, and other functions, the individuals did not perform poorly on the tests. They took longer to complete tasks connecting related letters and numbers. This may indicate weaknesses in focus, processing speed, and other skills.

According to Dr. Douaud, this decline correlates with gray matter loss in a specific region of the cerebellum. However, the authors could not establish a cause-and-effect relationship.

Another significant limitation of the study is the lack of information about symptoms in individuals with Covid-19, including whether they experienced loss of smell. The authors could not determine which individuals suffered from sequelae, so it remains unclear if these findings are related to Long Covid.

The differences between infected and non-infected individuals increased with age. For instance, in a trail-finding test, performance was similar in both groups aged 50-60. However, the performance gap was significantly larger in the older age group.

“I do not know if this is because younger individuals recover faster or if they are not affected as much from the outset,” Dr. Douaud said.

The findings are thought to help explain the causes of post-Covid-19 loss of smell in some individuals. However, this perspective has received mixed opinions. (Image: Freepik).

This also prompted Dr. Michael to warn that the findings cannot be used to explain why younger individuals experience brain fog and other cognitive issues after Covid-19. Since gray matter and tissue damage were only measured at one point after infection, it is unknown whether this was merely a transient change that later recovered or something else.

The causes of these changes in the brain remain unclear. The authors mentioned hypotheses such as inflammation and the phenomenon of sensory loss due to disrupted olfaction.

Additionally, Dr. Avindra Nath, head of the Department of Neurological Infections at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in the USA, who was not involved in the study, noted that we need to consider another important question: whether these changes in the brain could make individuals with Covid-19 more susceptible to dementia.

Meanwhile, other studies have not found similar changes in the brains of individuals with pneumonia not caused by nCoV. Dr. Nath recommended further examination of individuals infected with other strains of the coronavirus or influenza to provide additional evidence for final conclusions.

Experts assert that the greatest value of the study lies in demonstrating that something has occurred within the brains of individuals with Covid-19. However, it remains quite vague and challenging to measure. The current task is to examine the cognition, psychiatric symptoms, and behaviors of individuals with Covid-19 to understand what this discovery means for patients.