-

Construction Period: 1950-1954

-

Location: Ronchamp, Vosges, France

|

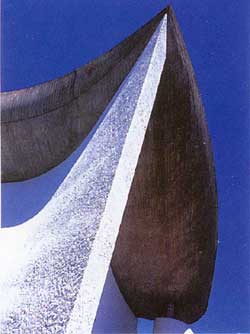

| The flat, dull gray roof threatens the many white walls that seem to celebrate the masterful interplay of light and structure devised by Le Corbusier. |

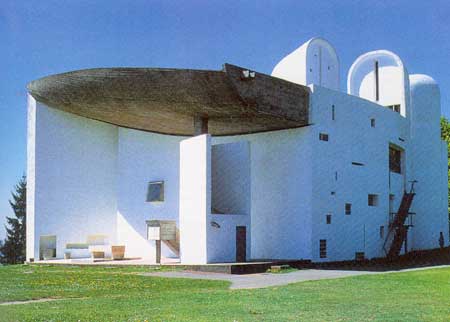

For those who have visited Le Corbusier’s Notre Dame du Haut chapel in Ronchamp, no combination of content and imagery can compare to the intense emotion experienced in spirit, as if there is a magic emanating from the structure. This humble yet extraordinary chapel synthesizes many influences present in Le Corbusier’s post-World War II architecture, demonstrating a sensitivity to the building’s site that is less apparent in most of his other urban projects. The chapel is equally significant as a remarkable testament to Father Alain Couturier’s efforts to persuade fellow clergy to revitalize church art by commissioning the most talented modern architects and artists.

Father Couturier commissioned Henri Matisse to decorate the Dominican chapel in Saint Paul de Vence, but he recognized Le Corbusier’s talent and suggested to the Diocese of Belfort that they engage this architect to replace the Notre Dame du Haut chapel, which had been destroyed during World War II. Although he proclaimed himself an atheist, Le Corbusier was deeply sensitive to the spaces created in many religious structures he had visited, and thus accepted the commission. Later, Father Couturier also asked Le Corbusier to design the much larger La Tourette monastery near Lyon.

Environment

Situated on a prominent hill, not far from Le Corbusier’s ancestral Jura village, the site has been a place of worship since the time of the Sun God, followed by the Romans, and later, during the Middle Ages, a pilgrimage church was established to honor the Virgin Mary. Le Corbusier immediately identified the location and gradually accepted the overall form that his assistant, André Maisonnier, distilled and detailed.

A small team of workers under Maisonnier’s direction constructed the chapel largely by hand, with frequent personal supervision from Le Corbusier. The spontaneous nature of the construction closely reflects the creation of a sculpture rather than a predetermined architectural project.

Le Corbusier’s initial sketch shows the final shape of the chapel.

From a distance, the structure appears to rise majestically from the hilltop. As one approaches from the village below, the sculptural form of the chapel gradually reveals itself, astonishing visitors who never lose the feeling of exploration and wonder. The reasons behind this dramatic yet harmonious sensation are undoubtedly complex, but perhaps stem from the architect’s dedication to designing each final detail.

The harmony associated with the overall proportions, the patterns on the floor, the size of the windows, and the spaces—every dimension—originates from the Modulor measurement system based on human scale and the application of the Golden Section developed by Le Corbusier himself. The sense of discovery is maintained through the delicate development of concave and convex shapes, rough and smooth textures.

Structure

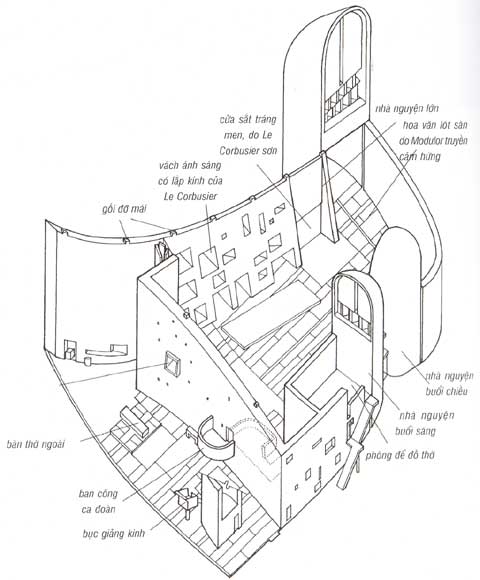

Three curved walls serve dual purposes: they form external and internal spaces that embody a sculptural masterpiece while providing structural stability for the entire chapel, allowing the roof and three spires to largely support themselves. Each of the three walls is constructed from concrete panels and infill (using stone salvaged from the previous chapel) which are then coated with metal mesh and sprayed concrete. Each wall has a unique structure, enhancing the illumination of the chapel throughout the day.

The chapel’s stripped diagram. Constructed on the site of the previous chapel.

The massive concrete roof, often thought to be inspired by the shape of a horseshoe, which the architect admired, is in reality a lightweight concrete shell, reminiscent of an airplane wing in cross-section. This analogy seems fitting as the roof is, in fact, “a boat” drifting toward the eastern and southern facades. The small supports, invisible from the outside as they are hidden in shadow, and not easily discernible from the inside due to the brilliant light where the roof and walls intersect, create the impression of a monumental roof threatening the independent walls. Le Corbusier also employed this detail in La Tourette.

|

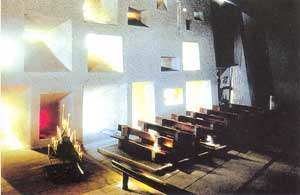

| The voids in the light wall and all the interior woodwork adhere to the architect’s Modulor sizing system. The stained glass was also installed by Le Corbusier. |

The eastern façade features an open altar, a pulpit, and a choir space hidden within the cantilevered roof to serve the crowds of pilgrim worshippers, with a terraced layout giving the eastern lawn a circular profile. A statue of the Virgin Mary from the former chapel is placed in a wall niche visible from both inside and outside.

Facing south is the distinctive light wall—a massive stone wall varying in thickness from 1.5 to 4.5 meters, curved in plan and tapering in cross-section. Embedded in the plastered stone wall are voids determined by the Modulor, with stained glass installed by Le Corbusier, and a large south entrance designed by him for the communion, featuring heat-resistant enamelled iron.

Actual Measurements:

-

Main chapel:

– Length: 25m

– Width: 13m

– Maximum height at the altar wall: 10m -

Half-dome height: 15 and 22m

-

Materials: reinforced concrete, infill stone, sprayed concrete

Light Harmony

Visitors soon discover that the chapel also functions as a giant sundial, with a rich array of structures, angles, shapes, and wall niches precisely marking the passage of time. The transition of sunlight through the rough edges at the “bow of the boat” in the southeast to the light wall in the south seems to extend indefinitely. From dawn to dusk, the structure continually captures the attention of visitors, constantly changing its form and characteristics.

Sunlight illuminating the rich form of the chapel to mark the passage of time

The harmonious interplay of light and shadow is fascinating and continues within the interior, where an ever-changing atmosphere is created by the light tower with various angles determining the appropriate time of day for using each of the three chapels. The rough concrete roof, light-blocking surfaces, smooth stone floor, roughly carved wooden benches, stained glass windows, and heat-resistant enamelled doors all combine to create a rich palette between materials and textures.

The combined effect of the suspended roof, light walls, and the deep resonance created by the curved surfaces has made the chapel a very modern, intimate, and majestic setting, affirming the intuitive capabilities of Le Corbusier and Father Couturier.