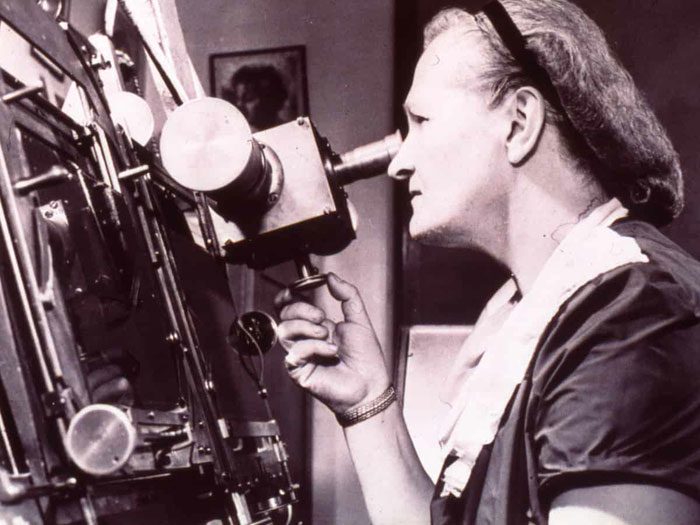

For a long time, many scientists misunderstood the composition of the Sun, until a 25-year-old graduate student wrote a doctoral thesis proving that the Sun and other stars are primarily made up of helium and hydrogen.

The graduate student who made this groundbreaking discovery was Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin. However, few know that she was responsible for this important discovery because the concept of gender equality did not exist at that time.

Regarded as the greatest female astronomer in history, her identity and contributions have been underrecognized due to gender discrimination.

Jeremy Knowles, chair of the Department of Arts and Sciences at Harvard, stated in 2002:

“The woman who discovered the composition of the universe has not been awarded any further honors since her death in 1979.

Every student knows Newton discovered the law of gravitation, Darwin discovered the theory of evolution, and Einstein developed the theory of relativity. But when it comes to the composition of the universe, textbooks simply state that the most common element in the universe is hydrogen, and no one questions how we know that in the course syllabus; that woman also had no status to advise graduate students in the astronomy department; she had no summer break, and her meager salary was merely for research “equipment,” implying that she was not recognized in the department. Yet she persevered and built her career.”

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was born in Wendor, England, in 1900. Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin was originally named Cecilia Helena Payne and changed her name after marrying Sergi Gaposchkin.

By the age of 12, Cecily had learned French and German, had a basic understanding of Latin, and was well-versed in arithmetic.

From a very young age, she dreamed of becoming a scientist and worked hard to achieve her goal.

For a long time, many scientists were mistaken about the composition of the Sun until the outstanding doctoral thesis of a 25-year-old female graduate student demonstrated that the Sun and other stars are primarily composed of helium and hydrogen.

In 1919, she was awarded a Natural Science Scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge. Although Cecilia excelled in her studies, she was not awarded a degree because the University of Cambridge did not confer degrees to women until 1948.

Cecilia realized that there were very few opportunities for women in science in England, and the only option at that time was to become a teacher. However, after being introduced to Harlow Shapley, the director of the Harvard University Observatory, she decided to pursue a career in astronomy and moved to the United States.

Her former lecturer, Arthur Eddington, wrote: “She has a broad knowledge of physical science, including astronomy, and brings invaluable energy and enthusiasm to her work. I believe she is the type of person who will dedicate her whole life to astronomy.”

From a young age, she dreamed of becoming a scientist.

In 1923, she became a National Research Fellow at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. From 1925 to 1927, Cecilia was appointed as a technical assistant to Harlow Shapley, but the salary at that time was very low and did not match Cecilia’s expertise and achievements; however, at least Cecilia could have a place to stay and continue her research.

In 1925, Cecilia published a paper related to her thesis. At that time, astronomer Otto Struve considered this thesis to be “the most remarkable of all doctoral theses in astronomy.”

Cecilia’s outstanding doctoral thesis claimed that stars are primarily composed of helium and hydrogen, but this statement was met with skepticism.

When Cecilia’s doctoral thesis was under review, astronomer Henry Norris Russell convinced her not to present her thesis but to publish it in 1930 under his name. Her 200-page research was overlooked and appropriated.

She was once prevented from publishing her discovery about the Stark effect in the spectra of the hottest stars as well as her findings on the gravitational attraction between stars. These discoveries were later also made by others and credited to different scientists.

Sadly, this was not the only time she was discouraged from publishing her findings.

The Stark effect was discovered in the spectra of the hottest stars, but both Russell and Shapley were skeptical and did not want Cecilia to publish it. Cecilia was also barred from publishing papers about her discoveries regarding the gravitational attraction between stars.

But both discoveries were published by others many years later.

Eventually, many years later, Cecilia was offered a more appropriate position for her contributions.

Cecilia was awarded the title of Astronomer in 1938; it wasn’t until 1956 that she became the first female professor at Harvard University, the first woman to achieve this. She became the first woman to hold the chair of the Department of Astronomy at Harvard University in 1956.

She retired in 1965 and became a professor emeritus at Harvard the following year. Cecilia continued to work after retirement, serving at the Smithsonian Observatory from 1967 until her death in 1979.

Despite the gender discrimination she faced, Cecilia persevered and paved the way for other women to pursue scientific careers. Today, she is recognized as the greatest female astronomer in history.

<pWhen receiving the Henry Norris Russell Award from the American Astronomical Society, Cecilia spoke about her lifelong passion for research: “The most emotionally exciting reward for a young scientist is to be the first in history to witness or discover something.”