After completing his presidential term in March 1797, George Washington returned to his home in Virginia, enjoying a peaceful rural life.

Two years later, he fell ill and passed away. In mourning for the first president of the United States, a doctor proposed a method to help him come back to life, but things did not go smoothly.

A Bold Idea That Failed

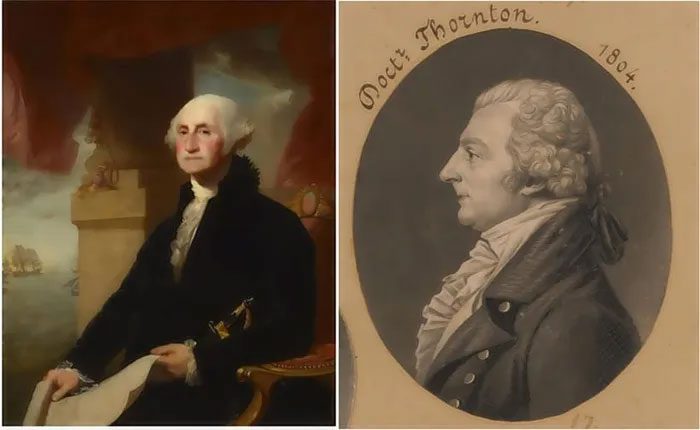

Portrait of George Washington painted two years before his death (left) and Dr. William Thornton.

On the morning of December 15, 1799, Dr. William Thornton was “racing against death” across the freezing countryside of Virginia, hoping to save a life. If his horse could reach George Washington’s doorstep before the former president succumbed to a sudden viral infection, this doctor believed he could save his dear friend.

However, upon arriving and stepping into the parlor of the Mount Vernon estate, Thornton saw people mourning over Washington’s lifeless body. The deceased’s family told Thornton he had arrived too late to prevent the former president’s death. Nevertheless, the doctor shocked those present by declaring that he could bring Washington back to life.

Born in the British West Indies in 1759, Thornton studied medicine in Scotland before moving to America and becoming a citizen in 1787. Having researched sleep science, Thornton recorded dozens of cases of animals and humans being revived from states of bodily cessation.

He joined the Royal Humane Society, an organization established in London in 1774 to promote advanced medical techniques in resuscitation—specifically, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, first described by surgeon William Tossack in 1744. This process aimed to restart breathing and heartbeat in drowning victims.

At a time when doctors sometimes confused deep comas with death, the fear of being buried alive led to the invention of safety coffins, such as those with a string that a person inside could pull to ring a bell above ground, signaling that they were still alive.

Washington feared an accidental burial as he lay in bed on the evening of December 14, 1799. His last directive to his secretary, Tobias Lear, was to wait at least two days before burying his body.

The former president endured 48 hours of agony after suffering from a severe throat infection, believed to be acute laryngeal edema, which made swallowing and breathing difficult.

As he gradually suffocated, the doctors and attendants at Mount Vernon withdrew 40% of his blood—over two liters—believing that four bloodlettings would correct the imbalance of four essential fluids—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile, thought to be the causes of the infection.

The doctors also applied cantharides to his blisters, wrapped his throat in a poultice made from wheat, administered enemas and laxatives, until Washington requested that they stop these efforts as they were only causing him more pain.

When news of the 67-year-old former president’s condition reached Washington, D.C., Thornton hastily rode to Mount Vernon, where he was a regular overnight guest.

Although he was not Washington’s personal doctor and had never practiced medicine after arriving in the United States, Thornton felt “confident that he could help him recover” by performing a creative yet extremely rare technique—tracheotomy.

But upon encountering Washington’s stiff body, Thornton recalled the cases he had read about fish coming back to life after being frozen and planned to resurrect the former president.

He proposed to “thaw” Washington’s body in cold water before warming it with blankets. Then, he would create an airway to the lungs through tracheotomy and “inflate them with air to create artificial respiration.” Thornton’s final step would be to transfuse sheep’s blood into the patient.

However, no one at Mount Vernon shared his belief. Particularly, the family respected Washington’s last wishes given to his doctors the day before: “I implore you not to trouble me any further; let me go in peace.”

Painting depicting the scene of President George Washington’s death.

The President’s Final Resting Place

Days after Washington’s death, President John Adams asked Martha Washington, the executor of her husband’s will, if she would like to move the former president’s remains to the Capitol.

Although she had planned to bury her husband permanently, the grieving widow agreed to the suggestion. However, due to a lack of funds and materials, the construction of the Capitol was delayed for decades, hindering the process of moving Washington’s remains.

As the 100th anniversary of Washington’s birth approached in 1832, public opposition in Virginia to moving their hero’s remains intensified.

By the time his remains were placed in a newly constructed tomb at Mount Vernon on October 7, 1837, the idea of the first president resting at the Capitol had completely failed. The tomb at Mount Vernon now contains the remains of Washington, his wife, and 25 other family members.

| George Washington (1732 – 1799) was the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775 – 1783), leading colonial forces to defeat the British and becoming a national hero. In 1787, Washington was elected President of the Constitutional Convention. Two years later, he became the first president of the United States, serving two terms from 1789 to 1797. |