In the history of atomic bomb development, uranium bombs and plutonium bombs can be viewed as twin siblings. Along with U-235, the Pu-239 nuclei were also used to create atomic bombs, specifically the second bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945.

The Twin Siblings

|

|

Photo of the explosion in Nagasaki on August 9, 1945, which resulted in 73,000 deaths |

The emergence of the twin siblings, the uranium bomb and the plutonium bomb, nearly coincided with a significant moment in history, shocking the world. Just three days apart, during that fateful summer of 1945 for Japan.

On the morning of August 6, the uranium bomb devastated the city of Hiroshima. By 11:02 AM on August 9, the plutonium bomb struck the city of Nagasaki. This bomb, containing the explosive Pu-239, measured approximately 3.25 meters in length, had a diameter of 1.52 meters, and weighed 4.5 tons, humorously named “Fat Man,” similar to the nickname “Little Boy” given to the uranium bomb.

The destructive power of the plutonium bomb was equivalent to 21,000 tons of conventional explosives (commonly known as TNT – Trinitrotoluene). It completely destroyed 6.7 square kilometers of property (one-third of Nagasaki’s buildings) and claimed the lives of two-thirds of the population (73,000 deaths and 75,000 injuries).

Plutonium – A World-Shaking Invention

The United States was not only the birthplace of the plutonium atomic bomb but also the country that discovered the existence of the new element, Plutonium.

|

|

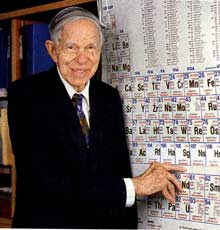

Glenn Seaborg (1912–1999) |

Glenn Seaborg (1912–1999), a legendary contemporary nuclear scientist from the United States, was the author of ten new element discoveries, including Plutonium.

The newly minted chemist Seaborg, at just 28 years old, was appointed to lead a team of young scientists to embark on a unique and challenging experiment: to find a new element heavier than Uranium, termed a superheavy or super Uranium element.

Using the most advanced accelerator of the time, they bombarded a uranium target with a beam of deuterium (d) and observed the new phenomena that occurred. Prior to this, the first super Uranium element with atomic number Z=93, named Neptunium (Np), had been discovered in 1940 by a different research team. This discovery ignited hope for the new research group.

That night, Sunday, February 23, 1941, the lights on the third floor of the Gilman Hall at the University of California (Berkeley) stayed on late into the night. The experiment had lasted ten weeks, with seemingly hopeless waiting. They continued to bombard the target with deuterium (d) for another four hours!

Suddenly, “the world seemed to shake”: an alpha particle had fallen into the counter, and a radioactive isotope of element 94 had been synthesized and identified. This was the nucleus of a new element corresponding to atomic number Z = 94: Plutonium (named after the planet Pluto), with the chemical symbol Pu.

As predicted, the first isotope of the element Pu found was Pu-238. It was produced through the process:

U-238(d,2n)Np-238 ® Pu-238 + b

In this process, the U-238 nucleus captures a d particle and becomes the Np-238 nucleus, which then emits a beta particle (β) to transform into the new nucleus Pu-238.

The emergence of the new element, Plutonium, occurred in this manner. G. Seaborg emotionally recounted the moment of Plutonium’s “birth”: When he first encountered the Pu nucleus, everything suddenly went silent, then erupted in celebration as they embraced in indescribable joy. They hurried home to succumb to the sleep they had long desired.

That was a magical night in G. Seaborg’s scientific life. For him, the element Plutonium was the most important invention of his career. With this invention, he soon shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1951 with physicist Edwin McMillan.

From Pu-235 Nucleus to Atomic Bomb

Surprisingly, the discovery of Pu had tremendous implications for humanity.

Indeed, only about a month after the discovery of Plutonium, Seaborg identified a particularly important property of one of the isotopes of Plutonium, the isotope Pu-239. Similar to the known U-235 nucleus, the new Pu-239 nucleus could also undergo fission when struck by a neutron, producing two new neutrons and releasing a significant amount of nuclear energy.

|

|

The atomic bomb nicknamed “Fat Man” was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945 |

Clearly, with this discovery, Plutonium, alongside Uranium, would become a plentiful nuclear fuel source for humanity. Unfortunately, in the tragic history of that time, before serving humanity as a valuable fuel source, Pu-239 quickly became the explosive material for atomic bombs (A-bombs).

With his groundbreaking discoveries, Seaborg was directly invited to join the newly established secret project, the Manhattan Project. He was assigned to oversee the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, working alongside Enrico Fermi to develop the atomic bomb. Here, they established a technology to extract large quantities of Pu-239 from the fission process of Uranium in the first reactor in the United States and the first in the world.

In this case, Pu-239 was generated through the process:

U-238(n,γ)U-239 —b® Np-239 —b® Pu-239

The process works as follows: the U-238 nucleus captures a slow neutron and becomes the U-239 nucleus. Almost immediately, this new nucleus emits two beta particles (β) to transform into a completely new nucleus, another isotope of the element Plutonium: Pu-239.

After three years of intense work, averaging 12 hours a day, Seaborg’s team produced enough Pu to manufacture three atomic bombs. The plutonium bomb dropped on the city of Nagasaki, Japan, was one such bomb.

Since Plutonium does not exist naturally and there are many isotopes of U-238, the method of producing Pu-239 as described is the most optimal.

Therefore, for industrial-scale Plutonium production, reactors with heavy water moderators are currently the most ideal tools compared to any other type of nuclear reactor. In this type of reactor, only natural Uranium (no enrichment needed) is used as fuel. Heavy water (D2O) serves to slow down the fast neutrons produced during reactor operation, facilitating the transformation of U-238 nuclei into Pu-239 nuclei.

At this point, readers can understand why Iran’s announcement of plans to build a heavy-water nuclear reactor has raised serious concerns and strong reactions from many related countries.

Tran Thanh Minh