-

Date of Construction: 1645 – 1695 (with many later additions)

-

Location: Lhasa, Tibet

The Potala Palace is regarded as a symbol of the Tibetan political system at the time when the country was unified under the rule of the Buddhist Dalai Lamas, performing this function admirably and creating a quintessential visual icon of Tibet for outsiders, an image that has been represented through various groups in their claims for control over Tibet. At the same time, the palace evokes the Indian origins of Tibetan Buddhism, which was actually supported by Mongolia to make its construction feasible, and adorned with Chinese architectural styles.

Photo by Hugh Richardson, representative of the British government in Tibet, taken in the 1940s.

A flag depicting Buddha flies over the building during a festival.

Named after a mystical palace in South India associated with the Tibetan protector Avalokiteshvara, the Potala Palace was built on a site believed to be the small palace of the Tibetan founder King Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century, who conceived the project for Potala. The Fifth Dalai Lama (1642-1682) is referred to as an embodiment of Avalokiteshvara. Thus, the continuity and revival of the Tibetan state after periods of division were intentionally reaffirmed.

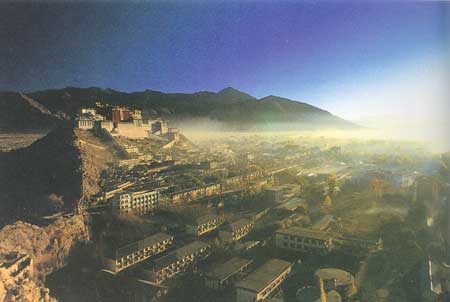

The Potala Palace stretches along the summit of a low mountain overlooking the city of Lhasa to the south, forming part of a rectangular plot of land at the foot of the mountain. The central area of the site consists of two main components: the White Palace in the east and the Red Palace in the west.

After being enthroned by Gushri Khan, the Mongolian king, as the ruler of Tibet in 1642, the Fifth Dalai Lama constructed the White Palace from 1645 to 1648 and chose it as his official residence. His last regent, Sangye Gyatso, built the Red Palace from 1690 to 1694 to consolidate the tombs of the Dalai Lamas.

Despite the recent development of Lhasa,

along with the rapid growth of modern-style buildings,

the Potala Palace still stands out in the cityscape.

Both the White and Red Palaces ultimately represent the development of ancient Indian monastery design. The rectangular assembly hall on the first floor is surrounded by rooms that overlook the interior, with two or more additional floors added above containing smaller rooms, creating an inner terraced area that is open-air, serving as a corridor above the main hall. Most of the interior spaces are chapels, monastic rooms, living quarters for the Dalai Lamas, or their burial chambers.

The tomb of the 13th Dalai Lama (approximately 1895 – 1933) led to a Western-style development until the construction of the Red Palace between 1934 and 1936. Peripheral structures such as the living quarters in the monastery at the western end and the outer defenses appear to revert to the 17th century, although many minor additions have been made over the years. Access is through a narrow gate, which can be defended after passing through several alcoves with gently sloping stairs suited for pack animals.

Despite some brief sieges, and the frequent risk of earthquakes and fires, along with damage from the Cultural Revolution, the Potala Palace has never suffered serious destruction and is generally well-maintained.

Construction Techniques

Diagram of the Potala Palace

| 1. Central Tower 2. Corner Tower 3. Southern Corner Landing 4. Structure for Thangkas 5. Nunnery 6. Western Round Tower 7. Tomb of the 13th Dalai Lama. 8. Outer Courtyard of the Red Palace 9. Hall of the Red Palace 10. Red Palace 11. Chapel 12. Fortress on the Northern Path 13. Structure on the Northern Pillar |

14. Tomb of the 5th Dalai Lama 15. Tomb of the 7th Dalai Lama 16. Tomb of the 8th Dalai Lama 17. Tomb of the 9th Dalai Lama 18. White Palace 19. Outer Courtyard of the White Palace 20. Training School for Religious Officials 21. Southern Fortress 22. Steep Path to the Southern Entrance 23. Steep Path to the Western Entrance 24. Western Fortress 25. Round Tower. |

The hilltop appears flattened into a terraced plain by cutting and filling, a traditional Tibetan technique, with the outer walls of the structure sloping down beneath the plain at various elevations, creating the impression that the mountain is rising. In terms of technology and material usage, the Potala Palace is generally not much different from rural Tibetan houses – not surprisingly, the vast workforce could only be recruited from local farmers.

The structural technique involves one of the massive load-bearing walls made of masonry – in the case of rough-hewn stones plastered with mud – to support robust wooden roof beams, which in turn support wooden floor beams that rest on the walls. Inside, the beams are supported by wooden columns through long supports. Thus, the masonry on the outside gives way to a significant amount of timber inside. A minor difference from rural housing structure is found in the small defensive towers at the eastern and western ends, which have curved walls instead of straight ones. Most of the stone was transported from sites upstream in northeastern Lhasa by porters and bamboo rafts, while the mud was largely excavated right below the site, leaving many pits later converted into decorative ponds.

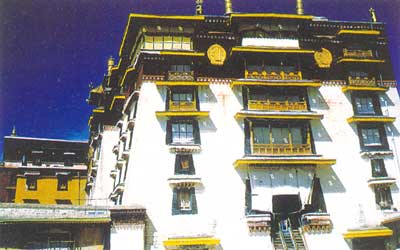

The facade of the White Palace exemplifies Tibetan religious architecture, with walls sloping inward,

vibrant color contrasts, and decorative elements concentrated toward the peak.

Both the inner and outer wall shells are built with layers of horizontally laid stones, typically about 25cm deep and 30-50cm long, separated by thin layers of smaller, slightly flatter stones packed with mud to form a flat underlay for building subsequent stone layers. In the lower wall sections and auxiliary defensive structures, the main wall stones are very irregular, and the infill layers occupy a larger proportion of the overall layers. Where the main stone layers are completely surrounded by infill stone layers, this technique is referred to as the “base layering.”

Typical of Tibetan architecture is the inward slope or 6-9 degree angle of the outer walls from the vertical, which is often slightly greater in the coarser lower cross-section. This inevitably necessitates careful angling of the infill layers toward the corners. Between the inner and outer shells, walls up to 5m thick are packed with earth, stone, and intertwined willow branches. The use of molten copper at the foundations may only be a convention in literature.

Chinese-style metal roofing supports Indian-style roof finials.

The eaves structure shades the entrances and windows, and the wall section is decorated.

The inward-leaning walls are visually counterbalanced by the wooden window frames, resembling a split at the lowest level and occasionally extending out to the balconies on the upper floors. Their lintels are sealed with the protruding floor beams and a mud roof. The flat roof connects with the retaining walls, oriented more vertically than plastered, and the outer facade features a collection of numerous willow trees or sacred willow bushes, with their outer tips painted red. This is a fossilized version of various fuels or dry grass still piled around the rooftops of rural Tibet. The walls are adorned with a layer of lime wash or red ochre, regularly refreshed by pouring water from above. The rough texture of the outer surface in the adjacent residential buildings enhances the rustic, simple feel of the structure.

The internal wooden structure and wall surfaces are heavy with carvings and paint. The most important point in the complex is marked at the highest elevation by small golden roofs in the Chinese style crafted by Chinese artisans, complemented by golden net decorations originating from Indian artisans of Nepal, setting it apart from typical rural houses.

Fact Sheet:

-

Number of Floors: 13

-

Height: 117m

-

Materials: Stone, Wood, Mud

-

Elevation: 3,700m