In recent times, the emergence of cases of meningitis, including those caused by Neisseria meningitidis, also known as meningococcal meningitis (MM), in several southern provinces has caused panic in the community.

Recognizing Meningococcal Meningitis

This is an infectious disease in humans that can become epidemic, especially in children and young people. The disease has a high mortality rate if not detected early and treated properly.

|

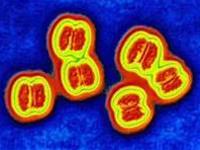

| Image of Neisseria meningitidis (Photo: TTO) |

The disease spreads through respiratory droplets, and to a lesser extent, it can be transmitted through contact with hands or personal items contaminated with bacteria from the patient’s bodily fluids. After recovery, the patient has immunity to the specific serotype of Neisseria meningitidis, but this immunity lasts only for about 2-3 years, and individuals can still be reinfected or infected with a different serotype.

After invading the upper respiratory tract cells, it causes pharyngitis, leading to symptoms such as cough, high fever, muscle pain, headaches, nausea, and in some cases, seizures, decreased muscle tone, paralysis of limbs or facial muscles, and altered consciousness. From the upper respiratory tract, the bacteria can further invade the bloodstream through the lymphatic system, reaching the brain or other organs such as joints and the pericardium, causing inflammation and pain in these areas.

Depending on the site of invasion, the virulence of the bacteria, and the body’s resistance, it can lead to mild pharyngitis to severe sepsis or even death. The mortality rate of meningococcal meningitis is between 5-10% of cases, often leaving severe neurological and aesthetic complications.

Current Status of Meningococcal Meningitis in Our Country

Meningococcal meningitis is reported across all regions of our country, predominantly in the North, especially during the winter-spring and late autumn-early winter seasons, due to the cold and humid weather coinciding with the season for other bacterial and viral infectious diseases. In the South, the disease is less common, with cases typically increasing from May to July. The disease is most prevalent among children and young people living in crowded dormitories, schools, training camps, or densely populated areas with poor sanitation.

To date, the mandatory surveillance and reporting system of the Ministry of Health has only identified cases of meningitis in general, often referred to as meningitis syndrome, without differentiating between the various causes, including meningococcal meningitis.

In the last months of 2005 and early 2006, the number of reported meningitis syndrome cases showed a slight increase compared to the same period the previous year across the country. On average, the Northern region reported 20-30 cases of meningitis per month during this time. At the Central Children’s Hospital and the Institute of Tropical Medicine, more than 100 cases were reported in the first 11 weeks of 2006, primarily among children.

In the southern provinces, the average reported cases of meningitis syndrome ranged from 5-10 cases per month, with 20 cases reported in February alone, including a fatality. In March, meningitis and encephalitis cases emerged in the South, possibly caused by enteroviruses.

Although the number of meningitis cases has increased recently, it has not reached epidemic levels, as most cases are dispersed locally. The number of meningococcal meningitis cases is limited to just a few instances. This further confirms that both encephalitis in general and meningococcal meningitis specifically have not emerged as an epidemic.

The recent increase in cases is primarily attributed to unusual climatic conditions during this year’s winter-spring, which are not favorable for human health. The South is currently in the dry season, but after the Lunar New Year, there have been several bouts of unseasonal rainfall, creating conducive conditions for the bacteria to thrive. Additionally, this is a time of significant population movement between regions due to festivals and tourism.

Tests have shown no changes in the biological, chemical, or virulence characteristics of the bacterial strains from the samples collected.

How to Limit the Increase of Cases?

Preventive health agencies need to enhance surveillance of patients with meningitis-encephalitis syndrome, particularly in areas where meningococcal meningitis cases have been confirmed. Meningitis can be caused by various agents; therefore, alongside diagnosing the disease based on clinical symptoms, it is crucial to collect specimens such as throat swabs, blood samples, or cerebrospinal fluid and send them to laboratories for identification of the cause. If a case of meningococcal meningitis is detected, prompt measures must be taken to contain and extinguish the outbreak as quickly as possible.

For the public, it is essential to maintain hygiene practices and keep the living environment clean, as the pathogens causing meningitis can be transmitted through respiratory droplets, the digestive tract, or contact with contaminated objects. Specifically, regarding meningococcal meningitis, in addition to regular environmental sanitation measures, it is necessary to maintain oral hygiene and care for the throat.

If respiratory infections present symptoms of meningococcal meningitis, patients should be taken to healthcare facilities immediately. If meningococcal meningitis is confirmed in a community, gatherings should be limited, and everyone should wear masks to prevent infection. Additionally, emergency prophylactic antibiotics may be administered according to a doctor’s instructions.

Currently, vaccines for meningococcal types A and C are available, but their protective duration is short (2-3 years) and they are relatively expensive, so they are only used for those living in high-risk areas.