(Reader) – The Archimedes’ principle states: “An object immersed in a fluid is buoyed up by a force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. This force is called the buoyant force.”

Archimedes’ principle is the foundation of buoyancy theory, taught for many generations. This principle was formulated over 2300 years ago. The phenomena and experiments discussed in the following article illustrate the need for further exploration of the following aspects of the principle:

1 – There are only two forces: P is the weight of the object and Fa is the force exerted by the fluid on the object.

2 – These two forces “push” against each other.

3 – Because they “push” against each other, when not balanced, they create a “torque.”

4 – An object floats when Fa > P.

V…..V

First: There are more than two forces acting on the object

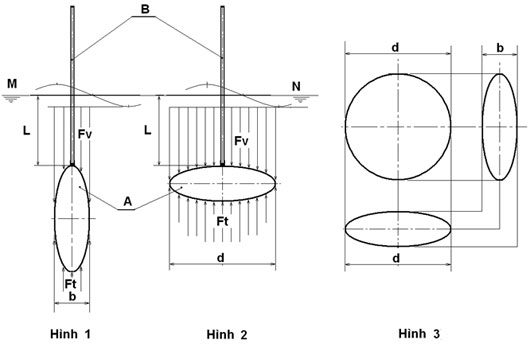

There are multiple forces acting on an object submerged in a fluid, which have not been addressed, as shown in the following case: Figures 1 and 2 describe two floating objects consisting of two components: A, which is shaped like a hollow disk (Figure 3 is the projection of A), and B, which is a tube. When component B is assembled into A, component A in two different positions creates two distinct floating objects 1 and 2, but both have the same water displacement:

Floating object 1 (Figure 1) has the disk face A positioned perpendicular to the fluid surface.

Floating object 2 (Figure 2) has the disk face A positioned parallel to the fluid surface.

The tube B connects to A to adjust the submerged depth of the object in tube B.

When external force is applied, both floating objects are pressed (or lifted) to the same depth. Observing the diagrams, it becomes clear that when the external force stops, the two objects float up at different speeds, leading to different time intervals. This difference is referred to as “delay”. So, which force creates the “delay”? This indicates that there are not just two forces acting on the object submerged in the fluid.

This type of floating object can be named “VN-A floating”, or “tube floating,” “suspended floating.”

Let the resisting force Fa be Fv, which slows the floating object down.

Let the resisting force P be Ft, which slows the sinking or falling speed of the floating object.

The forces Fv and Ft create differences in floating time, resulting in “delay.”

The characteristic of having “delay” is extremely important when the “VN-A floating” object is in a wave environment (hydrodynamics), such as at sea. This creates the ability to dampen the oscillation of the floating object in rough waves. It results in a “static floating” object in waves but still rising and falling with the tides, which is a type of floating that is highly desirable in life.

Second: It is not the “buoyant force” acting on the object

The principle asserts that two forces “push” against each other, meaning that forces P and Fa are in opposite directions, leading to:

– When the two forces are aligned on a straight line, they push against each other.

– When the two forces are not aligned, they create a “torque.” This conclusion is taught in university programs concerning a floating object (e.g., a boat) when the buoyant force Fa is not aligned with the weight P of the floating object.

This indicates that determining whether it is not a “buoyant force” but another type of force, meaning it is not a “torque,” becomes necessary.

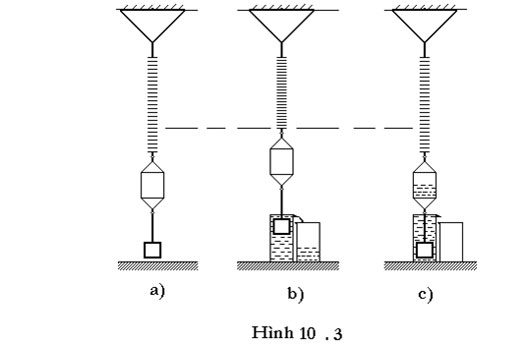

The experiment described in the 8th-grade textbook demonstrates the magnitude of the “BUOYANT” force in the principle as follows:

1 – (Figure 10.3a) Below a hanging scale is a container A, followed by a weight P, and the scale reads P1.

2 – (Figure 10.3b) The weight is submerged into an overflow container B filled with water, causing water to spill out, and the scale reads P2.

3 – (Figure 10.3c) The spilled water returns to container A, and the scale returns to P1.

From the experiment of submerging an object in a fluid, the object loses a portion of its weight, which is assumed to be “pushed,” is insufficient because the volume of the spilled water only indicates:

1 – The volume of the object.

2 – The weight of the displaced water must always equal the weight of the object that has been lost.

However, the direction of the force and where the buoyant force originates is crucial; since both the object and the water are under the influence of gravity, the two gravitational forces cannot push against each other. “An object immersed in a fluid is buoyed up by the fluid…”. If this were the case, it would present a paradox, while there might be other more reasonable possibilities, such as:

It may be that the object “presses” or “compresses” against the fluid (just like two solid objects pressing against each other), and because the fluid lacks sufficient “rigidity,” the object sinks into the fluid until its weight equals the weight of the fluid it displaces; if it exceeds, it will sink to the bottom while the fluid “presses” against it…

It is also possible that it is “suspended” in the fluid, and if its weight is greater than the weight of the fluid it displaces, then the “suspending line” will break, causing it to fall to the bottom of the fluid. If its weight is less, it will be suspended on the surface of the fluid, and when equal, it can be suspended at any position within the fluid, which is called suspension.

If that is the case, it would align with the theoretical principles of resultant forces and force analysis, no longer presenting a “paradox.” Therefore, to prove whether the force exerted by the fluid on the floating object is indeed a “buoyant force” or not, one must determine whether the two forces are indeed “torques.” If they are not “torques,” then they cannot be “buoyant forces.”

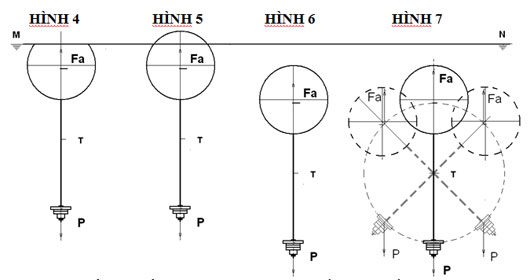

It is easy to see that any object submerged in water has its weight P always within the volume of the fluid being displaced, which is Fa, so the center of torque T also lies within Fa.

Thus, if there is doubt that it is not a “BUOYANT” force, one must “see” if the two forces are indeed “torques” by moving T outside of Fa, far enough that if it is a torque, Fa must rotate around T like P but in opposite directions.

Looking at Figures 4, 5, 6, and especially Figure 7, when Fa in Figure 6 rotates around T as per the torque model, we can see that it cannot occur at the center T. With this model, it is easy to conduct experiments to verify the following conclusions:

1 – The interaction between the two forces P and Fa is not a “torque” but a “moment” where P is the applied force, Fa is the point of application, and the distance between P and Fa is the length of the moment arm.

2 – As P and Fa are moments, it follows that:

“An object submerged in a fluid has its weight (P) suspended in, above, or below the volume of fluid (V1) it displaces.”

When observing a floating object (on the surface of the fluid) and calling the volume of the fluid displaced V1, the remaining volume of the floating object, the portion above the surface, is V2. This means we are observing the floating object in terms of volume.

From this perspective, it is clear that within a floating object, there are always two volumes with two different states of buoyancy. Hence, we see that:

When V2 > 0, the object is floating.

When V2 = 0, the object is in suspension.

When V2

When observing a floating object in terms of volume, it will be apparent that the traditional buoyancy principle is formed from a random floating method, thus the two volumes are like a pair of conjoined twins that cannot be separated, forcing volume V1 to be suspended directly under V2, hence it must lie in the most turbulent environment together with V2. While it is simply necessary to separate the two states and place them in their advantageous positions, to mitigate the impact of waves and effectively exploit the advantages of each state that nature has created?

Can a static floating object be created that is unaffected by waves in a hydrodynamic environment, such as the ocean, by separating the two volumes?

Can the two volumes be separated, repaired, and modified in their floating methods?

The VN-A floating principle has provided answers and guidance on how to create a static floating object by separating the two volumes, establishing a different type of floating compared to traditional floating methods from ancient times to the present. It may also be that this type of floating has been known but not fully utilized for its superior features. Additionally, this floating type indicates that buoyancy theory has not addressed other forces, focusing solely on the two forces acting on a floating object is insufficient!

Thinh Hao