In September 2012, Michael Rhodes, a technician at the United States National Declassification Center (NDC), was chosen to publicly disclose an important document – the “Final Development Summary Report of Project 1794 from April 2 – May 30, 1956.”

Rhodes’s job was to read these documents, catalog them, and provide them to historians, journalists, and the curious.

He quickly realized that the container of documents was quite unusual. Rhodes stated: “While handling the document set, I noticed this strange red flying saucer symbol in the corners.” Inside the box were numerous oddities: cutaway diagrams of a disc-shaped aircraft, charts showing drag and thrust performance at speeds exceeding Mach 3 (1,029 m/s), and black-and-white photos of a Frisbee-shaped object in a supersonic wind tunnel. The symbol of a flying saucer on a red arrow was an obscure insignia in aviation design. What was unfolding before Rhodes’s eyes were the lost records of a flying saucer program developed for the U.S. Air Force (USAF) in the 1950s.

Neil Carmichael, the head of the declassification review division at the NDC, commented: “During the Cold War, the Army, Air Force, and Navy of the United States experimented with all sorts of things. When the NDC released its declassified documents, Project 1794 was considered the most sensational material ever.”

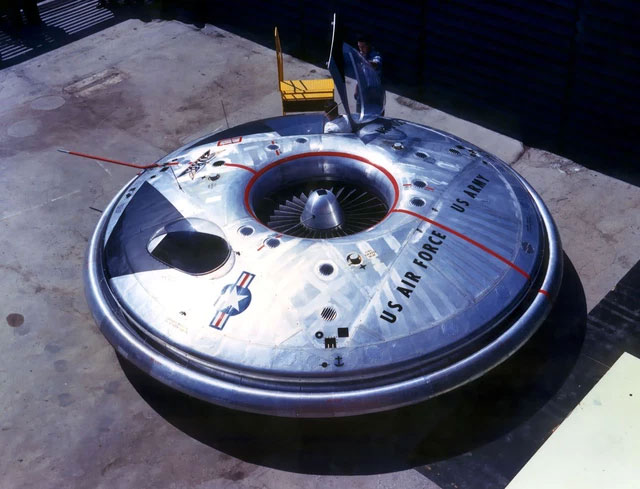

Accordingly, a Canadian aerospace company – Avro Aircraft (Avro Canada) began developing a disc-shaped aircraft for the U.S. military in the mid-1950s. This document refers to the Air Force’s “high-speed, vertical take-off” craft in 1956 and published a few photos in 1960 before the project was officially suspended. In popular culture, flying saucers have always been seen as a symbol of extraterrestrial life. However, what the documents disclosed by Rhodes reveal is that they actually originated from Ontario, Canada. That is where visionary aerospace engineers at Avro Canada actually built the flying saucer – the Avro Canada VZ-9 Avrocar.

Previously, Avro Canada had hired John “Jack” Frost in 1947, leveraging the talents of this 32-year-old man for the development program of a supersonic aircraft named Avro Arrow. While working on the Arrow program, Frost conducted experiments in the Avro laboratory on how airflow tends to adhere to slightly curved surfaces, producing a phenomenon known as the Coandă effect. The results indicated that the engine exhaust could be directed through the aircraft’s body to the area just below the disc, where it would create an air cushion on which the craft could hover.

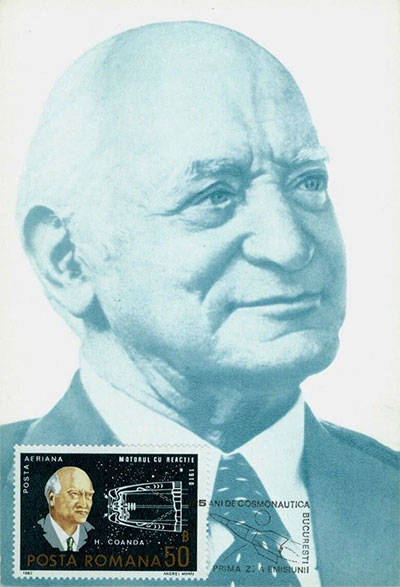

The Coandă effect is a property of fluid flow when it comes into contact with a convex surface. The property is named after Romanian inventor Henri Coandă, who was the first to discover its practical application and laid the groundwork for the development of aircraft and air conditioning systems later on.

After Frost discussed his laboratory research results with Omond Solandt, head of the Canadian Defence Research Board, in 1952, the Canadian government provided initial funding but later abandoned the project as it became too expensive.

Subsequently, Avro Canada proposed the project to the U.S. government, and the Army and Air Force took it over in 1958. However, the purpose of this project changed slightly: the military wanted to use it as a reconnaissance and subsonic troop transport vehicle that could operate in all terrains, while the U.S. Air Force wanted a vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft that could hover under enemy radar and then accelerate to supersonic speeds. Avro’s designers believed they could meet both requirements, but the two groups’ demands were too different.

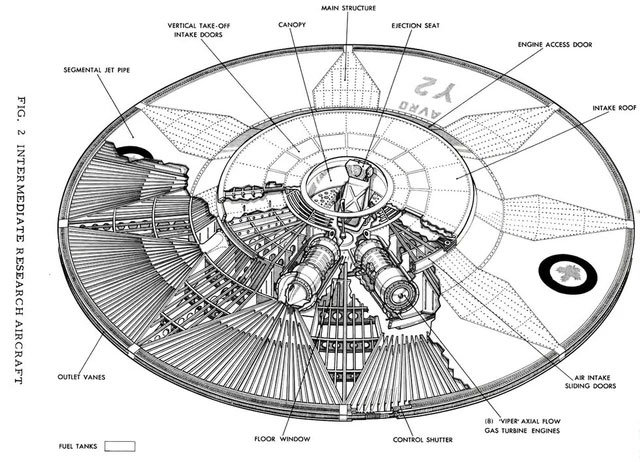

Accordingly, Frost’s design of a disc-shaped aircraft was detailed in a 117-page report – the same document that the NDC later uncovered. The proposed craft featured a central turbine, called a turborotor, powered by six jet engines. The turborotor engine drew air through the aircraft’s body. The exhaust was expelled from vents placed along the circumference of the aluminum disc; vanes and flaps directed the exhaust downwards to achieve lift.

Engineers predicted that the 20,000-pound (over 9 tons) thrust generated by the jet’s exhaust could be directed downward around the perimeter of the disc. The report stated: “The jet configuration around this wing creates a powerful take-off cushion so that the lift on the aircraft can increase to tens of tons.” Once airborne, the pilot of the flying disc would steer the exhaust to the side to maneuver. Frost anticipated that the disc would travel at Mach 4 and could reach an altitude of over 30 km. With this potential, the Air Force and Army agreed to fund prototypes, and Avro tasked Frost with establishing a secret facility for construction and testing. The Special Project Group (SPG) was located at the Avro plant in Malton, Ontario, northwest of Toronto.

Initial research data indicated that the circular wing could meet the requirements of both the Army and Air Force, and Avro built two small test vehicles to demonstrate its design. Tests with scale models at Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio indicated that the air cushion beneath the Avrocar would become unstable just 1 meter above the ground. At the same time, the flying disc was also unable to achieve supersonic speeds, but testing continued to determine whether a suitable aircraft for the Army could be developed.

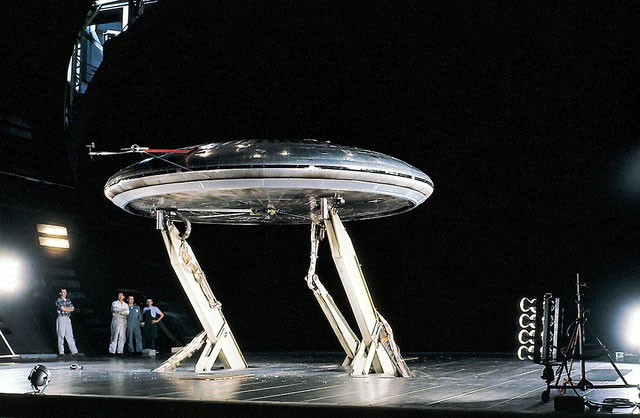

The first prototype – Avrocar 58-7055 was later sent to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) research center at Moffett Field, California, for testing in the supersonic wind tunnel to see if the flying disc was controllable for high-speed flight. However, tests showed that maintaining aerodynamic stability of the flying disc was very challenging. The hot exhaust air swirling underneath caused the frame structure to be susceptible to thermal deformation.

By April 1961, test flights resumed after several design improvements. In this round of testing, the flying disc achieved a maximum speed of about 190 km/h, three times faster than the previous speed of only 56 km/h, but engineers still could not maintain aerodynamic stability of the flying disc, leading the Pentagon to officially cease funding for the project.

According to some sources, the total amount spent by the U.S. Department of Defense on this project reached $10 million, equivalent to about $80 million today. Although Project 1794 was a failure, it still laid the groundwork for the later development of hovercraft. The prototypes of the two Boeing YC-14 and McDonnell Douglas YC-15 were later based on the project’s research. Notably, the central lift fan system of the F-35B vertical take-off version is believed to have also applied some technologies from the program.