The ancient bricks of Mesopotamia reveal an unusually strong magnetic field in what is now Iraq, dating back 3,000 years.

The fired bricks inscribed with the names of ancient Mesopotamian kings are undoubtedly treasures due to their age and craftsmanship. However, scientists have recently discovered that they are even more valuable because they hold secrets about ancient magnetic anomalies.

According to Live Science, the research team led by Professor Mark Altaweel, an expert in Near Eastern archaeology and archaeological data science at University College London (UCL), examined iron oxide mineral grains from 32 Mesopotamian clay bricks.

Most of these bricks were excavated in what is today Iraq, making them incredibly valuable artifacts.

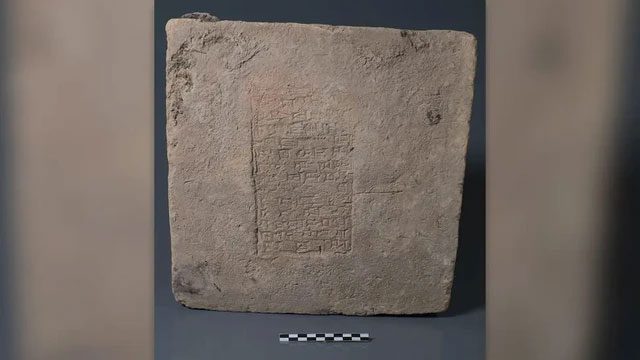

An ancient Mesopotamian brick hiding secrets about magnetic anomalies – (Photo: SLEMANI MUSEUM).

Each brick is engraved with the name of one of the 12 kings of Mesopotamia during their reigns. These inscriptions allowed scientists to specifically date each brick, with the oldest being over 3,000 years old.

The iron oxide minerals within the clay are highly sensitive to magnetic fields. Therefore, when the bricks were heated during the firing process, they inadvertently became a “time capsule” that preserved distinct characteristics of the Earth’s magnetic field.

This led scientists to find evidence supporting the hypothesis of “Iron Age Magnetic Anomalies in the Levant.”

The Levant refers to a vast region in the eastern Mediterranean that was once very fertile and became a cradle for some of humanity’s oldest civilizations.

During the period from 1050 to 550 BC, the area now known as Iraq experienced a “remarkably strong” Earth’s magnetic field, as described by scientists.

However, they have yet to explain why this magnetic anomaly existed in this region.

Other magnetic anomalies noted in ancient times occurred in distant places, including China, Bulgaria, and the Azores in the North Atlantic. Nonetheless, evidence of magnetic anomalies in the Middle East remains quite rare.

Additionally, the most significant magnetic changes recorded occurred in five samples from the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II of the Chaldean dynasty of ancient Babylon (around 604 to 562 BC).

“The geomagnetic field is one of the most mysterious phenomena in Earth science. The archaeological evidence clearly dated to Mesopotamian culture is rich, providing an opportunity to study magnetic changes over time with high accuracy,” said Professor Lisa Tauxe from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, a co-author of the study.

Regardless of the discoveries made, today’s magnetic anomalies remain a significant puzzle, both in terms of how they arise and disappear, as well as their impact on the planet.

Among them, a vast magnetic anomaly currently spans from South America across the ocean to Cape of Good Hope in Africa, leading scientists to even predict that the Earth may soon undergo a magnetic pole reversal.