The unique geography, natural disasters, and electricity market structure are factors preventing Japan from keeping pace with other countries in the transition to renewable energy.

After the tsunami led to the meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2011, both Japan and Germany undertook radical changes in their energy policies. Japan shut down its nuclear power industry and compensated for much of the electricity shortfall with coal. Germany, on the other hand, announced a slower phase-out of nuclear energy, supported by wind and solar power. Twelve years later, the differences between the two countries are stark.

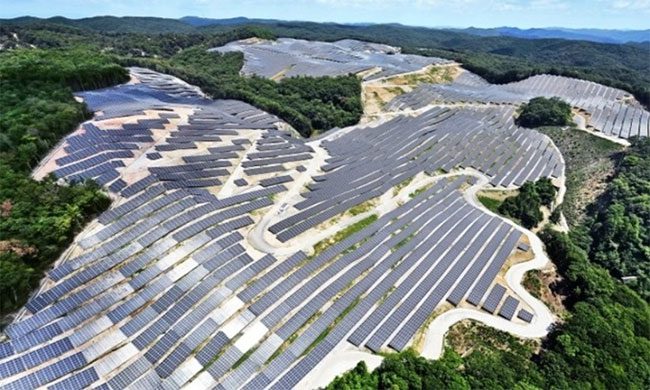

Solar farm at a former golf course in Kamigori, Hyogo. (Photo: Toyokazu Kosugi)

In Germany, the explosive growth of renewable energy boosted the carbon-free electricity share in the power sector to 58% last year. Per capita emissions decreased by 21% compared to 2010, while the country’s GDP grew by about 14% per person.

Japan is lagging behind in almost every aspect. Contrary to other developed countries, the share of fossil fuel energy in Japan’s electricity grid has increased over the past decade, while the carbon-free share dropped to 28%. Emissions only decreased by 8.6% while GDP rose by over 9.4%. Before the Ukraine conflict disrupted Germany’s gas supply from Russia, the Japanese were even paying more on their electricity bills. So why is a country that once hosted the signing of the Kyoto Protocol on emission reductions, the nation that invented lithium-ion batteries, hybrid cars, and solar-powered computers, falling so far behind?

The answer is not confined to a single reason but rather combines several seemingly insignificant factors that, when grouped together, become formidable obstacles. Part of Japan’s problem lies in its geography. Renewable energy requires a lot of space, but Japan’s mountainous terrain means that usable land is very scarce. The agricultural land that sustains 126 million people, the most suitable for renewable energy, is hardly larger than the island of Ireland or the sparsely populated country of Guatemala.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that 1/5 of farmland and 11% of Japan’s total area is unregistered. Due to inheritance laws, large tracts of land remain under the names of deceased individuals for generations. Economies of scale play a crucial role in reducing the costs of wind and solar projects, but this is only feasible if developers can consolidate multiple parcels of land with known ownership. This is nearly impossible because it’s hard to know who owns the land. Japan’s two largest onshore solar farms were previously reclaimed land used for salt flats and shipyards. However, such sites are not abundant.

Earthquakes and typhoons also mean that large-scale construction projects need to be built to withstand extreme natural disasters. Class 3 wind turbines, which are relatively lightweight and popular in most countries, are rarely used in Japan due to the risk of being destroyed by strong winds.

However, the biggest factor might be the structure of the electricity market. Japan does not have a national grid like most other countries. Instead, the country has ten separate companies corresponding to historical regions, each operating independently. A developer wishing to harness surplus solar power in Kyushu to supply renewable energy to Tokyo must negotiate with five separate entities to ensure adequate power transmission infrastructure is in place to deliver electricity to where it’s needed. Traditionally, these entities are integrated companies owning everything from power generation to transmission lines and retail electricity. This organizational structure gives them little incentive to work with startup renewable energy companies that could threaten their current business model.

The result is that Japan is one of the few places in the world where renewable energy still struggles to outperform fossil fuel-based electricity. The cost of onshore wind power in Japan is three times that in Brazil, China, India, and Spain, making it almost absent from the market. Solar power has decreased to below $100 per megawatt hour in the past 12 months, a price level that most other developed countries reached by the middle of the last decade. This means that solar power could eventually compete with new coal plants on price, but it is still more expensive than using fossil fuel-powered generators.

According to Japan’s latest energy plan, by 2030, the country will still derive 41% of its electricity from fossil fuels. If local residents continue to oppose the restart of nuclear reactors and electricity demand does not decline rapidly, fossil fuel-powered turbines could account for 60% of production by 2030, similar to Germany in 1990.