The laws in ancient China were extremely strict, with a special Ministry of Punishments responsible for enforcing penalties. When we think of the brutal and inhumane punishments of ancient times, we often associate them with beheading, dismemberment, and lingchi (death by a thousand cuts), but these were not the most catastrophic forms of punishment.

Tru di cửu tộc, or the punishment of exterminating nine generations, is perhaps the most familiar punishment due to its frequent portrayal in Chinese historical dramas, where it is applied to those who offend royal power, rebel, or commit acts against the Emperor.

The Origins of the Tru Di Punishment

The Tru di punishment was typically applied to the gravest offenses, including: “colluding with the enemy” (treason, consorting with the enemy), “insulting the emperor” (deceiving the emperor, offending the royal family), “conspiring to rebel” (plotting insurrection), and “heinous crimes” (serious offenses).

This form of punishment aimed to eradicate future threats and root out the influences of the criminal along with their family members, while also reinforcing the supreme authority of the Emperor. The primary methods of execution in the Tru di punishment included lingchi or beheading.

The Tru di punishment was usually applied to the gravest offenses.

The Tru di punishment is believed to have originated during the Shang Dynasty in Chinese history. At that time, it was referred to as “er dian,” which meant executing the criminal along with their children.

During the Qin Dynasty, the Tru di punishments became even harsher under Emperor Qin Shi Huang, expanding to cover “three clans” (3 family lines), “five clans” (5 family lines), and “seven clans” (7 family lines). Under the Han Dynasty, although the Tru di punishment was still inherited, it became more lenient. In many cases, emperors would revoke the sentences, resulting in far fewer executions compared to the Qin Dynasty.

However, in the late Eastern Han Dynasty, Tru di punishments occurred more frequently due to the power of the emperors largely falling into the hands of powerful officials, with notable cases being the Tru di of Dong Zhuo and Dong Cheng, ordered by the powerful officials Wang Yun and Cao Cao.

The Tru di punishment extended into the reign of Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty. In the Tang Dynasty, it was only applied to those who conspired against the emperor’s rule, targeting the parents, children over sixteen, and other close relatives.

By the time of the Ming Dynasty, instances of Tru di became more common. The Tru di punishment during the Qing Dynasty was a direct imitation of the regulations from the Ming Dynasty. This brutal punishment was only officially abolished in 1905, at the end of the Qing Dynasty.

This brutal punishment was only officially abolished in 1905.

There are various theories regarding the definition of “three clans.” Some believe “three clans” refers to parents, siblings, and spouse. Others suggest it means father, mother, and wife. There are also interpretations that view “three clans” as father, child, and grandchild.

“Nine clans” also has multiple interpretations, but it is generally understood to refer to nine family lines according to the Zhou Dynasty: Parents, siblings, sons and daughters; maternal aunts; children of sisters; grandchildren; maternal grandparents; paternal grandparents; paternal aunts; father-in-law; mother-in-law.

Notable Instances of the Tru Di Punishment in Chinese History

Many believe that Tru di cửu tộc is a common punishment due to its frequent mention in television dramas, but in reality, very few people were actually subjected to this punishment in history. The most notable cases are as follows:

In reality, very few people were actually subjected to Tru di cửu tộc in history.

The first was Yang Xuan Gan of the Sui Dynasty. He was born into a family of officials. His father, Yang Su, served in the Sui court and helped Emperor Yang gain the throne and quell the rebellion of the Han Prince Yang Liang, being a great contributor to the dynasty.

However, after Yang Su’s death, Yang Xuan Gan inherited his position and was promoted to Minister of Rites. At this time, Emperor Yang’s suspicions grew, and Yang Xuan Gan began to harbor thoughts of disobedience. During Emperor Yang’s second war against Goguryeo, he was unexpectedly betrayed by someone close to him.

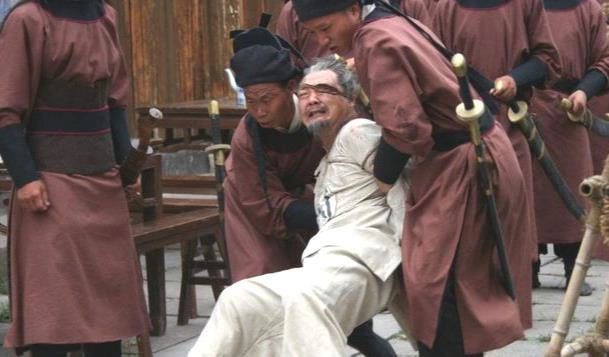

Yang Xuan Gan took this opportunity to rebel but underestimated the strength of Emperor Yang. While Emperor Yang was fully engaged in the frontline battle, he had to return to the capital and quickly suppress Yang Xuan Gan’s rebellion. After capturing Yang Xuan Gan, Emperor Yang was filled with hatred and tortured him in every possible way.

Simultaneously, Emperor Yang punished Yang Xuan Gan’s nine clans and changed his surname to “Jiao” as a form of punishment, as “Jiao” in pictographic writing represents the image of a person beheaded and displayed on a pole.

The second person subjected to Tru di cửu tộc was Fang Xiao Ru, a high-ranking official at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty. However, Fang Xiao Ru was not subjected to Tru di cửu tộc, but rather to Tru di thập tộc, implicating ten branches of his family.

After the Jingnan Campaign (a civil war in the early years of the Ming Dynasty between Zhu Yunwen and his uncle Yan Wang Zhu Di), Yan Wang Zhu Di took control of Nanjing, and Fang Xiao Ru became the leader of the group of high officials. To win Fang Xiao Ru’s support, Zhu Di employed all means at his disposal, threatening and enticing him.

However, Fang Xiao Ru was resolute and uncompromising, and in the end, Zhu Di became furious and said to Fang Xiao Ru: “Are you not afraid that I will exterminate your nine clans?”

Fang Xiao Ru replied: “Even if you exterminate ten clans, I am not afraid.” In a fit of rage, Zhu Di ordered the massacre of ten branches of Fang Xiao Ru’s family.

Why Did Relatives of the Criminals Not Flee?

With so many people in the family implicated, why didn’t they flee? In reality, it was not that they did not want to escape, but rather that they were “lazy” and did not dare to run away.

Therefore, many simply did not bother to escape, and even if they wanted to, they did not dare.

Firstly, the transportation was inconvenient. In ancient times, transportation was underdeveloped, and travel was very inconvenient, making it difficult to escape the imperial net: “The net of heaven is vast, though sparse, it is hard to escape.”

Secondly, there was nowhere to go. The household registration system in ancient times was quite complete. Thus, it was very challenging to move from one place to another without official documents. Entering and exiting city gates required passing through multiple layers of checks, making survival in another location nearly impossible even if one managed to escape the city.

Thirdly, there was a desire for death. Even if the accused escaped, their family members had already been sentenced to death; what benefit was there in remaining in the world alone?

Moreover, the ancient Chinese were influenced by the ideology that “If the king wishes for the subjects to die, the subjects cannot avoid death.” In a feudal society filled with tyranny, rather than thinking of the impossible escape, they preferred to seek ways to obtain the Emperor’s forgiveness, thus avoiding the disaster of death.