Researchers from the University of Copenhagen suggest that water appeared on Earth when the planet absorbed dust and ice during its formation.

Earth may have formed much faster than many previous hypotheses suggest, emerging as tiny pebbles a few millimeters in size that accumulated over millions of years. The new hypothesis also implies that instead of icy comets delivering water to Earth, this essential ingredient for life existed on the planet because young Earth absorbed water from the surrounding space environment. This conclusion has significant implications for the search for life beyond the Solar System, indicating that habitable planets containing water around other stars may be more common than previously thought. Isaac Onyett, a doctoral candidate at the Star and Planet Formation Center at the University of Copenhagen, and his colleagues published their research on June 14 in the journal Nature.

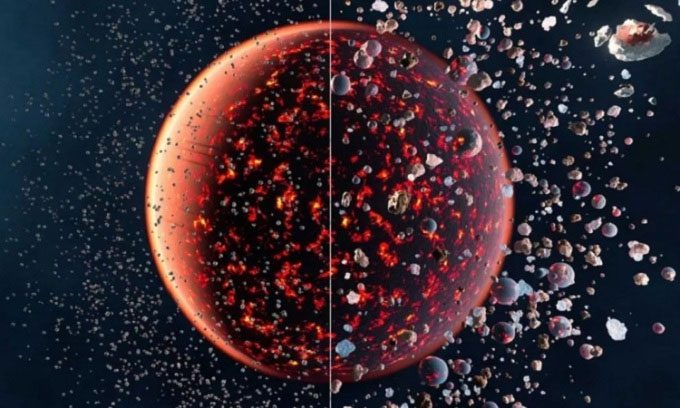

Simulation of Earth’s formation mechanism from small pebbles. (Image: UHT Zurich).

The researchers’ hypothesis indicates that about 4.5 billion years ago, when the Sun was still a young star surrounded by a disk of dust and gas, small dust particles were drawn in by forming planets as they reached a certain size. In the case of Earth, the process of absorbing material from the dust and gas disk ensured that the planet was provided with water.

This disk also contained many ice particles. As the dust absorption effect occurred, it also absorbed a significant amount of ice. This process contributed to the existence of water during Earth’s formation, rather than relying on a random event that brought water to the planet 100 million years later.

“People have debated how planets form for a long time”, said geochemist Martin Schiller from the University of Copenhagen, a member of the research team. “One hypothesis is that planets are born from collisions between multiple celestial bodies, causing their sizes to gradually increase over 100 million years. In that scenario, the emergence of water on Earth would require a random event.”

An example of such a random event could be icy comets containing water colliding with the planet at the end of the formation period. “If that were how Earth formed, our possession of water would be quite lucky. Thus, the chances of water existing on planets outside the Solar System would be very low,” Schiller shared.

The research team derived their new hypothesis by using silicon isotopes as a measure of planetary formation mechanisms and the associated timeline. By examining the isotopic composition of over 60 meteorites and planets, they were able to establish connections between rocky planets similar to Earth and other celestial bodies in the Solar System.

The new hypothesis predicts that if a planet orbits a sun-like star at an appropriate distance, it will have water, according to Professor Martin Bizzarro at the Globe Institute, a co-author of the study.