Restoring an ancient epic is a task that demands patience and a lengthy process. However, the emergence of AI has accelerated this restoration process.

Many scholars have endeavored to search for and restore fragments of the Epic of Gilgamesh—one of the oldest literary texts in the world. Currently, the involvement of AI brings a “dramatic acceleration” to this process.

When Was the Epic of Gilgamesh Discovered?

In 1872, while studying a dusty clay tablet at the British Museum, George Smith, a museum employee, unexpectedly stumbled upon words that could change his life. Written in ancient cuneiform, he discovered the story of a great flood from ancient times.

“I am the first person to read this after over 2,000 years of being forgotten,” Smith exclaimed with wild excitement. Smith recognized that the clay tablet was a small part of a much longer work—one that some believed could illuminate the Book of Genesis in the Bible.

Relief depicting Gilgamesh, displayed at the Louvre Museum. (Photo: Thierry Ollivier/Musée du Louvre).

This discovery brought fame to Smith, who came from a working-class family and largely taught himself cuneiform. He spent the rest of his life searching for missing fragments of poetry, making multiple trips to the Middle East before dying of illness during his final trip in 1876 at the age of 36.

In the 152 years since Smith’s discovery, successive generations of Assyriologists—experts in cuneiform script and the cultures that used it—have taken on the task of piecing together a complete version of the poem now known as the Epic of Gilgamesh.

The fragments of the epic, written over 3,000 years ago and based on earlier works, have re-emerged as excavated tablets from archaeological digs. They have been found in museum archives or appeared on the black market.

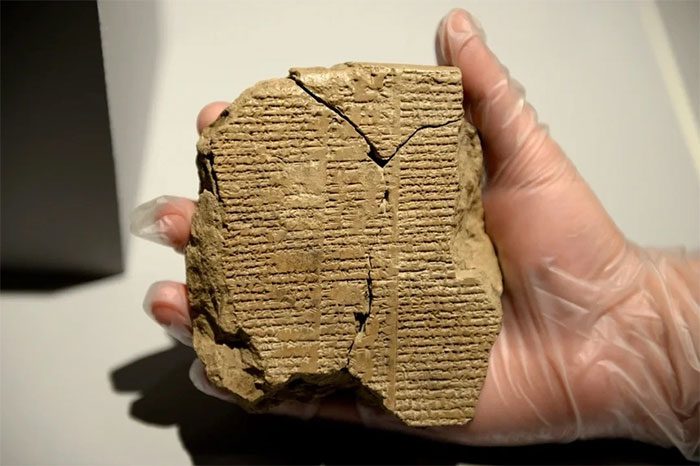

A fragment of the Epic of Gilgamesh on a clay tablet.

Hope with AI Involvement

Researchers face a daunting task. There are up to half a million clay tablets in collections regarding Mesopotamia at various museums and universities worldwide, along with many other broken tablet fragments. However, due to the shortage of cuneiform specialists, many of these tablets remain unread, and many others unpublished.

Consequently, despite the efforts of many generations, approximately 30% of the Epic of Gilgamesh remains missing, and there are gaps in the understanding of both the poem and the writing style of the Mesopotamians in general.

Fortunately, an artificial intelligence project called Fragmentarium is helping to fill in the missing gaps of the Epic of Gilgamesh. Led by Professor Enrique Jiménez at the Institute of Assyriology at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, the Fragmentarium team is digitally piecing together the fragments at a pace much faster than an Assyriologist could manage.

So far, AI has helped researchers uncover new sections of the Epic of Gilgamesh as well as hundreds of missing words and lines in many other works. Professor Andrew George, an honorary professor at the University of London and a leading authority on the Epic of Gilgamesh—who has personally completed one of its translations into English—stated: “This is a dramatic acceleration compared to what has been happening since George Smith.”

Before 2018, only about 5,000 fragments had been found. In the six years since, Jiménez’s team has successfully pieced together over 1,500 additional fragments, including pieces related to a newly discovered hymn about the city of Babylon and 20 fragments from Gilgamesh that add details to over 100 lines of the epic.

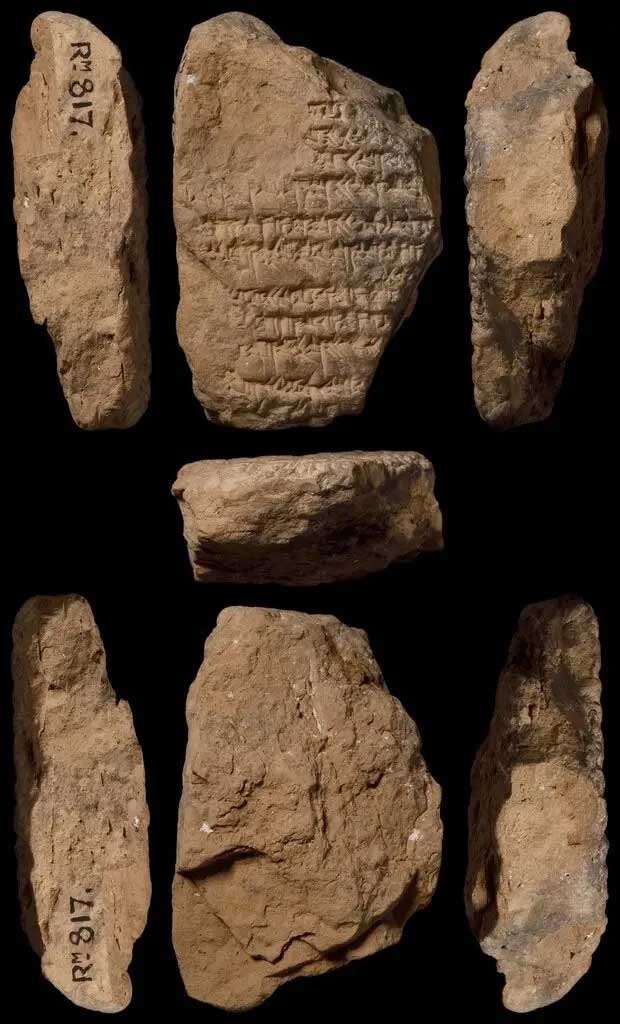

Many clay tablets preserved in museums, libraries, and other collections remain unidentified and undeciphered. (Photo: Enrique Jiménez).

The Story Reveals More Intriguing Details

Professor Jiménez noted that the Gilgamesh fragments provide more fascinating details about the story.

The focus of the epic is the tale of the friendship between Gilgamesh—a demigod and king of Uruk—and his wild companion, Enkidu. After Gilgamesh and Enkidu kill Humbaba (the guardian monster of the Cedar Forest), the gods kill Enkidu in revenge. Gilgamesh then refuses to bury Enkidu until after seven days, when a maggot falls from Enkidu’s nose.

“How can I be silent? When my beloved friend Enkidu has turned to clay. Am I to be like him, lying down, never to rise again, for eternity?” Gilgamesh repeatedly asks.

To escape the shadow of death, Gilgamesh embarks on a quest to find his ancestor Utnapishtim, a Noah-like figure who survived the great flood and learns the secret to immortality.

After some time, Gilgamesh finally finds Utnapishtim. However, the flood hero cannot grant Gilgamesh immortality. Instead, Utnapishtim shares the story of his life before and during the flood. The conclusion of the epic suggests that Utnapishtim’s wisdom and the knowledge he imparts are among the main rewards of Gilgamesh’s journey.

A few broken fragments from the British Museum that Professor Enrique Jiménez’s team has worked on. (Photo: The British Museum).

The newly discovered fragments with the help of AI reveal additional elements that add significant details to this story. For instance, one of them reveals that after killing the forest monster, Gilgamesh and Enkidu traveled to Nippur, the religious center of Mesopotamia and the home of the god Enlil. “They went there together, in an effort to appease Enlil’s anger for killing Humbaba, whom he had protected,” Professor Jiménez disclosed.

Benjamin R. Foster, a professor specializing in cuneiform and a translator of Gilgamesh at Yale University, stated that the new findings also reveal details about Enkidu’s efforts to persuade Gilgamesh not to kill Humbaba. Other lines recount Gilgamesh’s mother’s prayer to the sun god to touch Enkidu so that he could lead Gilgamesh through the Cedar Forest.

Some of these new findings have been included in the English translations of Gilgamesh by Sophus Helle (Yale University Press, 2021) and George (Penguin Classics, 2020). The most recent discoveries have yet to be published, but Jiménez’s team will soon present all the new works to the public as part of the Gilgamesh translation published in the Electronic Library on Babylon.

Helle is fascinated by how the epic continues to emerge. “It is very ancient but still very vibrant and constantly changing as I actually work with it. But that makes translation even more challenging,” the expert remarked.

Jiménez is optimistic that AI will allow researchers to draw more connections between these ancient types of texts. His team has completed work with the British Museum and is collaborating with colleagues at the Iraq Museum in Baghdad, where he hopes to find more fragments of the Epic of Gilgamesh.