A catastrophic event nearly shattered the evolutionary path of life on Earth.

An international study led by the University of Southampton (UK) has discovered that the harmful interaction between the oceans and continents once created a gigantic “hell” right here on Earth, which almost deprived many current species of the opportunity to emerge.

This event occurred approximately 185-85 million years ago.

According to the paper published in the journal Nature Geoscience, it was not a continuous event lasting 100 million years from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous periods, but rather a series of events, with one receding as another approached.

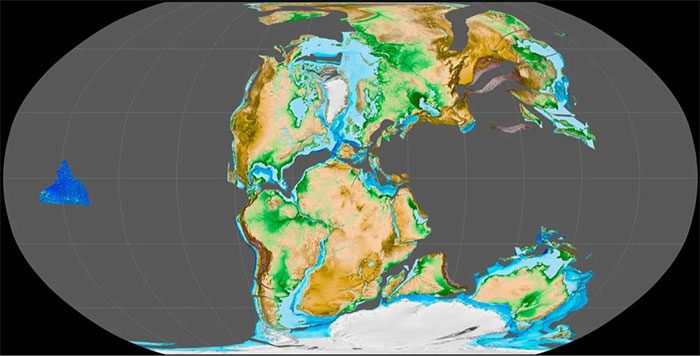

Map of the world during the Mesozoic Era, when Earth’s land was divided into two supercontinents – (Image: UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON).

During each of these events, the levels of dissolved oxygen in the global ocean suddenly dropped drastically, turning previously life-sustaining waters into a gigantic hell.

Many marine organisms were slaughtered in this “ocean hell” where breathing was impossible. But they were not the only ones affected.

“The oceanic hypoxia events act like a reset button for the planet’s ecosystems,” explained lead author Tom Gernon, a professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Southampton.

If luck had not been on their side, such events could have broken the evolutionary path of Earth’s organisms, leading to a true apocalypse or at least preventing the survival of most species present today.

The question is, what triggered that dangerous “reset” button?

The research team from the UK, Australia, the Netherlands, Canada, and the USA discovered that it was the continents themselves.

The researchers combined statistical analyses with complex computer models to explore how chemical cycles in the ocean might react to the disintegration of the southern supercontinent Gondwana.

During that time, Gondwana was teeming with dinosaurs, while the northern supercontinent Laurasia was much less populated.

The Mesozoic Era, encompassing the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous periods, witnessed the breakup of Gondwana.

However, from the late Jurassic to the mid-Cretaceous, this breakup intensified.

This caused intense volcanic activity worldwide.

As tectonic plates shifted and new ocean floors formed, a vast amount of phosphorus—an essential nutrient for life—was released from weathering volcanic rocks into the ocean.

“Importantly, we found evidence of multiple phases of chemical weathering occurring both on the ocean floor and on land, intermittently disrupting the oceans,” the authors noted.

The factors that once sparked the beginnings of life once again led to an excessive explosion of marine life.

This increase in biological activity resulted in a massive amount of organic matter sinking to the ocean floor, where it consumed large amounts of oxygen.

As a result, an ocean that was overly enriched with favorable conditions for life lost the very element that life needs to thrive: Oxygen. It became a land over-fertilized, where nothing could survive, turning into a true hell.

Ultimately, this process caused oceanic zones to become hypoxic or anoxic, creating dead zones where most marine organisms perished.

These hypoxia events typically lasted about 1-2 million years and had profound impacts on marine ecosystems, the traces of which can still be felt today.

Life on Earth is intricately connected, so terrestrial ecosystems were certainly affected as well.

Nevertheless, the Earth once again demonstrated its resilience after extinction events: When one thing dies off, another emerges to fill ecological niches.

This could even trigger leaps in evolution, resulting in the richness of species we see today.