When Mount Rainier erupts, the lava flow and ash are not the greatest threats to nearby communities; rather, it is the mix of water and volcanic rock moving rapidly from melting snow and ice.

Mount Rainier, standing at 4,300 meters in Washington State, USA, has not experienced a major eruption in the past 1,000 years. However, despite the bubbling lava fields in Hawaii or the supervolcano at Yellowstone, Rainier remains the most concerning volcano for American volcanologists.

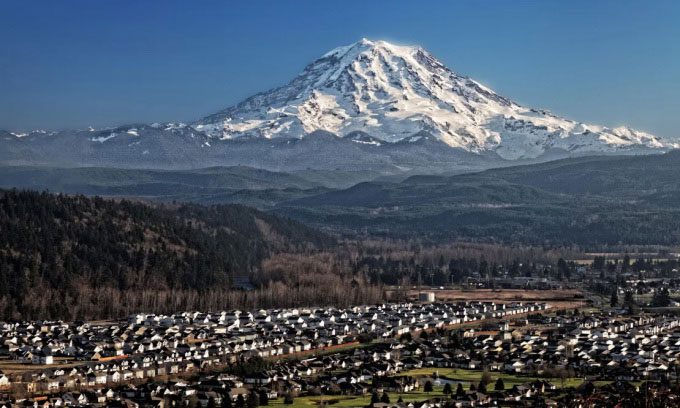

Snow-covered Mount Rainier stands majestically near Orting, Washington. (Photo: Ed Ruttledge/Cascades Volcano Observatory, USGS)

“Rainier keeps me awake at night because it poses a significant threat to the surrounding community. The Tacoma and South Seattle areas are built on a 30.5-meter-thick layer of ancient mud from Mount Rainier’s eruptions,” said volcanologist Jess Phoenix.

The danger of this “sleeping giant” does not lie in the hot lava, as, if it were to erupt, the lava would not flow more than a few kilometers from the boundary of Mount Rainier National Park. Most volcanic ash would also be dispersed by the wind to the east, away from populated areas, according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS).

Instead, many scientists are concerned about the potential for lahars – fast-moving mixtures of water and volcanic rock originating from melting snow due to volcanic activity, which can carry debris as they flow through valleys and drainage channels.

“What makes Rainier dangerous is its height and the snow and ice that cover it. Therefore, if any eruption occurs, the hot material will melt the cold material, and a massive amount of water will begin to pour down. There are tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands of people living in areas that could be affected by a large lahar, and that can happen quite quickly,” said Seth Moran, a seismologist at the Cascades Volcano Observatory, USGS.

The most dangerous lahar in recent history occurred in November 1985 when the Nevado del Ruiz volcano in Colombia erupted. Just hours after the eruption began, a river of mud, rocks, lava, and water swept through the town of Armero, killing over 23,000 people in just minutes.

The eruption of Nevado del Ruiz in November 1985 devastated the town of Armero, Colombia. (Photo: Jacques Langevin/Sygma).

Rainier has about eight times the snow and ice mass compared to Nevado del Ruiz at that time, according to Bradley Pitcher, an environmental science and Earth lecturer at Columbia University. “A much more catastrophic mudflow is at risk of occurring,” he noted.

A 2022 study simulated two worst-case scenarios. In the first simulation, a lahar with a volume of 260 million cubic meters and a thickness of 4 meters begins to flow down from the western slope of Mount Rainier. According to Moran, this mudflow would be equivalent to 104,000 standard Olympic swimming pools and could reach the densely populated lowlands of Orting, Washington, about an hour after the eruption. The mud would move at a speed of approximately 4 meters per second. In the second simulation, the Nisqually River valley would suffer similarly as a massive lahar could sweep water from Alder Lake, causing the 100-meter-high Alder Dam to overflow.

USGS established a lahar detection system at Mount Rainier in 1998, which was later upgraded and expanded in 2017. Approximately 20 sites on the volcanic slopes and two roads identified as having the highest risk of lahar are now equipped with broadband seismometers that transmit real-time data, along with various other devices such as trap wires, acoustic sensors, cameras, and GPS receivers.

This March, around 45,000 students from the Puyallup, Sumner-Bonney Lake, Orting, White River, and Carbonado areas in Washington participated in a lahar evacuation drill. According to USGS, this is the first time many schools from different areas have participated together, making it the largest lahar drill in the world.