Despite living in an age of scholasticism, when people regarded scriptures as the ultimate truth, Roger Bacon (1214 – 1294) left behind a statement that humanity will forever be grateful for: “All knowledge originates from practical experience.” Despite facing obstacles and imprisonment, he became an empiricist, seeking knowledge and truth through scientific methods.

The Rebellious Friar

Bacon was born in Ilchester, Somerset (England), and was quickly enrolled by his family in the prestigious Oxford University, where he became a teacher. In 1237, at the age of 23, Bacon was invited to teach at the University of Paris (France).

His expertise was in Aristotle’s philosophy, but beyond that, this young scholar was also interested in and proficient in many other fields such as arithmetic, geometry, Latin grammar, astronomy, and even literature and music.

For about the next ten years, Bacon taught at the University of Paris and interacted with many renowned scholars. In 1247, he left his position, and it is unclear where he went and what he did, but by 1256, he reappeared as a friar of the Franciscan Order.

It seems that during nearly a decade of absence, Bacon focused on researching optics based on ancient Greek and Arabic texts. In the following years, he dedicated himself to the study of religion.

Unlike typical friars who concentrated on doctrine, Bacon was only interested in forbidden subjects such as alchemy, witchcraft, and necromancy. Moreover, this friar compiled his findings and published books.

The Church was not pleased with Bacon’s activities, constantly obstructing and punishing him. In the 1260s, wanting to disseminate his research, Bacon sought a patron. In 1266, he received the tacit support of Pope Clement IV. Within just a year, Bacon wrote a series of epic works, becoming one of the most prolific writers of his time.

In 1268, Pope Clement IV passed away. Losing his patronage, Bacon was accused of blasphemy and heresy by the Church, imprisoned, and put under house arrest for two years.

The path to knowledge for Bacon involved repeated testing processes, observation, and documentation. (Photo: Justinas, Adobe Stock).

The Scientific Researcher

In one year under the patronage of Pope Clement IV, Bacon wrote about a million words, producing four epic works: “Opus Majus,” “Opus Minus,” “De Multiplicatione Specierum,” and “De Speculis Comburentibus.” Among them, the most notable is “Opus Majus.”

Unlike typical epic works, “Opus Majus” is a compendium of Bacon’s research and insights on mathematics, optics, alchemy, and astronomy. It represents the author’s views on fields that contemporary academia had not emphasized, particularly those beneficial to life such as agriculture, medicine, and experimentation.

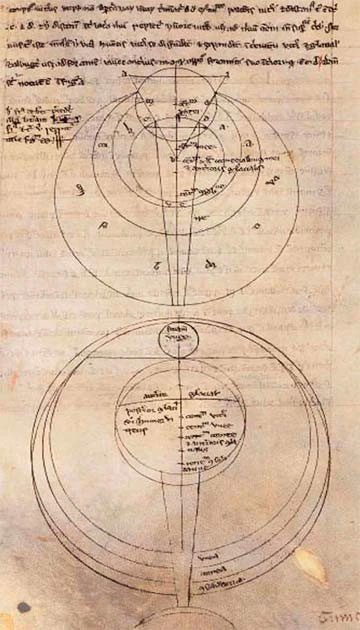

During the medieval period, religious texts were considered encyclopedic. The Church suppressed and did not recognize scientific or heretical writings. With ten years of research in optics, Bacon discovered refraction, the speed of light, spherical aberration, and more, paving the way for future discoveries and contributing to the development of glasses, microscopes, and telescopes.

After a journey to the Mongol Empire with a group of Franciscan friars, he brought back a formula for gunpowder consisting of saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur. Although Bacon did not personally make gunpowder, the formula he documented spread throughout Europe, laying the groundwork for future breakthroughs in weaponry such as cannons and firearms.

Throughout his life, Bacon was fascinated by alchemy. He was intrigued by the transformation of metals and aspired to create an elixir that could cure all diseases and prolong life. Instead of secretly practicing like contemporary witches and sorcerers, Bacon conducted his experiments openly. He believed that alchemy was a systematic scientific process involving experimentation, observation, and documentation, rather than relying on divine or demonic assistance.

Through diligent experimentation, observation, and documentation, Bacon continually made new discoveries. He recognized the importance of measurement, accuracy, and record-keeping in experiments. Gradually, Bacon successfully developed a new distillation method. His chemical experimentation processes are still employed by laboratories today.

The Master Linguist

A diagram by Bacon on optics. (Photo: Justinas, Adobe Stock).

The deeper Bacon researched, the more he believed in the power of experimentation. He declared that the origin of knowledge is experience, which is distilled through many experiments. No matter what it is, humans can only draw the most accurate conclusions based on experience. Today, we refer to his way of thinking as empiricism.

According to Bacon, the most effective means of conveying experience is language. He was particularly interested in the function of sentences, emphasizing that grammatical rules are essential standards for writing texts and explaining phenomena, leaving behind a treatise on Latin grammar.

Bacon was also the first to recognize that a word can have multiple meanings and that the semantics of a word depend on its context of use. He emphasized the importance of using precise and clear terms, detesting vague expressions.

Bacon’s study of language made the Church feel threatened. For centuries, controlling written texts was one of the methods used by the Church to maintain its power.

In addition to popularizing methods for understanding texts, Bacon also exposed the exploitative aspects of ambiguous meanings in many religious documents, revealing deceptive tactics used to brainwash followers. Thus, he became despised by the Church and hostile friars.

Beyond challenging traditional thinking, Bacon’s ideas paved the way for new concepts and approaches. His demand for “reason and evidence” strongly refuted superstition and dogma, laying the groundwork for establishing research principles based on scientific methods that humanity would apply indefinitely in the future.