A very small portion of the population has a natural ability to resist HIV, and scientists want to understand why.

Now, a group of international researchers has discovered a new set of genetic variants among individuals of African descent, and these genetic variants appear to limit the replication of HIV once infection has begun.

While further research is needed to confirm these findings, they represent a significant advancement in HIV research.

Simon Mallal, a pathologist and lead author of the study from Murdoch University in Perth, Australia, stated: “These findings may explain why some individuals in these populations have lower viral loads, which slows the replication and transmission of the virus.”

This discovery—from a meta-analysis of nearly 3,900 individuals—could pave the way for developing new antiviral drugs, as previously identified genetic variants have done in the past.

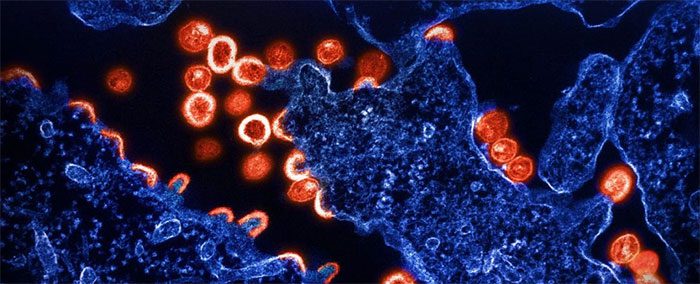

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that destroys CD4 cells (immune cells that help fight infections). With proper treatment, patients can live with HIV for years, even decades, without progressing to AIDS. A patient is diagnosed with AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome) only when they develop opportunistic infections due to immune system failure, or when their CD4 cell count drops below 200. (Image: Sciencealert).

Today, HIV affects approximately 39 million people worldwide, although it is clear that the virus does not impact everyone in the same way. In addition to the genetic mutation in a gene called CCR5, other known genetic variants are believed to confer some resistance to HIV; however, these results have not been clearly established.

Moreover, previous genetic studies have primarily been conducted in people of European descent, while most initial HIV infections have occurred in Africa, where the disease heavily affects individuals of African descent.

In 2021, new genetic variants were discovered in Botswana, but it appears that the variants identified at that time may have made individuals more susceptible to HIV infection or accelerated disease progression.

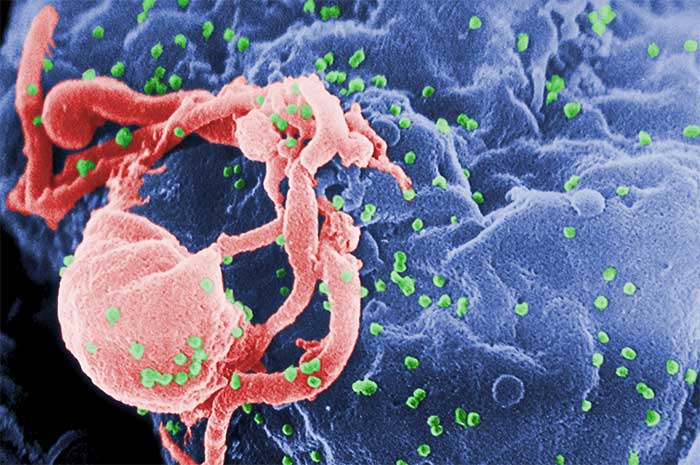

You cannot contract or transmit HIV through hugging, sharing towels, or glasses. However, some individuals may show no signs of HIV for many years after infection, while others may exhibit symptoms within 10 days to several weeks post-infection. (Image: Sciencealert)

In this new study involving Africans living with HIV-1—the most common type of the virus—researchers discovered the opposite: a set of 16 genetic variants appears to limit HIV replication.

The variants cluster around a gene on chromosome 1 called CHD1L. A specific genetic variant topped the list of variants associated with lower viral levels during the chronic infection stage.

This is good news because this level, known as the viral load set point, is an indicator of transmission risk and disease progression in individuals with chronic HIV infection.

“By studying a large population of African descent, we were able to identify a new genetic variant that exists only in this population and is associated with lower HIV viral loads,” said Paul McLaren, a research scientist at Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory for HIV genetics.

McLaren and colleagues estimate that between 4 to 13 percent of individuals of African descent carry this variant.

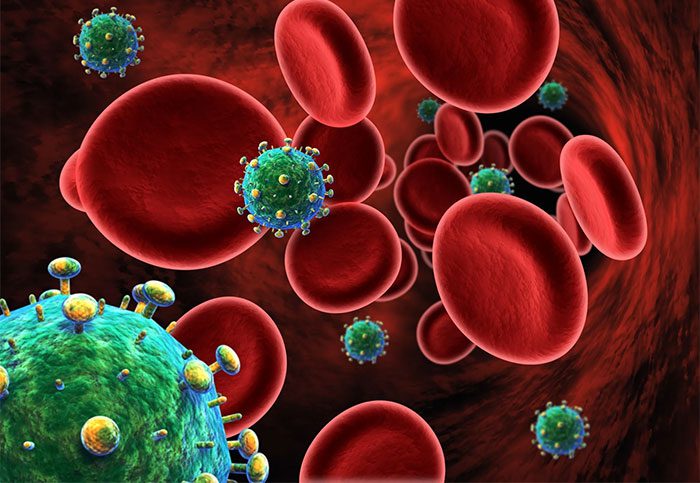

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the rate of HIV transmission from an infected pregnant mother to her child can be as high as 45% if the mother is not treated with antiretroviral (ARV) medication. HIV can be transmitted from mother to child as early as the eighth week of pregnancy through the placenta. The virus can also be transmitted through blood, during labor, or through breastfeeding. (Image: Sciencealert).

While researchers do not yet understand how CHD1L controls viral load, they are eager to learn more as it could lead to new treatment options.

Virologist Harriet Groom from the University of Cambridge stated: “Every time we discover something new about HIV control, we learn something new about the virus and something new about the cells involved.“

Looking further into the research, scientists found that HIV replication increased if CHD1L was turned off in macrophages, a well-known reservoir for HIV-1. However, this did not have the same effect on T cells, another type of immune cell where HIV often replicates.

Despite this promising discovery, researchers are aware that the HIV resistance of the gene is likely related to the complex interaction between two or more genetic variants rather than a single aberration.

It remains unclear how many genetic factors contribute to variations in HIV infection cases.

Due to a weakened immune system, individuals living with HIV can easily contract other infections such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, candidiasis, cytomegalovirus, and toxoplasmosis… (Image: Sciencealert).

Systemic and social factors, such as racial inequality and access to treatment, also influence which groups are more likely to be diagnosed with HIV. At this point, we still need more research to answer questions such as how quickly HIV progresses to AIDS or whether the virus can be controlled to a level below which it can be transmitted to others.

This study has been published in the journal Nature.