The quantum world is indeed a strange realm where nothing is impossible.

One of the most classic scenes in the film Tenet (2020) directed by Christopher Nolan features the Protagonist holding a gun without any bullets, aiming at a concrete target.

Scientist Barbara then gives him a hint: “You don’t shoot the bullet. You catch it.” At the moment the Protagonist pulls the trigger, the bullet suddenly flies backward from the target, returning to the gun and fitting perfectly into the previously empty chamber.

This scene encapsulates Christopher Nolan’s idea in Tenet, that we can reverse the arrow of time, bringing certain objects, or even people, backward into the past. (Illustrative image).

The mechanism known as “Time inversion” can resolve a series of traditional time travel paradoxes, notably the grandfather paradox, where a person travels back in time to kill their grandfather, thereby negating their own existence.

But can time actually be inverted?

In a recent experiment conducted at the University of Toronto, Canada, scientists observed a phenomenon similar to that in Tenet when they shot a photon through a super-cold rubidium atomic cloud; the photon seemed to exit the cloud before entering it.

“Our experiment showed that photons can make atoms appear to spend a negative amount of time in an excited state,” said Professor Aephraim Steinberg, a physicist and founding member of the Quantum Information and Quantum Control Center at the University of Toronto.

Theoretically, Steinberg and his colleagues have demonstrated that time can be a negative quantity.

In research published on the peer-review preprint platform arXiv.org, Professor Steinberg mentioned that he has been contemplating this experiment since 2017. At that time, Steinberg and Josiah Sinclair, a PhD student working in the same lab, were interested in the interaction between light and matter, specifically a phenomenon known as atomic excitation.

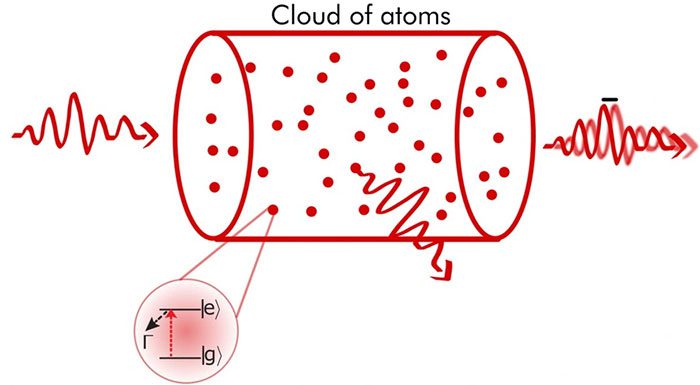

This phenomenon occurs when photons pass through a medium and are absorbed, causing electrons around the atoms in that medium to jump to higher energy levels. When these excited electrons return to their original states, they release the absorbed energy in the form of re-emitted photons, resulting in an observable time delay as light traverses the medium.

Sinclair’s team wanted to measure that time delay and determine whether it depended on the fate of the photon: Could it be scattered and absorbed in the atomic cloud, or could it pass through without any interactions?

“At that time, we weren’t sure what the answer was, and we felt that a fundamental question about such a basic thing should have an easy answer,” Sinclair said. “But the more we talked to other scientists, the more we realized there was no consensus; everyone could only make guesses based on their own intuition.”

Shooting a photon into an atomic cloud, intuitively, the photon should enter and then exit.

Thus, Sinclair and Professor Steinberg spent three years planning and developing an apparatus to test this question in the lab. Their experiments involved shooting photons through a super-cold rubidium atomic cloud and measuring the degree of atomic excitation that occurred.

Two surprising results emerged from the experiment: Sometimes the photons passed through without any interactions, yet the rubidium atoms remained excited—and for a length of time as if they had absorbed those photons.

Even stranger, when the photons were absorbed, they appeared to be re-emitted almost instantly, before the rubidium atoms returned to their ground state—as if the photons, on average, were escaping the atomic cloud faster than expected.

The team then collaborated with Howard Wiseman, a theoretical and quantum physicist at Griffith University in Australia, to provide an explanation. The trio proposed a theoretical framework suggesting that the phenomenon could only be explained by a time quantity having a negative value.

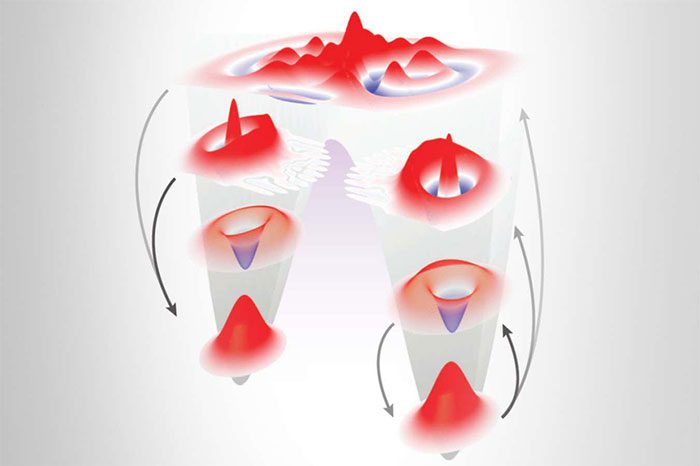

To understand this, one must think of photons in terms of their quantum nature rather than as particles. As the Heisenberg uncertainty principle indicates, you cannot simultaneously measure both the position and momentum of a particle with absolute precision.

This means that the absorption and re-emission of any photon through an atomic cloud does not guarantee to occur within a fixed time period. Instead, it happens over a probabilistic time range.

The experiment shows that sometimes a photon exited the cloud before entering it.

<pThus, when you shoot a photon into an atomic cloud, sometimes, the probability of the photon exiting that cloud at a given moment is higher than the probability of it entering the cloud at that same moment. This leads to a negative time value.

“We were completely surprised by this prediction,” Sinclair said. “A negative time delay may seem paradoxical, but it means that if you were to build a ‘quantum’ clock to measure the amount of time atoms spend in an excited state, the hands of the clock in some cases would move backward instead of forward.”

The findings of the research team at the University of Toronto came just two months after a group at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the United States and the University of Colorado Boulder created the most advanced atomic clock to date.

Its operating mechanism aligns with the very principle that Sinclair and Professor Steinberg are investigating: They use ultraviolet light to excite the nuclei of a thorium-229 atom in a solid crystal.

They then measure the frequency of the energy pulses affecting the nucleus—equivalent to the pendulum in a conventional clock—and count the wavelengths in the UV light using a tool called an optical frequency comb.

Based on this principle, the atomic clock can achieve exceptional accuracy, deviating by only 1 second over 30 billion years—twice the age of the universe and six times the age of the Earth.

Professor Aephraim Steinberg, physicist and founding member of the Quantum Information and Quantum Control Center at the University of Toronto.

However, with this new discovery, the accuracy of this clock becomes a question mark. At some moment, could it potentially run backward? And how might this affect the arrow of time that we typically assume moves in one direction?

More research will be needed to answer these questions. For now, we are akin to a photon in a cloud, uncertain like Heisenberg’s principle suggests. All of this demonstrates that the quantum world is indeed a strange realm, where seemingly nothing is impossible.